Reading time: 5 minutes

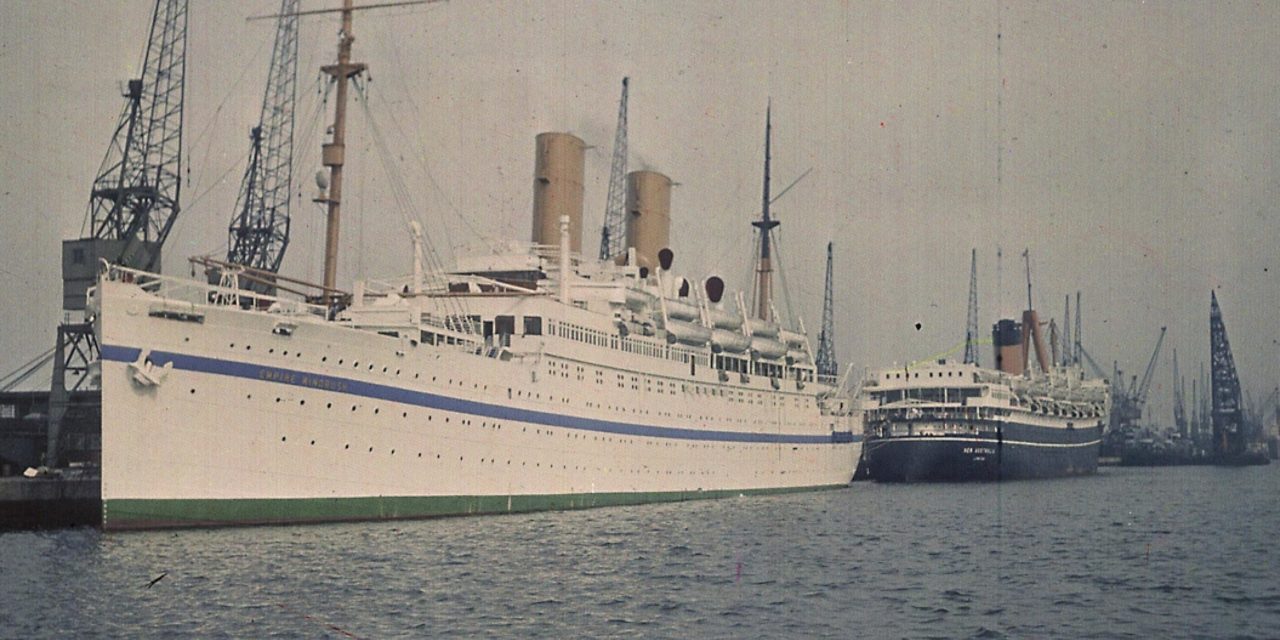

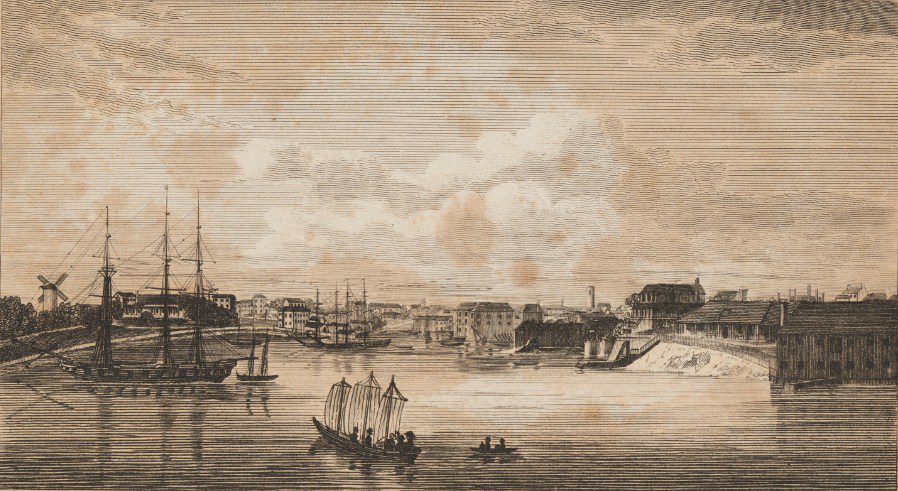

Next June will mark the 75th anniversary of the arrival of HMT Empire Windrush at Tilbury Harbour, carrying on board some 800 passengers who gave their last country of residence as somewhere in the West Indies, and many of whom would migrate as workers and would settle in Britain and help steer its economic recovery after the Second World War. But this was only one journey in the vessel’s history and this article examines its colourful, chequered, and varied life since its maiden voyage was made in 1931 to its sinking in 1954.

By Roger Kershaw.

Empire Windrush actually started its life as a German vessel called Monte Rosa in December 1930. It was the last of five Monte-class passenger ships built between 1924 and 1930 and operated by the Hamburg Sud Shipping Company. The Monte class ships were all named after mountains in Germany and South America, Monte Rosa being the second highest mountain in the Alps. All five ships were originally intended as emigrant ships sailing to and from Germany and South America but in reality two became German cruise ships, enjoying great success in the 1920s. By 1931 when Monte Rosa was put into service, the cruise industry was struggling after the advent of the Great Depression so for its early years, Monte Rosa became an emigrant ship.

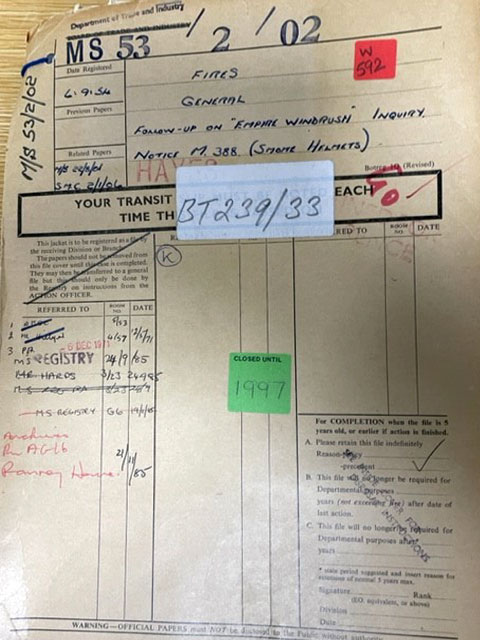

On the outbreak of the Second World War she was converted as a troop ship and deployed for the invasion of Norway in 1940. She was also used for the deportation of nearly fifty Norwegian Jewish people in 1942, the majority of whom would perish in the Nazi concentration camps. In March 1944 she was attacked by the RAF – sustaining at least one torpedo – yet she made safe harbour in Denmark. Only three months later she sustained more damage by a mine explosion, damaging her hull, and then another mine explosion in the Baltic damaged her in February 1945. At the end of the war, she was seized as a prize of war by the British forces, and, in February 1947, she was reassigned as a British troopship, registered in the Port of London, under the new name HMT Empire Windrush, with its official number 18156.

On its arrival at Tilbury on 22 June all 1,027 passengers were met with a media frenzy heralding the beginning of the British multiracial society. It continued as a troopship until 30 March 1954 when she sank in the Mediterranean after an explosion and outbreak of fire.

Only two years prior to its loss, its mechanical reliability had been called into question following a series of complaints leading to a lack of confidence by passengers. On two occasions in the early 1950s the ship had been delayed at Singapore to effect mechanical repairs. One the first occasion, there was a delay of eight days to carry out engine repairs and on the second, the ship was found to have a fractured auxiliary compressor valve and connecting rod.

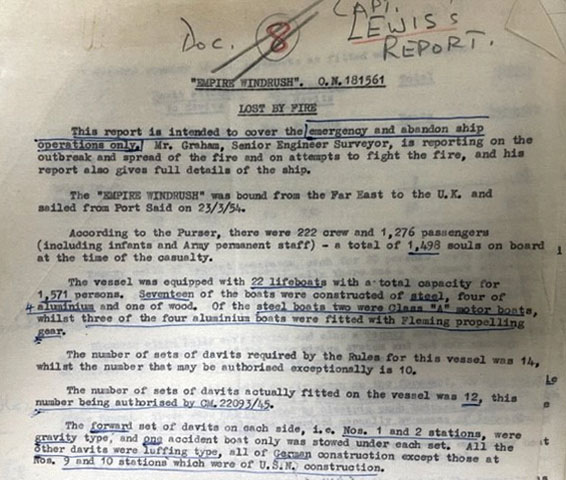

Her last voyage set sail from Yokohama in Japan in February 1954 and was bound for London with stops at Hong Kong, Singapore, Colombo, Aden and Port Said. It took ten weeks to reach Port Said with nearly 1,500 people on board – 222 crew and 1,276 passengers, including military personnel and some women and children. It sailed from Port Said on 23 March equipped with 22 lifeboats with a total capacity for 1,571 persons. On the morning of 28 March at 6.15am there were reports of three heavy thumps from below decks and the lights in the passage went out. Very thick black smoke was seen coming from the after funnel and very soon after as the fire spread, passengers were ordered to the lifeboats and the order to abandon ship was given at 6.45am. According to reports there was no sign of panic at any time. The Master was the last to leave the vessel at 7.35am. Rescue vessels arrived quickly at the scene and picked up all survivors and landed at Algiers. No lives were lost other than four crew who were killed in the engine room by the blast and fire.

The Report of the Court of Inquiry into the loss of the Empire Windrush on 27 July 1954 made three recommendations – significantly increasing the number of smoke helmets provided on board cargo and passenger ships; the regular full examination and inspection of uptakes and funnels in all vessels; and the dispersal of emergency controls and connections.

The Empire Windrush or Monte Rosa was the last surviving Monte-class ships when she sank. The Monte Cervantes sank near Tierra del Fuego in 1930 and the other three were destroyed during operations in the Second World War. Monte Sarmiento and Monte Olivia were both sunk by air raids in Kiel and the Monte Pascoal met a similar fate off the Danish coast in 1945.

Just as her arrival was reported at Tilbury Harbour 16 years earlier, the media reported her last voyage.

This article was originally published in The National Archives.

Podcasts about HMT Empire Windrush:

Articles you may also like:

Australians in the Mediterranean during WW2 eBook

Thousands of Australian soldiers saw combat in a series of battles in the Mediterranean and North Africa. Their service is less well known as it has tended to be overshadowed by the later battles in New Guinea and the Pacific. History Guild has created and published this eBook which tells the stories of the determination, resilience, bravery and sacrifice of the Australians who served in the Mediterranean theatre of the Second World War. It is available as a free download below.

Weekly History Quiz No.232

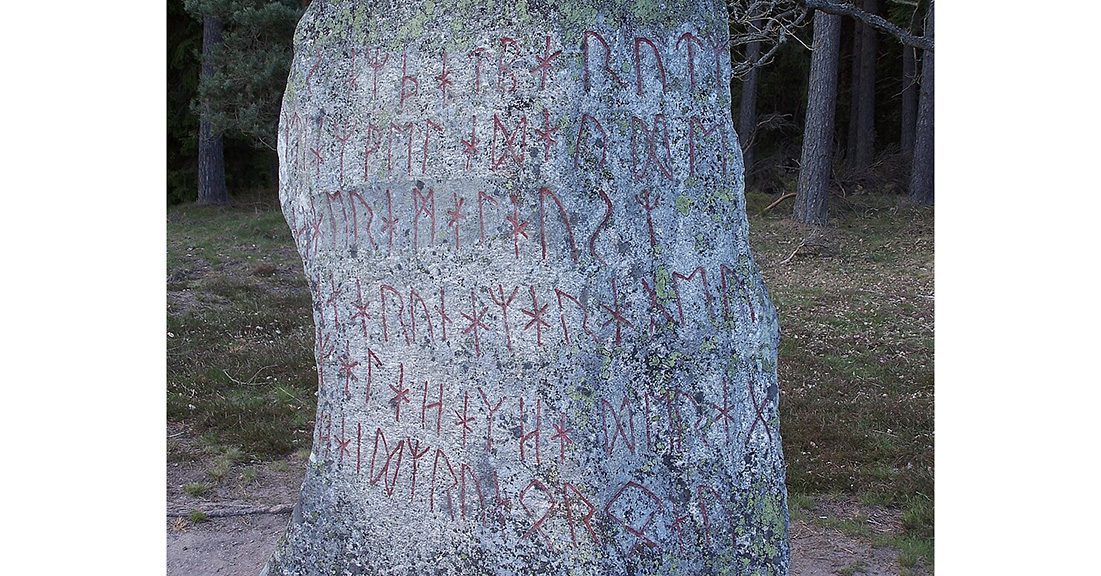

1. Which group developed a form of writing known as runes?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.