Reading time: 6 minutes

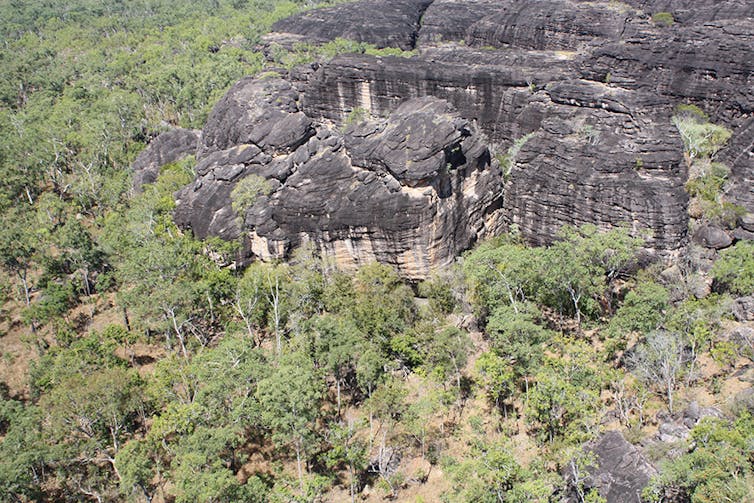

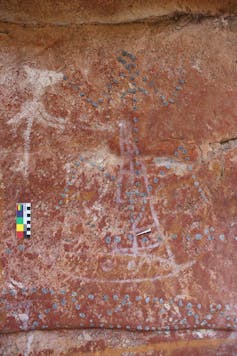

The rock art of northwestern Arnhem Land is world-renowned and represents one of the world’s most enduring artistic cultures. Rock art is a continuing tradition. It includes images of “outsiders”: people and objects brought to Australian shores by Macassans from southeast Asia and, later, by Europeans.

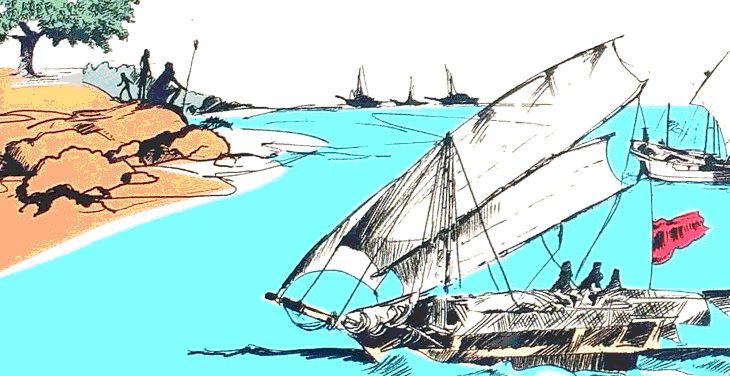

Paintings of sailing vessels, smoking pipes, firearms, domesticated animals and other exotic items dot the landscape in Arnhem Land, often overlaying earlier works. Comparatively recent paintings feature more common images too, such as kangaroos, emus, and hand stencils.

While most Australians know about the history of European arrivals, few are familiar with the ongoing visits by people from southeast Asia to the region. Our latest research shows artists depicted early trading sailing vessels less often and differently to European ships — suggesting they viewed these encounters with other cultures in contrasting ways.

By Sally K. May, Daryl Wesley, Joakim Goldhahn, Paul S.C.Taçon, University of Western Australia, Griffith University and Flinders University

Visitors to our shores

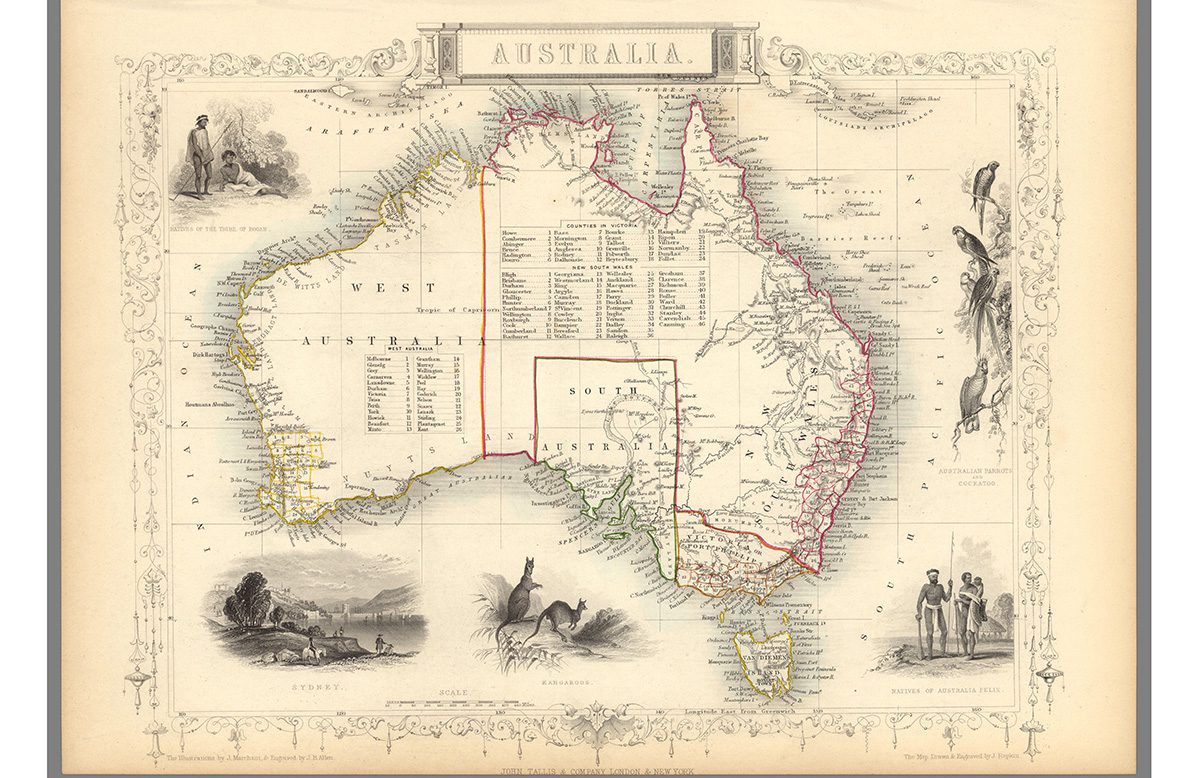

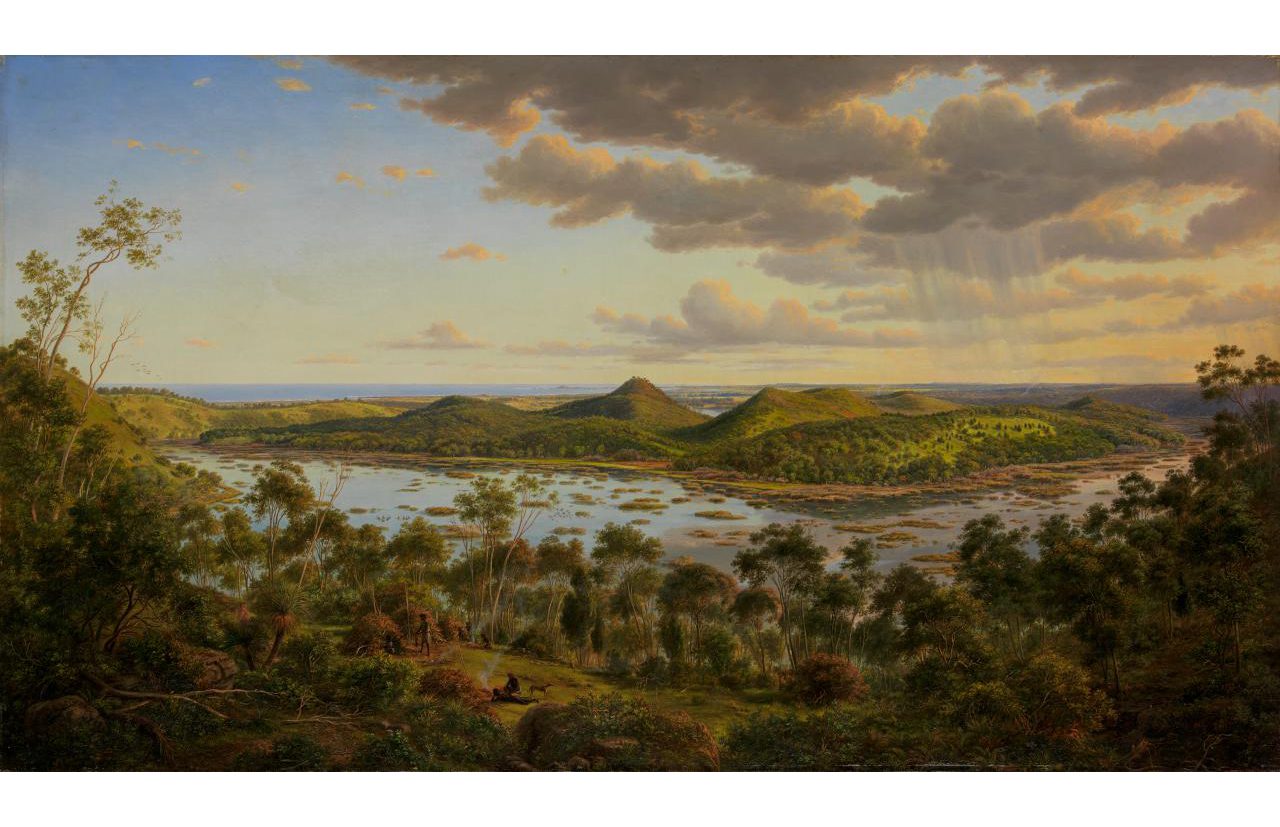

Far from the generally accepted notion of an isolated shoreline, the north Australian coast was teeming with sailing vessels engaged in trade for hundreds of years before European exploration and settlement.

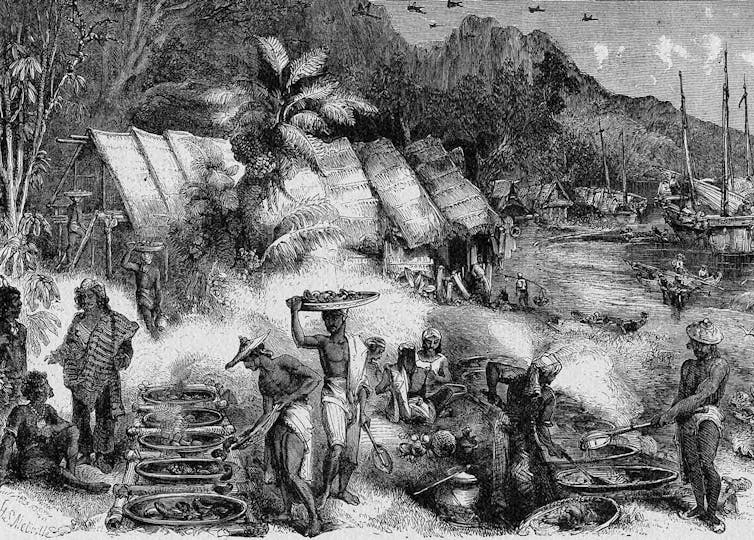

Most commonly referred to as Macassans (because they’d made the crossing from the port of Makassar in southern Sulawesi) these early traders came in fleets of praus with their signature tripod masts, to harvest trepang (sea cucumber) and for materials such as turtle shell, beeswax, and iron wood.

Working with Aboriginal Traditional Owners, especially members of the Lamilami family, our new research focuses on the Namunidjbuk clan estate within the Wellington Range in the Northern Territory. We looked closely at one particular type of rock art — boats in the form of Macassan praus and European ships.

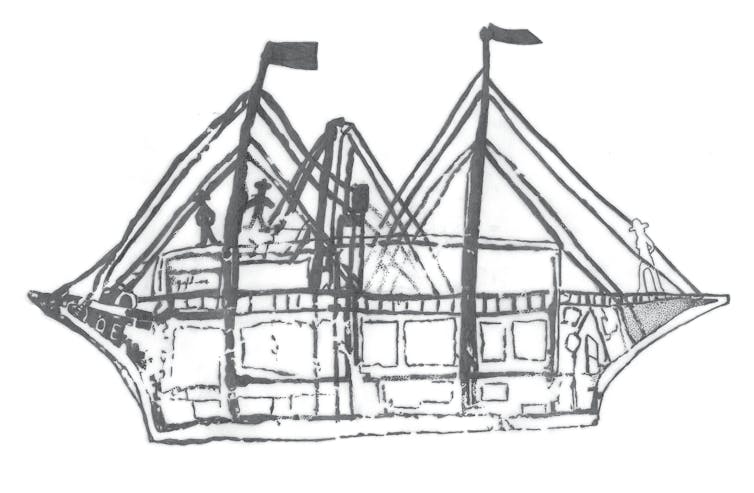

Sailing vessels are among the most common new subjects in rock art made during the last 500 years in northwest Arnhem Land. Yet, there is a perplexing inconsistency in how Aboriginal artists of this region treated Macassan prau and European ships.

The earliest dated prau depiction is from the first half of the 1600s. No depictions of European ships are thought to be older than the early 1800s.

Yet we counted many more rock art images of European ships: 50 examples in the study area, compared to only six prau (five images feature elements of both).

These extraordinary works illustrate the maritime history of this region. They range in detail from basic outlines of hulls to detailed depictions of European ships. Some even illustrate cargo.

Others reveal ship features found under the waterline such as anchors and propellers. Southeast Asian prau are recognisable because of their unique tripod masts and sails. Some paintings of European ships show the crew smoking pipes and with their hands on their hips.

The missing Macassans

When people are portrayed on or next to watercraft in our study area, it is always in association with European ships, with no depictions associated with prau at all.

So, why did Aboriginal artists feel the need to paint so many European ships, and sometimes their crew — but very few relating to southeast Asian visits?

We argue the proliferation of European-related imagery signals the threat they posed to Indigenous sovereignty. Communicating this threat (via rock art and other means) to family and neighbouring clans was an essential tool for inter-generational education, inter-clan communication, resistance and survival.

The lack of praus does not suggest a lesser cross-cultural relationship between Macassans and Aboriginal people. In fact, nearby in Anuru Bay is one of the largest Macassan trepang processing complexes in the NT.

But visits by the Macassans were seasonal, while the Europeans came to stay. Cross-cultural contact between Aboriginal people and Macassans in this region is generally thought to be characterised by mutual respect and exchange. Contact with Europeans was more violent, with historically known killings and massacres of Aboriginal people.

Importantly, our findings in northwest Arnhem Land are the opposite of research undertaken in other parts of northern Australia, such as Groote Eylandt, where there are many depictions of Macassan prau and crew. This reminds us that one size does not fit all in the history of invasion and cross-cultural contact in northern Australia.

For decades R. Lamilami (1957-2021) worked to protect his Country and to educate outsiders on the cultural significance of the Namunidjbuk clan estate and, more broadly, the Wellington Range. With this article we pay tribute to his life’s work and his firm belief that rock art is an irreplaceable history book for Australia.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.