Reading time: 6 minutes

Nothing beats a good chase sequence, particularly when an animal is involved. Recently, social media was captivated by two zebras that escaped from a Philadelphia circus. Rest assured, the two rogue performers are now safe, having been captured by local police.

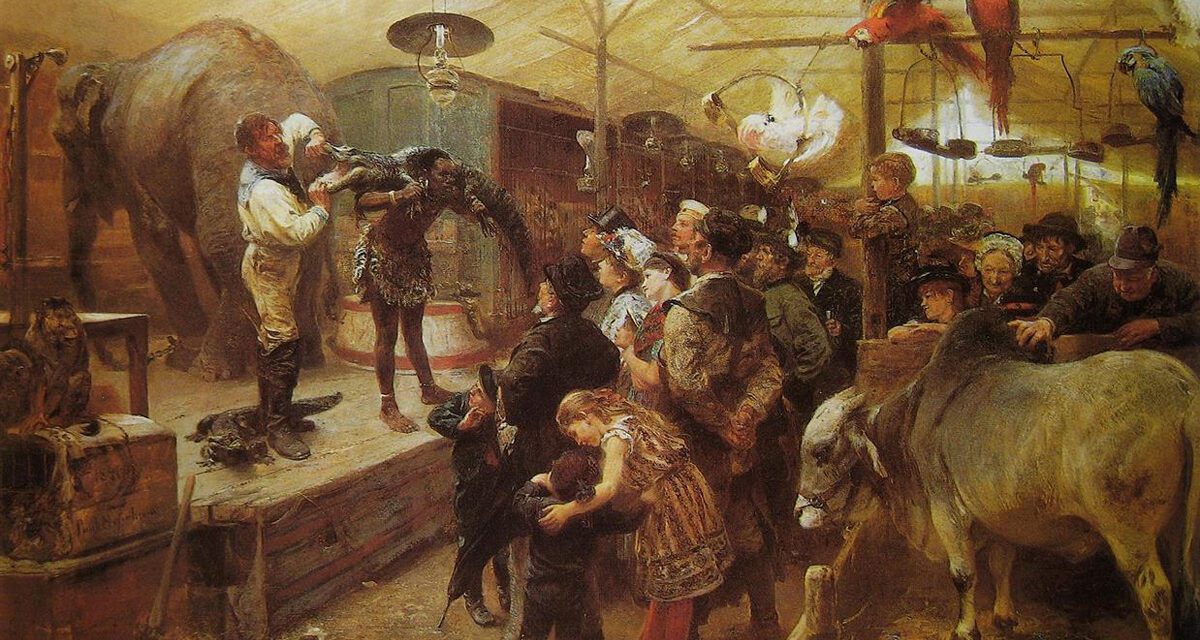

Thankfully, exotic animal escapes are relatively rare today, and usually end reasonably happily. But in the 19th century, when travelling menageries and circuses traversed Britain and the US, such break-outs were far more common. Menageries toured widely from the late 18th century, bringing exotic animals within reach of even the poorest members of society. Health and safety was not a priority for exhibitors, and it wasn’t unheard of to find an orangutan in your bedroom or a tiger loose in the street.

By Helen Cowie, University of York

Just like today, the newspapers of the time jumped on these stories with relish, revelling in the horror of a predator on the prowl. Drawing on these valuable (though not always entirely trustworthy) accounts, here are six of the most notorious animal escapes from the Victorian era.

The ghostly ape

In 1821 “a nocturnal apparition” caused the death of a man in the Rue de Monnaie in Paris. The “apparition” – in reality a “large ape” – had escaped from a neighbouring menagerie. It had “groped” its way along the rooftops and “descended through one of the chimney pots” into the victim’s bedroom, causing the man to die of fright. The story bears an uncanny resemblance to Edgar Allen Poe’s famous detective story, The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841), in which two women are brutally murdered by an escaped orangutan.

The highway tiger

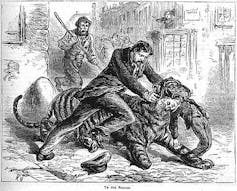

One of the most notorious attacks by a loose wild animal occurred in 1857, when a tigress escaped from a van en route from London’s docks to Charles Jamrach’s exotic animal business on the Ratcliff Highway. As the animal skulked down the road, she was approached by a young boy who unwisely “began patting her”, thinking she was a big dog. The tigress responded by seizing the boy by the shoulders.

She would probably have killed the child had Mr Jamrach not come to his rescue, hitting the beast on the head with a crowbar. Though “frightfully mangled”, the boy eventually recovered from his physical injuries, but continued to show signs of psychological trauma. The Birmingham Daily Post reported that he subsequently conducted himself “in a strange manner” at school and bit his own brother in bed in the belief that he was the tiger.

The Grimsby bear

In 1883, an escaped bear terrorised the inhabitants of Grimsby in Lincolnshire. The animal had broken out of its den in Wombwell’s menagerie by tearing up some loose floor boards. It proceeded to roam the streets of the town, where it was spotted by a local fisherman and reported to the police. A local constable went to assess the situation, but on being confronted with a huge bear he took fright and ran to fetch the menagerie owner.

The bear, now chased by keepers and onlookers, wandered further into the centre of Grimsby, where he mauled a large dog, hopped into the back of a shop and scrambled through a window into the kitchen of a joiner named Mr Rubenstein, who was asleep with his wife upstairs. After a considerable tussle, the animal was driven out through the door and marched back to the menagerie.

The drunken elephant

You’d think it would be difficult to lose an elephant. But that is exactly what happened in Holyhead, Wales, when Batty’s menagerie was visiting the town. One Wednesday evening, after the performance, the menagerie’s elephant was “safely lodged” in a stable close to the George hotel and left for the night. When the keeper returned to the stable the following morning, however, he found “to his great astonishment”, that it had disappeared. A frantic search ensued, but there was no trace of the elephant. In the afternoon it was discovered “lying fast asleep in a wine cellar of the hotel”, surrounded by empty bottles of wine!

The stampeding rhino

Things are always more dramatic in the US, and menagerie accidents were no exception. In 1872, a rhinoceros was being led into the ring at Warner and Co.’s menagerie in Red Bird, Illinois, when it “suddenly threw up its head … and broke loose from the men”. The animal rampaged through the show, trampling one keeper, then goring another “in the stomach, ripping out his bowels and killing him on the spot”.

Still surging with energy, the rhinoceros stampeded towards a row of seats on one side of the tent, breaking the arm of a spectator. It knocked down a pole in the centre of the menagerie, romped around a little museum, and burst into the street outside the show. The rhino finally came to a rest outside a vacant house, where it was apprehended. The damage caused to the circus was estimated at $3,000.

The sewer lion

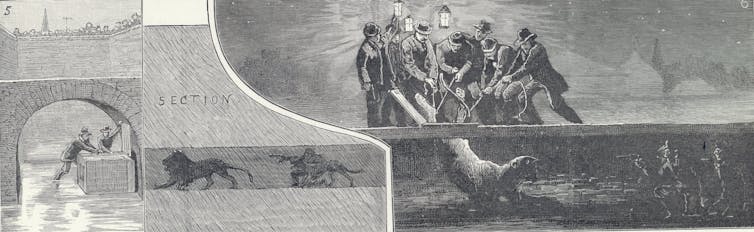

In 1889 a large lion slipped out of its cage and took refuge in Birmingham’s sewers. As news of the escape spread, panic swept through the community, a fear intensified by the fact that “as the lion made his way through the sewers, he stopped at every manhole he came to, and there sent up a succession of roars”. To diffuse the alarm, lion tamer Frank Bostock staged a successful recapture of the lion, and informed the public that the drama was over.

But the following day, he confessed the truth to the authorities and requested 500 policemen to help him catch the loose beast. With policemen stationed at every manhole, Bostock and his men descended into the sewer and hunted down the lion, cornering the animal and securing him with ropes. The Graphic published a dramatic illustration of the escapade, showing a shifty-looking lion emerging from a tent.

This article was originally published in The Conversation

Articles you might also like:

General History Quiz 126

1. What practice did Martin Luther criticise in his Ninety-five Theses?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

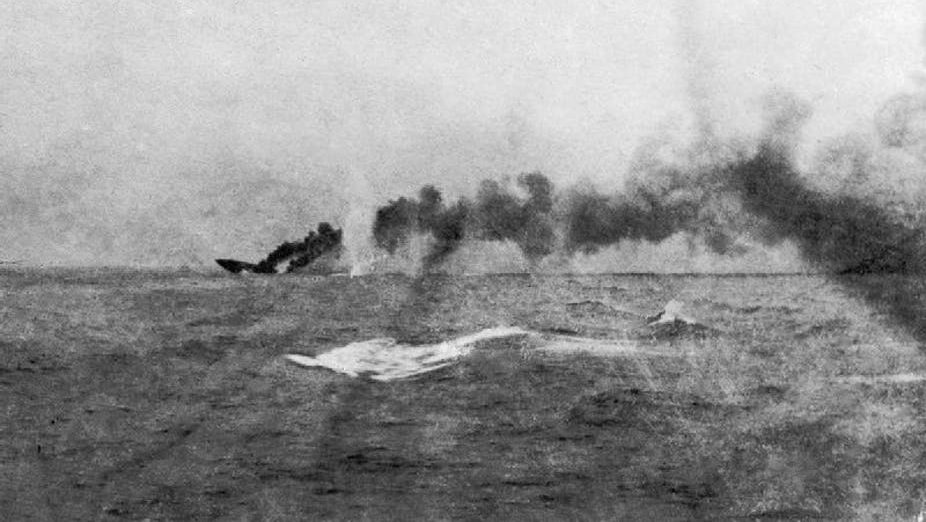

Jutland: Why World War I’s only sea battle was so crucial to Britain’s victory

By Andrew Lambert, King’s College London. Modern understanding of World War I is dominated by the immense human cost of the war on land with its trenches, artillery and machine guns – but the war was won by sea power. In August 1914 Britain, the greatest naval power of the age, controlled the oceans, cutting […]

History Guild Quiz – Advanced

History Guild Quiz – AdvancedSee how your history knowledge stacks up. Want to know more about any of the questions? Once you’ve finished the quiz click here to learn more. Have an idea for a question? Suggest it here and we’ll include it in a future quiz! The stories behind the questions 1. Where was […]

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.