Reading time: 13 minutes

The underground resistance group the East River Column played a vital role opposing Japanese forces around Hong Kong during the Second World War. Their activities provided a lifeline for Allied prisoners of war, who they aided with support, shelter, and a means of escape.

By Padej Kumlertsakul (Adviser for Overseas and Defence at The National Archives)

A band of guerrillas

Hong Kong, Christmas Day, 1941. After 18 days of brutal fighting between Japanese and British forces, the battle was drawing to a close. British defences had been overrun by the Japanese military, who were soon to take the then British Colony. But not all was lost for the retreating forces. Once the surrender was confirmed, a most dramatic escape began, led by Admiral Chan Chak, the Chinese government’s chief political and military representative in the territory. He and some 60 British officers set off across the harbour onboard the British Navy’s remaining five motor torpedo boots.

After fighting, hiding, and battling against the Japanese forces, the crew made it to a safer area of the mainland coast at Mirs Bay. Exhausted, their only chance of making it to Free China and safety was with the help of a band of guerrillas and local villagers. That band was the East River Column (ERC).

During the Second World War, the East River Column emerged as a notable faction of Communist guerrillas dedicated to opposing the Empire of Japan. With the ERC’s support and expert knowledge, Chan Chak and his crew walked for fours days through enemy lines to Huizhou and safety.

Operating in Kwangtung (Guangdong) and Hong Kong, the ERC played a pivotal role in assisting Allied prisoners of war (POWs) and internees to escape the clutches of the Japanese in Hong Kong. This underground resistance organisation dedicated itself to providing support, shelter, and a means of escape for those held captive. The National Archives holds records detailing the ERC’s activities, including accounts, maps, and award recommendations to their members.

War begins

The conflict between China and Japan began in July 1937 at the Marco Polo Bridge, and quickly escalated into a full-scale war. In North China it provided an opportunity for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to strengthen its control in rural areas; the Japanese army was focused on capturing major cities and communication centres, their occupation leaving a power vacuum in the countryside. Taking advantage of this situation, communist guerrillas infiltrated the occupied regions, rallying peasants under the banner of national resistance. The lack of state control and the threat of Japanese troops created fear among the rural elites, leading them to support the CCP’s anti-Japanese cause and cooperate for social order and collective security.

A different situation unfolded in Kwangtung, in South China. Despite Japanese aerial attacks on major cities starting in August 1937, the region was not occupied until late 1938 and early 1939. Kwangtung served as China’s rear-front line during the initial years of the war. Neither the Kuomintang (KMT), the ruling Chinese political party, nor the CCP expected the conflict to reach the province. The CCP believed that Japan would eventually invade Kwangtung, possibly at a later stage of the war, while the KMT was confident that Japan would not risk antagonizing a world power by targeting South China, which had long been under British influence. The Japanese did not finalize their plans for military operations in Kwangtung until late August 1938, and it was only in October of the same year, after much fighting, that they occupied the province.

Forming the ERC

Following the fall of Kwangtung in October 1938, a group of patriotic Chinese individuals formed an independent guerrilla unit known as the ‘Kwangtung Mass Anti-Japanese Guerrillas’ under the leadership of Tsang Sang [Zeng Sheng]. This guerrilla unit, also referred to as the East River Column, solidified its presence by combining two existing guerrilla units: the Huiyang [Wai Yeung] Bao’an People’s Anti-Japanese Guerrillas and the Dongguan [Tung Kun] Model Able-bodied Young Men Guerrillas. These units operated in the Wai Yeung and Tung Kun districts of Kwangtung province.

The alliance between the KMT and the CCP to resist the Japanese invasion, The Second United Front, saw the ERC fall under the jurisdiction of the 4th War Area of the National Revolutionary Army. This merger allowed for a more unified and coordinated resistance against the Japanese Army.

The ERC’s operations were centred around the Canton-Kowloon Railway. Its base was established in Sai Kung, a rural area in the mountains of the New Territories, serving as a buffer zone between the Japanese and the Central Government Forces. Anyone, Chinese or Westerners alike, required the assistance or permission of the ERC to enter or leave Hong Kong.

The fall of Hong Kong

On the 8 December 1941, just hours after the attack on Peal Harbor, the Japanese launched the invasion of Hong Kong. The British Empire, along with Indian troops, defended the territory against the Japanese offensive. However, the Allied forces were vastly outnumbered and ill-prepared for the attack. After a short but intense 18-day battle, the defenders were overwhelmed, resulting in their defeat.

On 25 December 1941, following heavy casualties and the inability to repel the Japanese forces, the British Governor of Hong Kong, Sir Mark Young, surrendered the territory to the Japanese. This marked the end of British rule in Hong Kong and the beginning of a brutal occupation lasting three and a half years.

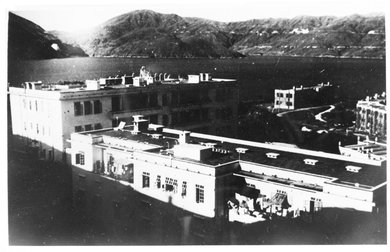

After the surrender, the Japanese established prisoner of war camps in Hong Kong. These camps primarily held Allied soldiers, including those from Britain, Canada, India, and other nations who had been captured during the battle. The conditions in these camps were harsh, with inadequate food, medical care, and rampant abuse by the Japanese captors.

One of the most infamous POW camps in Hong Kong was the Sham Shui Po Camp in Kowloon, where thousands of Allied prisoners endured extreme deprivation and mistreatment. Hong Kong island and the Kowloon Peninsula had several other POW camps, such as the Argyle Street Camp and the North Point Camp, where similar atrocities were committed. The civilian internment camp was located at Stanley.

Many prisoners and internees faced forced labour, torture, and execution, enduring immense physical and psychological hardships during their captivity. It was not until the end of the war in 1945 that they were liberated by Allied forces, marking the end of their ordeal.

The ERC’s guerrilla activities

Throughout the war, the ERC carried out relentless guerrilla activities, launching surprise attacks and engaging in acts of sabotage against Japanese forces. Their primary objectives were to disrupt enemy supply lines, gather intelligence, and weaken the occupying forces.

After the fall of Hong Kong, the ERC had grown from platoon size to battalion – around 3,000 strong – raised from the locals who knew every inch of the rugged country behind Kowloon. Their attacks mostly took place at night, when they would leave their mountain bases to make sudden and fierce assaults on Japanese strongpoints, often returning with captured arms and ammunition.

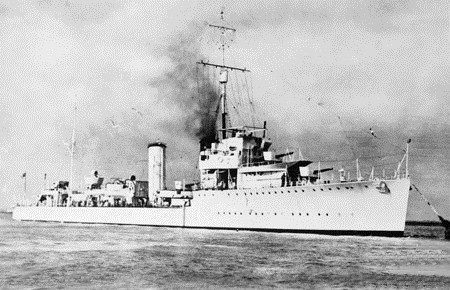

As the Column grew more experienced, it established its own navy, which consist of fishing junks armed with machine guns and rifles. On these ships, they would sneak out of the bays and inlets around Hong Kong and attack Japanese patrol boats.

Chan Chak’s escape

The ERC also played a pivotal role in assisting Allied prisoners of war and Internees to escape from Japanese POW and Internees camps located around Hong Kong and New Territories.

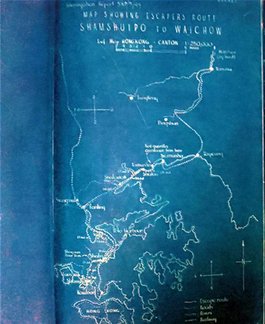

The column and local villagers were integral to Admiral Chan Chak’s successful mass escape following the surrender of Hong Kong. Once reaching Mirs Bay onboard the five small motor torpedo boats, the ERC then led the way to Free China. This escape operation laid the groundwork for an evasion route utilized by the British Army Aid Group (BAAG) and the ERC throughout the rest of the war.

Admiral Chan Chak, also known as the ‘one-legged admiral’, later became the Mayor of Canton and received a knighthood from the British for his contributions to the Allied cause. Another escapee, David MacDougall, assumed leadership of the civil administration of Hong Kong in 1945.

Francis Lee and Lieutenant Colonel Ride

Lieutenant Colonel Lindsay Tasman Ride, a professor of physiology at the University of Hong Kong, played a significant role in another noteworthy escape from the Far East during the Second World War.

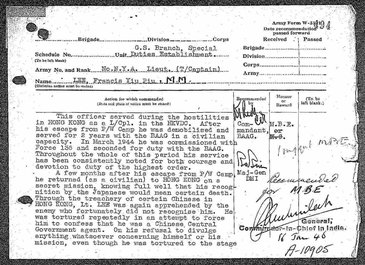

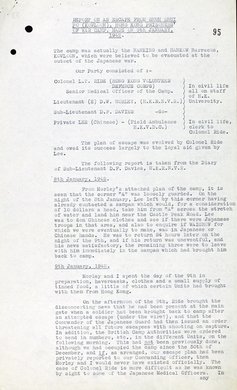

Ride served as the Officer Commanding Hong Kong Field Ambulance during the Battle of Hong Kong. After the fall of Hong Kong, he was captured and became POW at Sham Shui Po Camp. However, in January 1942, Ride, along with his Chinese clerk Lance Corporal Francis Yiu Piu Lee (nicknamed ‘Chicken Lee’) and two other British officers, managed to escape from the camp with the assistance of the ERC.

Francis Lee returned to Hong Kong in the middle of 1942 to gather information for an underground operation and liaise with the ERC in Sai Kung to setup a base for BAGG as instructed by Ride, but was arrested, tortured, and sentenced to death by the Japanese Gestapo (Kempatei). Remarkably, he managed to escape while being transferred to Shenzhen. Francis Lee’s bravery and dedication were recognized with the Military Medal and the MBE (military division).

After his escape, Ride established the British Army Aid Group (BAAG), a military escape and evasion organization in southern China. The BAAG collaborated with the East River Column, in special operations and intelligence networks. Their primary objective was to organize escape routes for POWs from prison camps in Hong Kong. The BAAG was officially classified as part of the British Directorate of Military Intelligence Section 9 (MI9), responsible for assisting prisoners of war and internees in escaping from Japanese camps.

Raymond Wong’s recommendation

Lieutenant Commander Ralph Burton Goodwin, a member of the Royal New Zealand Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNZNVR), was another notable escapee from Hong Kong.

In 1941, Goodwin served in Singapore and Hong Kong before being taken as a POW at Sham Shui Po Camp following the fall of Hong Kong. In 1944, he seized an opportunity to escape. Despite facing the challenge of navigating Hong Kong’s unfamiliar terrain without maps or knowledge of the language, Goodwin courageously ventured into enemy territory and war-torn China.

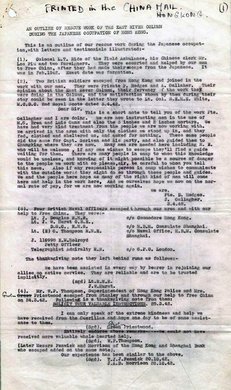

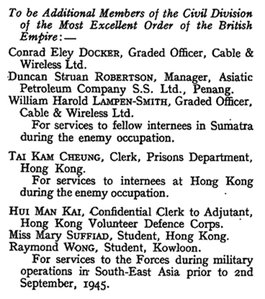

During his 12-day escape, Goodwin received assistance from Raymond Wong, also known as Huang Zuomei. Wong was a leader of the Red Chinese Guerrillas of the East River Column and was highly valued by the BAAG as one of its agents and official contact with the ERC. Wong not only provided Goodwin assistance in evading the Japanese but also offered clean clothes and hot food, which proved vital for Goodwin’s safe arrival at the BAAG Advance Headquarters in Waichow. As a result of his work in assisted BAAG, Wong was recommended for Member of British Empire.

Co-operation between the ERC and BAAG

There were many other rescues under the co-operation between ERC and BAAG, including Walter Philip Thompson, a superintendent in the Hong Kong police force. Thompson was injured by shell fragments during the Japanese takeover of Hong Kong and was detained in Stanley after the surrender.

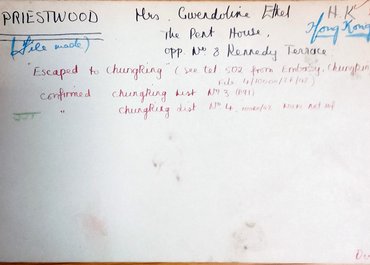

On the night of 18 March 1942, Thompson initiated an escape plan alongside another internee Gwen Priestwood. Equipped with revolver, compass and map, they crawled under the barbed wire. On the way to Free China’s wartime capital Chungking they received assistance from ERC guerrillas, leading Thompson to choose to work alongside them within the areas controlled by the Japanese. By the end of the war, he had risen to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

On 18 October 1942, two bankers, Thomas James Johnston Fenwick and John Alexander Duke Morrison, managed to escape the camp at Stanley. They boarded a sampan while being discreetly transported past two Japanese destroyers.

Along their journey, they encountered a BAAG agent who guided them through the hills to Junk Bay. After engaging in some hiking and embarking on two additional boat trips, they eventually found themselves under the protection of ERC guerrillas. These guerrillas provided them with care and support, ultimately leading them to reach the BAAG advanced headquarters at Waichow on 22 October.

The ERC’s legacy

The legacy of the ERC is multifaceted and significant. Their resistance efforts disrupted Japanese forces, provided hope to the local population, and saved numerous lives. Collaboration with British intelligence agencies strengthened their operations and intelligence gathering.

Launching surprise attacks, sabotaging enemy supply lines, gathering intelligence, the ERC’s guerrilla activities marked them as a formidable force. Their provision of support, shelter, and escape routes for those held captive, meant they played a vital role in aiding Allied POWs and internees. The experiences of ERC members during the resistance movement also shaped their contributions in the post-war period, particularly during the civil war and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China.

In recent years, the recognition of the ERC’s contributions has grown, with their bravery and sacrifices being acknowledged and remembered through various media. Their legacy endures through books, documentaries, and commemorations, ensuring that their historical importance is recognised and celebrated.

The East River Column guerrillas’ unwavering commitment to opposing Japanese occupation, aiding POWs and internees, collaborating with British intelligence, and their lasting historical impact make them a significant part of Second World War history in Hong Kong.

This article was originally published in The National Archives.

Podcasts about Hong Kong during WW2

Articles you may also like

The Political History of France, 1789-1910 – Audiobook

THE POLITICAL HISTORY OF FRANCE, 1789-1910 – AUDIOBOOK By Muriel O. Davis This little book opens on the eve of the French Revolution. The government is crippled by financial mismanagement, ruled by a King who, in the author’s words, is “devoid of both ability and energy,” and resented by a tax-oppressed peasantry and a rising […]

Weekly History Quiz No.221

1. Who led the English fleet that defeated the Spanish Armada in 1588?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.