Reading time: 6 minutes

This is the second part of a two-blog series exploring treason against the state, as used during the civil wars of the 1640s and again in the American Revolutionary War of the 1770s and 80s. Previously, treason laws had always protected the life and authority of the monarch. Now, they were used by those that levied war against the monarch to reject royal authority and accuse their kings of levying war – of committing treason – against the state.

In our first blog, the execution of Charles I was framed in the context of his crimes against the state for ‘levying war against the said Parliament and People’. In this final part, we’ll examine how and why America declared independence from Great Britain, and where treason fits into this story.

Treason doth never prosper; what’s the reason?

For if it prosper, none dare call it Treason.John Harington (1561–1612)

Treason on both sides?

The execution of Charles I for treason against his people in January 1649 created the historic precedent that monarchs could be held accountable for their (alleged) crimes. In the 1770s, this theory that kings could commit – and be punished for – treasonable actions was tested once again.

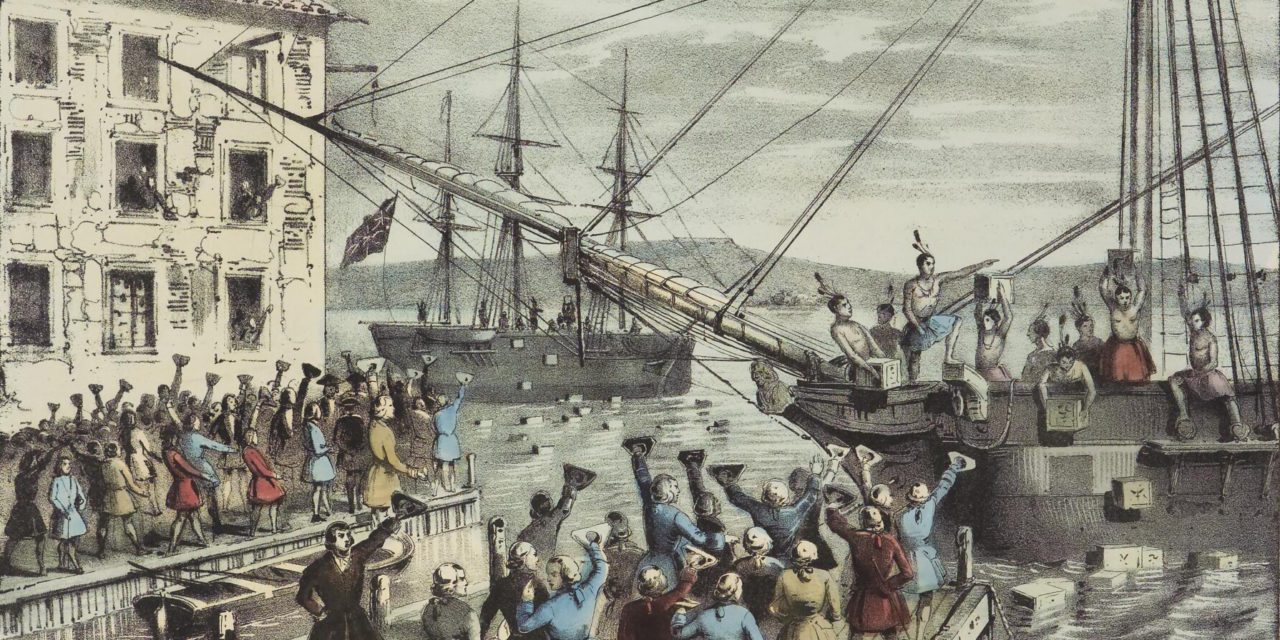

This time, it was King George III accused of levying war against his subjects in the British colonies in North America. The people of these American colonies had become increasingly frustrated throughout the 1760s and 1770s by the British Parliament trying to levy taxes against them, despite these colonies not having any representation in Parliament. These frustrations resulted in many acts of protest, including the Boston Tea Party of December 1773, when an entire shipment of tea sent by the East India Company was dumped into Boston harbour, protesting the 1773 Tea Act.

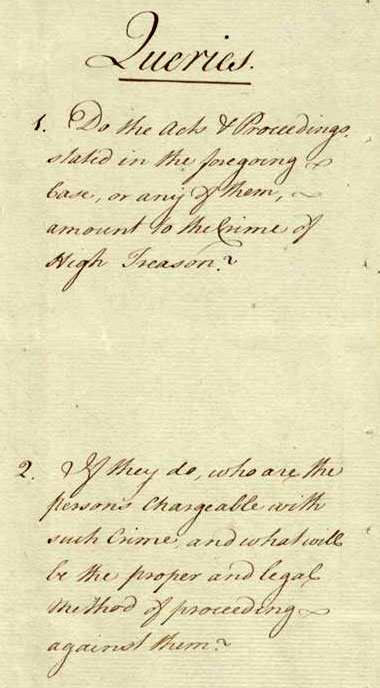

The British authorities in America were unsure how to prosecute these protestors and asked the Attorney General in England for advice. He responded that these protests constituted high treason as they undermined the state of Great Britain by contravening a British act of Parliament. However, these authorities found it difficult to prosecute the offending parties, as there was little appetite in America to punish those protesting such controversial taxes.

In March 1774, Parliament ordered that the port of Boston be closed until such time as they paid for the tea destroyed the previous December. This only exacerbated tensions across the thirteen colonies in America, who supported their sister state of Massachusetts and imposed a boycott on British imports.

Refusing to back down, George III declared the state to be in open rebellion in February 1775, and authorised the use of force to restore British rule. Armed hostilities broke out in April at the battles of Lexington and Concord. Like Charles I before him, George III was now at war with his own subjects.

‘Rebellion’ or a traitorous king?

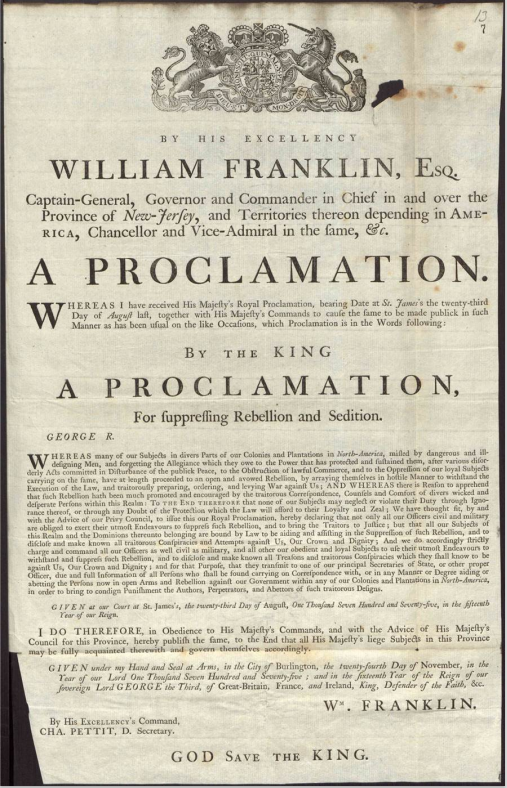

In August 1775, George III issued the Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition, declaring the American colonies to be in a state of ‘open and avowed rebellion’. Part of the proclamation urged loyal subjects in America to ‘disclose and make known all treasons and traitorous conspiracies’. A definite statement by the King of Great Britain that the American rebels had committed treason against their king.

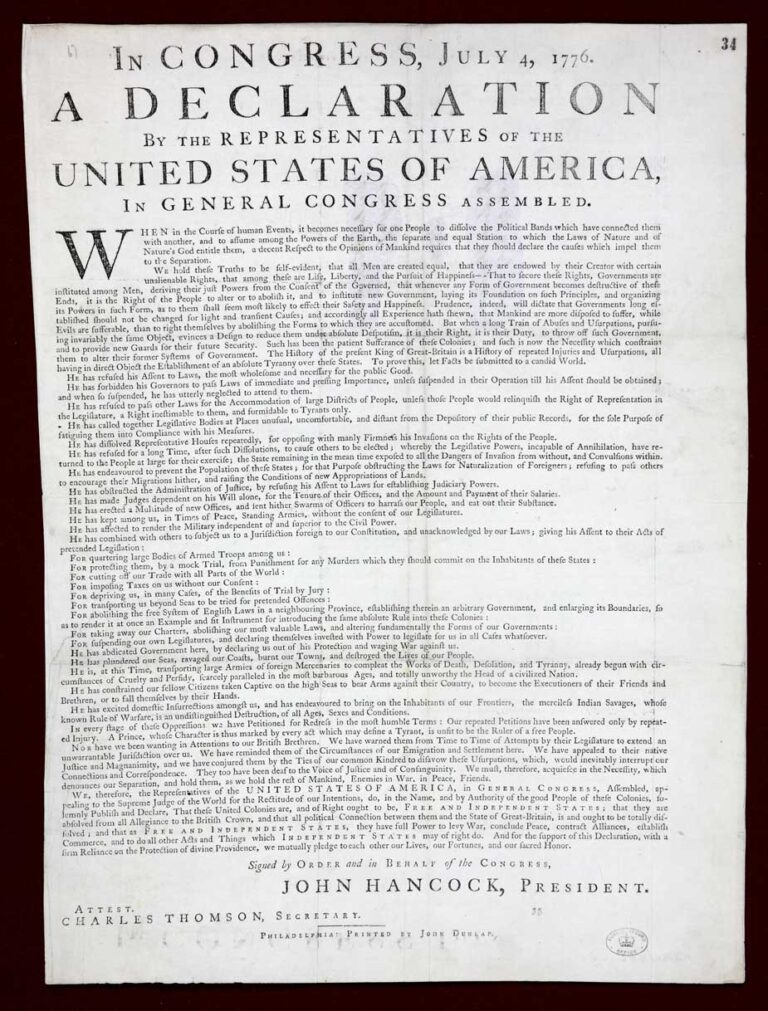

But the American people didn’t see it that way. To them, it was King George that had levied war against his subjects in the American colonies. Their declaration of independence, signed on 4 July 1776, formally denounced the authority of the British monarch in the American colonies, in response to George III’s treasonous and tyrannical actions.

The US Declaration of Independence

Much of the US Declaration of Independence is a list of complaints about King George’s abuses. As with the sentencing of Charles I a century earlier, it was designed to demonstrate how the king was unfit to rule:

The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.The US Declaration of Independence, 1776.

Specific abuses echoed the charges laid against Charles I in 1649. In the declaration, King George was denounced as having ‘plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people’; Charles I had been found ‘guilty of High Treason and of the murders, rapines, burnings, spoils, defilations, damages, and mischiefs to this nation’.

The American people thus used George III’s alleged abuses to declare themselves free from the ‘tyranny’ of Great Britain, free ‘to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do’.

Treason against the United States

Like the Commons of the 1640s before them, the newly independent United States of America utilised the language of treason to condemn their king for his crimes against the state. Similarly, following their separation from King George III, treason laws now protected the republican state. The treason clause of the US Constitution, created in September 1787, is the only criminal law in the US founding document. As with the treason laws of the English Commonwealth in the 1650s, treason in the US Constitution drew on the 1352 Treason Act for inspiration, declaring that ‘Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort’.

However, unlike in England, kings were never invited back to rule America, meaning that their acts of treason – of levying war against their king – are instead remembered as positive acts of revolution and liberation, whereas the actions of George III are remembered as traitorous to the American people. Those that executed Charles I, on the other hand, have gone down in history as regicides. Just as history is written by the victors, so too is treason a matter of perspective.

This article was originally published in The National Archives.

Podcasts about treason during the American War of Independence:

Articles you may also like:

Women of America – AudioBook

WOMEN OF AMERICA – AUDIOBOOK By John Ruse Larus (1858 – 1920) The present volume completes the story of woman as told in the series of which it forms part. The history of nations is, in its ultimate analysis, largely that of woman. Therefore this series in its wide inclusiveness forms a more than ordinarily interesting […]

Remembering Long Tan: Australian army operations in South Vietnam 1966–1971

Reading time: 5 minutes

The anniversary of Long Tan reminds most Australians that despite winning that iconic high intensity battle, the Australians and New Zealanders lost the Vietnam War. In fact, the First Australian Task Force (1ATF) fought at least 16 big battles, and through superior firepower from artillery, armor and airpower, won them all, sometimes by a narrow margin.

But most of the struggle in Phuoc Tuy province and South Vietnam was a prolonged low intensity guerrilla war. The big battles only mattered if the US and her allies had lost them, as big battle success allowed the allies to stay in the War. Enemy defeats just forced the enemy to revert to low intensity guerrilla war, which the allies had to control if they were to win.

Why we should remember the Battle of the Coral Sea

The Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942 has become the touchstone for the Australian-American strategic relationship. The 75th anniversary provides an opportunity to reflect on why this engagement, in which for the first time the opposing fleets did not sight one another, still resonates. By Peter Jones During the six months after the […]

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.