Reading time: 7 minutes

Treason doth never prosper; what’s the reason?

For if it prosper, none dare call it Treason. John Harington

Levying war against the Crown was one of the key treasonable offences defined by the 1352 Treason Act. Yet, during the civil wars of the 1640s and again in the American Revolutionary War of the 1770s and 80s, those that levied war against the monarch not only avoided punishments for treason, but rejected royal authority and accused their kings of levying war – of committing treason – against the state.

By Daniel Gosling, The National Archives

On 30 January 1649, this resulted in the execution of King Charles I for ‘levying war against the said Parliament and People’, on 4 July 1776, the thirteen United States of America declared themselves independent from King George III, who had established ‘an absolute Tyranny over these States’. Thereafter, treason laws protected these republican states, not the monarch.

In this, the first of two blogs, we’ll examine how Charles I’s executioners used the language of treason to prosecute the king, and how treason laws were subsequently used during the Commonwealth period (1649-1660).

Against the kingdom

In the medieval period, monarchs would often use Parliament to denounce their predecessors, alleging that they had committed treasonous acts. One of Henry VII’s first moves, following his victory over Richard III at the battle of Bosworth in 1485, was to pass an act of attainder through Parliament declaring that Richard and his supporters had ‘traitorously levied war’ against the new – legitimate – king, Henry VII.

However, the trial of Charles I in January 1649 was the first time that Parliament – specifically the Commons – had acted against a reigning monarch without the backing of a rival claimant to the throne. The Parliamentary army had emerged victorious over Charles’ Royalist forces during the civil wars of the 1640s, in which several thousand civilians were estimated to have died. As the head of the defeated party, the king was therefore blamed for such bloodshed, and the Commons moved to punish Charles for these crimes.

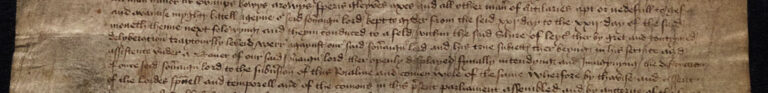

They were acting without precedent, and so the Commons continually stressed that they had the authority to try traitors, and that even the king could commit treason, not against himself but against the kingdom. On 1 January 1649, the Commons declared that ‘by the fundamental Laws of the Kingdom, it is treason in the King of England, for the Time being, to levy War against the Parliament and Kingdom of England’.

Three days later, they reinforced this authority, declaring that ‘the Commons of England, in Parliament assembled, being chosen by, and representing the People, have the Supreme Power in this Nation’. On this authority, they established the High Court of Justice, specifically for the purpose of trying the king. Throughout his trial, however, Charles I refused to acknowledge the authority of this High Court of Justice to try him.

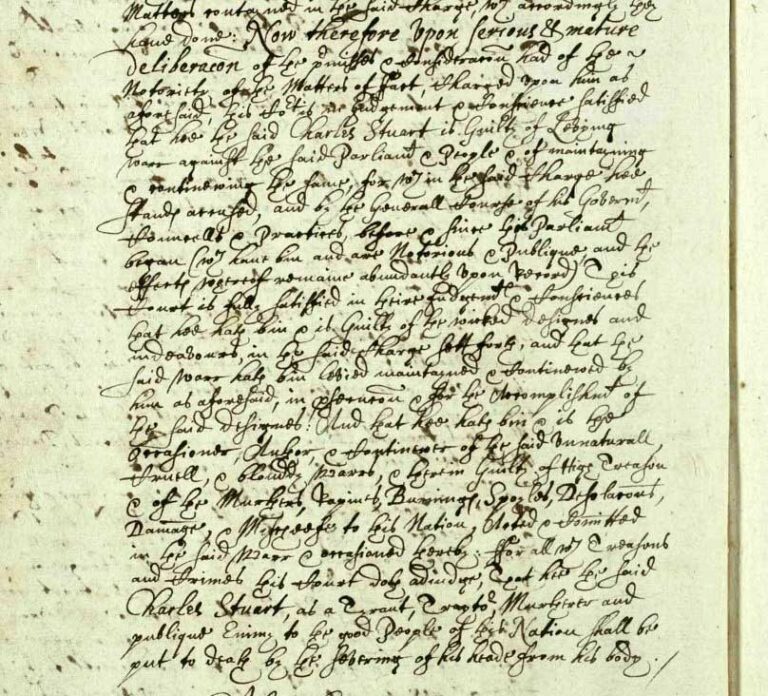

On the afternoon of 23 January, therefore, chief prosecutor John Cook warned the king that if he continued to refuse to answer the charges laid against him, then the court would proceed to sentencing. Charles remained resolute, and was sentenced on 27 January 1649. For raising the standard against and causing the bloodshed of his subjects during the civil wars of the 1640s, Charles was found ‘guilty of High Treason and of the murders, rapines, burnings, spoils, defilations, damages, and mischiefs to this nation’.

Three days later, on 30 January, Charles I was executed outside of Banqueting House at Westminster, ‘put to death by the severing of his head from his body’. Treason was now definitively a crime against the state.

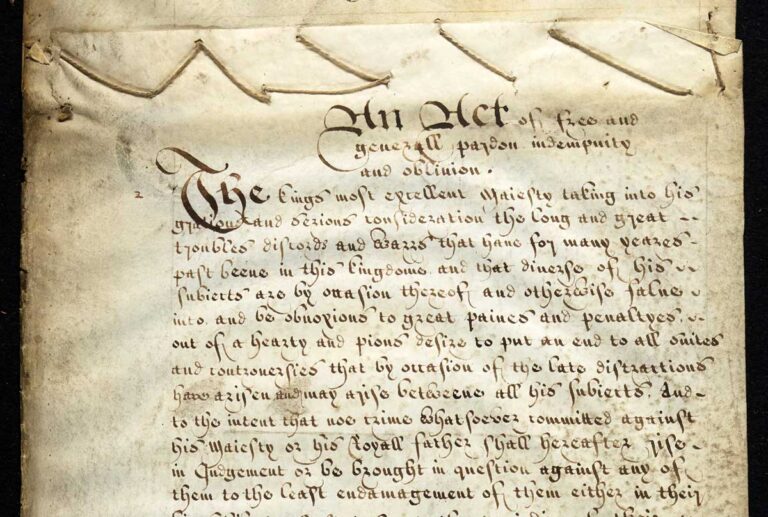

Indemnity and oblivion

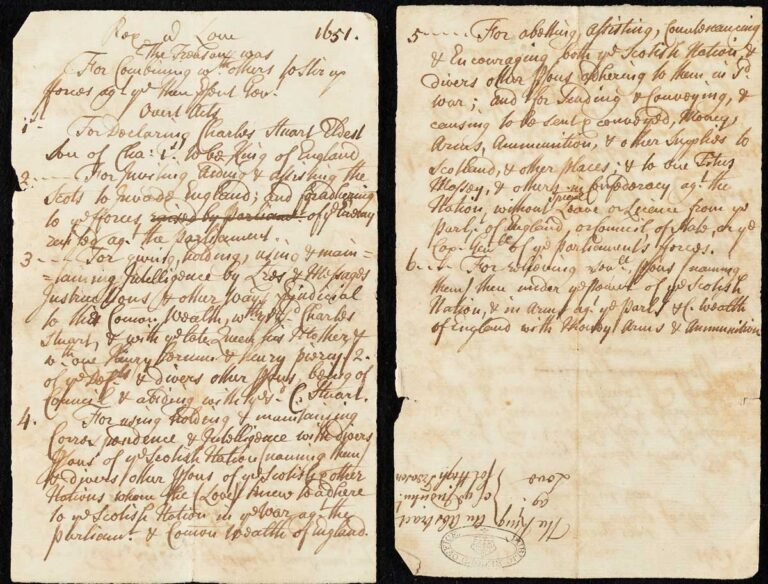

Despite executing their king, undoubtedly an act of treason, those responsible for this historic act were not initially tried as traitors. They had successfully argued that Charles was the traitor, and made moves to further legitimise their right to rule by enacting new treason legislation that protected them. This new legislation reinforced that it was treason to levy war against the state or to adhere to its enemies. It also made it a treasonable act to declare that Charles Stuart, the eldest son of Charles I (and the future Charles II), was the rightful king of England.

But, treason laws only protected those responsible for the execution of Charles I so long as they remained in power. In 1660, with the return of the monarchy under Charles II, they had good reason to fear that the new king would punish them for the treasonous acts they committed against his father, Charles I.

In the 1660 Indemnity and Oblivion Act, Charles II pardoned most people that had committed crimes during the civil wars and the Commonwealth period. However, those men involved in the killing of Charles I were not included in this pardon, and instead were to be hunted down and tried for treason.

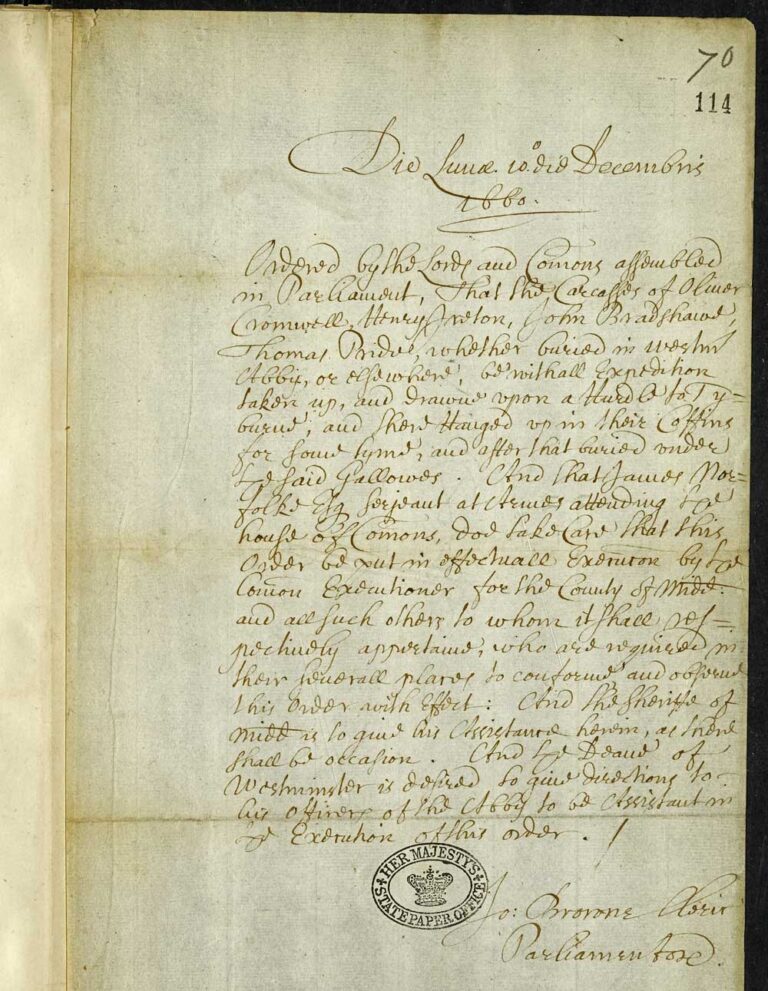

Even death could not save these regicides. The bodies of four men who had already perished – Oliver Cromwell, John Bradshaw, Henry Ireton, and Thomas Pride – were exhumed so that they could be ritually executed for treason. Their corpses were hanged in chains at Tyburn, then their heads were removed and placed on spikes above Westminster Hall. Finally, their bodies were thrown into a common grave beneath the gallows.

A precedent set

Treason laws, then, only protected you for as long as you held authority within the realm. Though the regicides of Charles I ultimately fell afoul of these laws, they had set an important precedent that monarchs could be held accountable for crimes against their people.

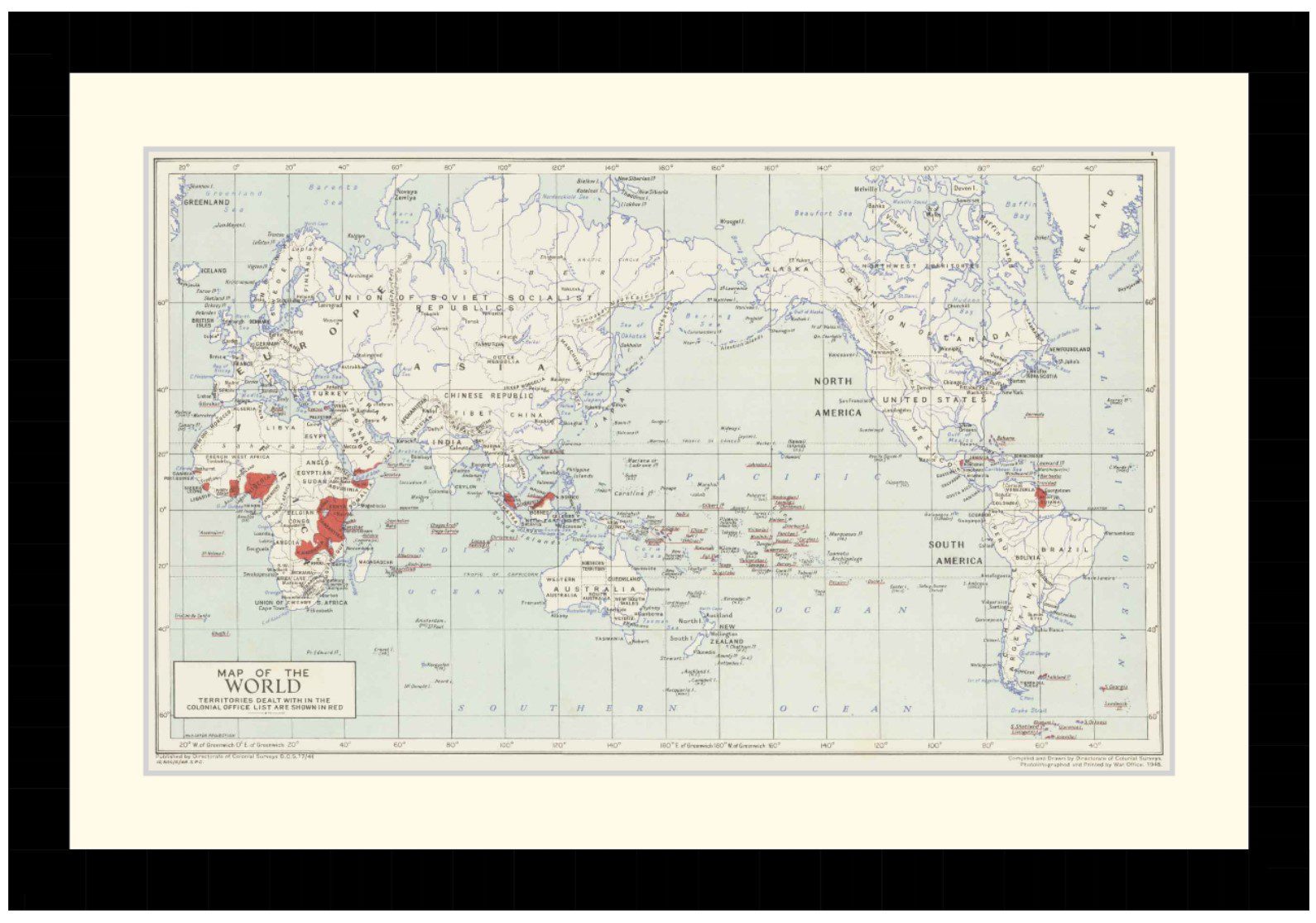

A century later, during the American Revolutionary Wars, an English – now British – monarch would once again be accused of committing treasonous acts against their subjects. The alleged crimes of George III against his American subjects will be the topic of the final part of this two-blog series.

This article was originally published in The National Archives.

Podcasts about treason against the Crown

Articles you may also like

Captain Cook: The Aboriginal Perspective – New Podcast

Captain Cook has been celebrated, wrongly, as the first European to discover Australia but many now believe it is time to reappraise his legacy particularly in light of the devastating effect it had on the native Aboriginal people of Australia. Professor John Maynard is a Worimi man and Director of Aboriginal History at The Wollotuka […]

General History Quiz 47

The History Guild Weekly History Quiz.See how your history knowledge stacks up. Have an idea for a question? Submit it here and we’ll include it in a future quiz! If you would like an invite to future history quizzes please enter your details below. Subscribe * indicates required Email Address * First Name Last Name […]

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.