Reading time: 7 minutes

The anti-racism protest that started in the US has spread to Europe and the world.

Protesters are not only denouncing racism but also condemning slavery in the colonial era by bringing down colonialist statues and slave traders.

In the Netherlands, protesters called for the statue of Jan Pieterszoon Coen the Governor-General of the Dutch Trade Company (VOC) in the 17th century in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) to be removed.

Slave trading was widely carried out during the Dutch colonial period in Indonesia. Especially in North Sumatra, human trading for plantation workers, known as coolies, was widely practiced around 150 years ago.

Last year, I took some Australian students to Medan, as part of the New Colombo Plan program, to learn about plantation agriculture in North Sumatra. During the trip, I began researching about the soil in North Sumatra. I found out many pieces of research had been carried out in the colonial era on the soils of Deli.

The region near Medan is famous for its Deli tobacco, and colonial planters researched how to boost tobacco production. Behind the golden age and success of Dutch research, I found enormous human casualties that built plantations in North Sumatra. Widespread racism and slavery occurred in plantations managed by colonial companies.

Memorial of slave traders

Although some novels and academic writings have described the life of indentured labour in North Sumatra, the general public rarely discuss the history of slavery.

Even until the end of the 20th century, the Dutch government never acknowledged the violence during colonial times.

Medan, famous as a trading city in the early 20th century, once erected two monuments to commemorate the glory of slave traders. In 1915, a fountain was erected in front of the Medan Post Office to commemorate Jacob Nienhuys as the “pioneer” of the Deli plantation.

In 1928, the statue of Jacob Theodoor Cremer was erected in front of the Deli Plantation Association office building (now the Putri Hijau military hospital) with an inscription “Cremer, 1847-1923. The founder of Deli tobacco plantations, the founder of the railway in Deli, a tireless warrior who worked for the benefit of this plantation country”.

These two monuments no longer exist, but the legacy of coolies from the two colonial figures can still be felt today in North Sumatra.

The history of coolies in Deli

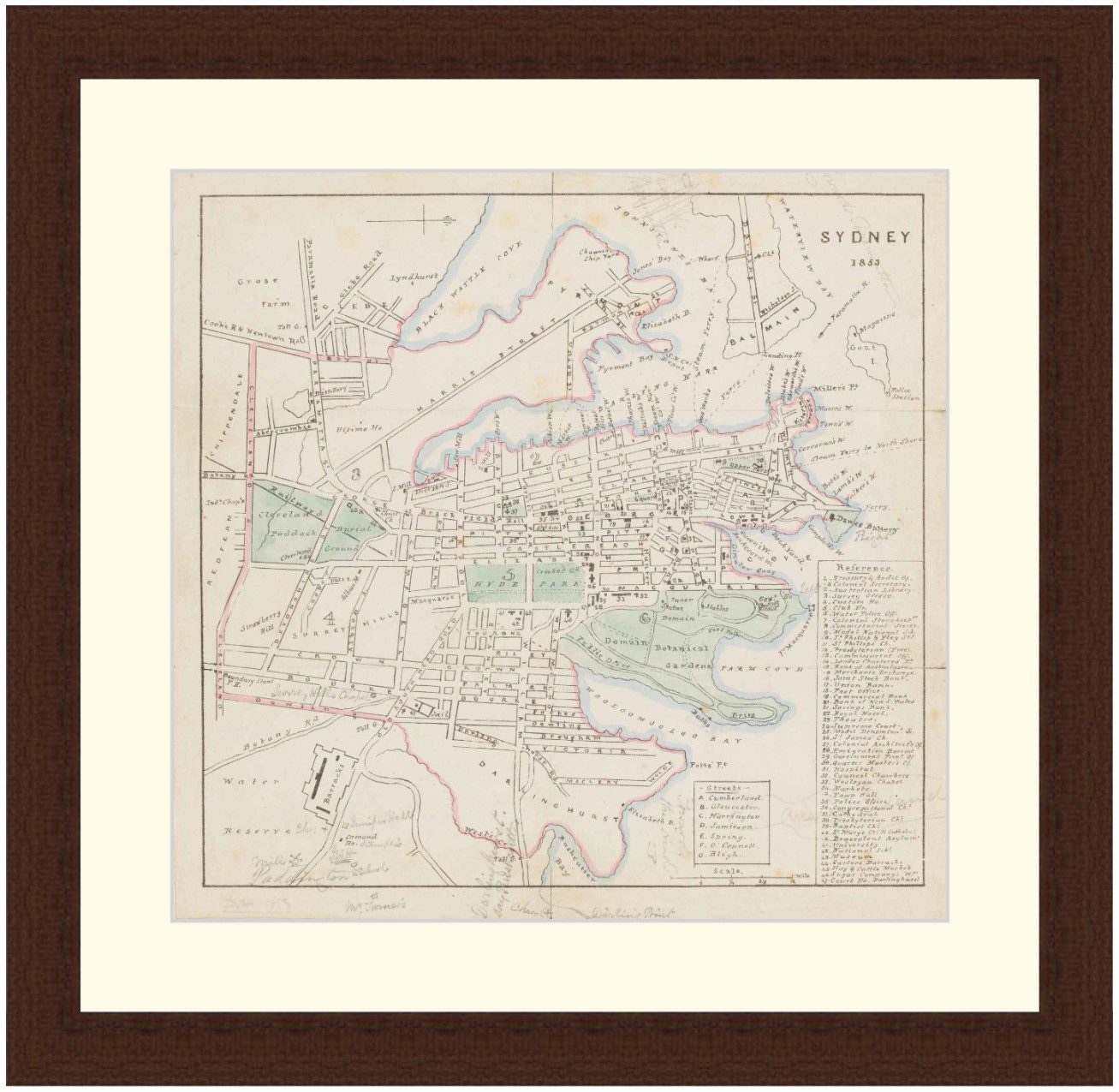

The story goes that Jacob Nienhuys, a Dutch tobacco trader, came to Labuhan Deli in North Sumatra in 1863. Labuhan was a small village near Belawan, inhabited by only 2,000 Malay residents and about 20 Chinese and 100 Indians.

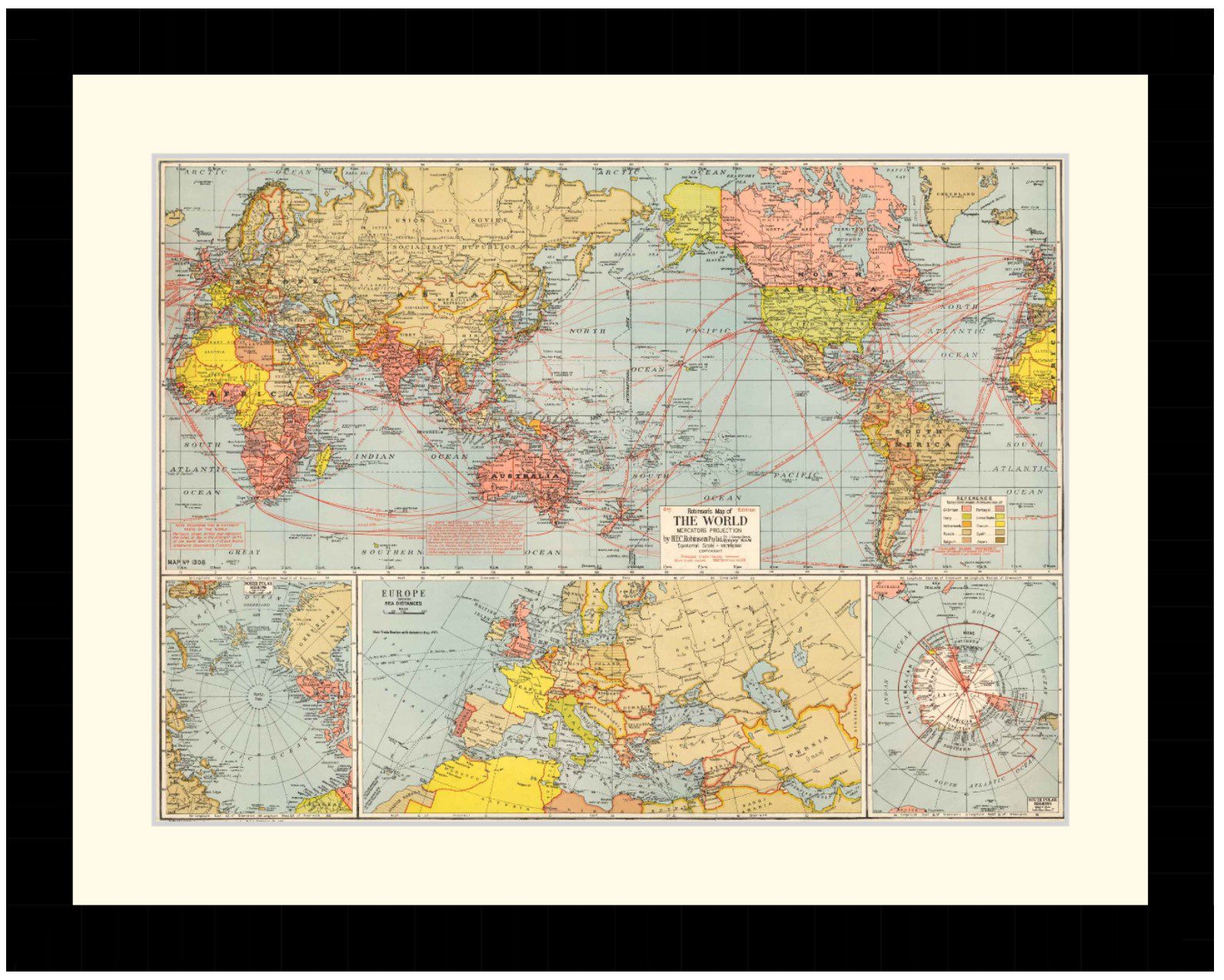

The Dutch colonial government had just abolished the cultuurstelsel (or enforced planting) policy and implemented a “liberal” economic system in the Dutch East Indies, which was open to private companies.

The Sultan of Deli, Sultan Ma’ mun Al Rashid Perkasa Alam (1853-1924), was interested in developing land in Deli as a plantation area. He gave a land concession to Nienhuys to grow tobacco. The first problem faced by Nienhuys was a lack of labour. Local Malays and Bataks did not want to work as plantation labourers.

Nienhuys then sought labour by “importing” 120 Chinese coolies from Penang, Malaysia in 1864. After several years of trials, Nienhuys successfully developed Deli tobacco as a high-quality cigar wrapper sought after by European and American smokers.

With a capital investment from Rotterdam, Nienhuys founded the Deli Maatschappij or Deli Company and developed industrial, large scale tobacco plantations in Deli.

With the rapid development of plantations, he needed more workers. Every year, thousands of Chinese coolies were brought in from Penang and Singapore. Workers from Java, Banjar, and India were also shipped in.

In 1890, the Dutch transported more than 20,000 Chinese coolies to Deli. With cheap labours, tobacco companies could run a very profitable business. In 1896, the sale of 190,000 bales of Deli tobacco in Amsterdam brought in 32 million guilders. If converted to the current money, it is around US$450 million.

The total Deli tobacco sales accomplished by colonial planters from 1864 to 1938 reached 2.77 billion Guilders, or if converted to current currency is around US$40 billion.

White racism

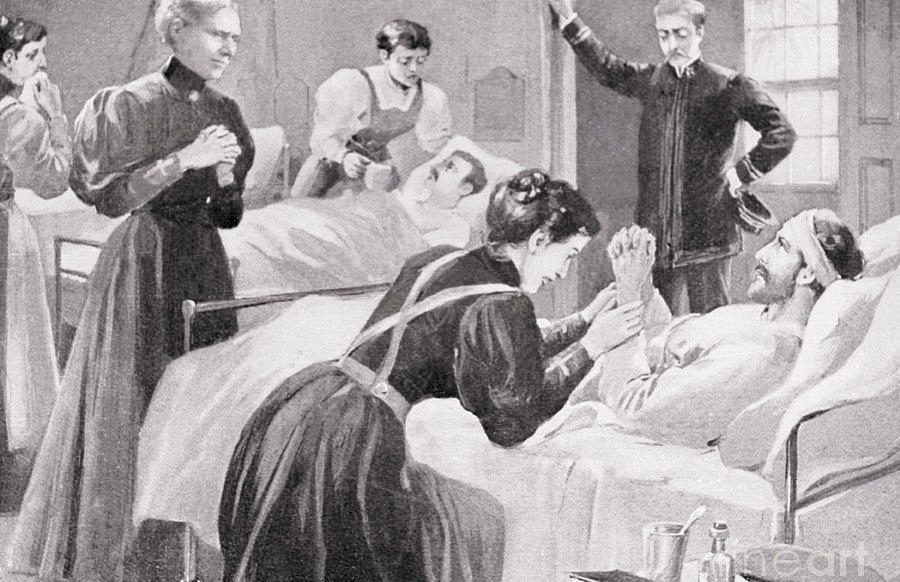

The Dutch planters treated the coolies inhumanely and like slaves.

A letter dated October 28, 1876, by Frans Carl Valck, the Assistant Resident in East Sumatra noted:

“It would be a miracle indeed, if respectable Chinese coolies would be attracted to a place where coolies are beaten to death or at least so mistreated that the thrashings leave permanent scars, where manhunts are the order of the day. …. Just recently I heard a rumour about a certain European who prided himself on having hung him down after the coolie had turned entirely blue.”

Nienhuys wrote that “Chinese are bold arch-swindlers and the Javanese are lazy and hot tempered” and “Batak is a stupid race, on the whole”.

An article dated May 30th, 1913 in Sumatra Post wrote that around 1867, Nienhuys was indicted of flogging seven Chinese coolies to death. The case was never proven nor disproved, but the Sultan of Deli ordered Nienhuys to leave the land of Deli and never to return.

In 1869, JT Cremer replaced Nienhuys as the administrator of the Deli company. To control thousands of workers from China and Java, Cremer designed the Coolie Ordinance, passed by the Dutch East Indies government in 1880. The regulation allowed companies to engage coolies in a contract that bound them for three years. The workers were meant to pay for their “debt” of transportation cost to Deli land.

The contract included a penal sanction that allowed the company to punish the workers if they forfeited the agreement. The ordinance gave power to the planters to punish coolies who were thought to be disobedient, lazy or tried to run away.

Monopoly and Brutality

The Deli Tobacco Planters Association was founded in 1879 to monopolise tobacco plantations in Deli. Cremer also lobbied the Dutch government to bring in workers directly from mainland China. In 1900, 6,900 workers were brought directly from the ports of Swatow in Guangdong Province and Hong Kong. From 1888-1930, more than 200,000 Chinese workers had been shipped into Deli.

Starting in 1910, coolies were also shipped from Java as new rubber plantations were established. By 1930 there were 26,000 Chinese, 230,000 Javanese, and 1,000 Indians working on Deli plantations.

In 1902, Van der Brand, a Dutch lawyer in Medan, revealed the brutality of colonial planters towards their workers in a pamphlet entitled “Millions from Deli (De Millionen uit Deli)”. This publication is considered the Max Havelaar of Deli.

The colonial government felt obliged to respond and send a prosecutor J.L.T. Rhemrev to investigate the case. Rhemrev’s report in 1904 described even worse treatments to the workers. But the report was filed away, and only in 1987 discovered by Jan Breman, a researcher from the University of Amsterdam.

Anticolonial activist from Indonesia, Tan Malaka, who was teacher a in Deli plantation in the 1920s, described the life there:

Deli, a land of gold, a haven for the capitalist, but a land of sweat, tears, and death, a hell for the workers.

The coolies were forced to work; they were slaves. The coolies worked from dawn to night, received enough wages to fill in their stomachs and cover their back; they lived in a shed like goats in their cages, they were called godverdom and could be beaten any time and could lose their wives and daughters as desired by the master.

Breman estimated that a fourth of the coolies died before their contract ended.

Legacy of colonial plantations

After Indonesian independence, this case of slavery had been forgotten, both in the Netherlands and in Indonesia.

In addition to the destruction to humanity, Dutch and European colonial companies, in developing plantations in North Sumatra, have cleared a massive area of virgin forests. Karl Pelzer, an academic from Yale University, estimated that more than half of the land in Deli Serdang and Langkat Regencies had been cleared for plantations during the Dutch colonial period.

The legacy of the Dutch plantation system still lingers. Plantations in North Sumatra still apply the colonial administration system, with an administrator, a plantation assistant, clerks, foremen, and labourers.

A large amount of Javanese still work in plantations, while they are no longer bound by the contract, the labor wage is still minimum.

The romanticism of Deli

Lately, the rich history of Deli land has been romanticized as a land of rich historical heritage.

Along with this beautiful fairy tale, Nienhuys is narrated as the founder of the modern city of Medan. The Dutch Colonial Monument website glorifies Cremer as the colonial with the highest ideals that brought civilization, prosperity, peace, and order.

Nienhuys and Cremer became wealthy from the Deli plantations. Nienhuys’ house in Amsterdam is now the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies. It has a display of Nienhuys’ special golden bathroom. Cremer even served as a colonial minister in the Dutch government (1897-1901).

The Wikipedia pages of Nienhuys and Cremer paint them as the founders of a tobacco company and a tobacco magnate and do not list the slavery system that they had created.

The romanticism of Medan’s history must not forget the sweat and blood of hundreds of thousands of indentured workers who were enslaved on plantations during colonial times.

Podcasts about Dutch colonial Indonesia:

Articles you may also like:

The Life of Clara Barton – Volume 2 – Audiobook

THE LIFE OF CLARA BARTON – VOLUME 2 – AUDIOBOOK By William E. Barton (1861 – 1930) Clarissa Harlowe Barton (December 25, 1821 – April 12, 1912) was a pioneering American nurse who founded the American Red Cross. She was a hospital nurse in the American Civil War, a teacher, and a patent clerk. Since nursing […]

Remembering Long Tan: Australian army operations in South Vietnam 1966–1971

Reading time: 5 minutes

The anniversary of Long Tan reminds most Australians that despite winning that iconic high intensity battle, the Australians and New Zealanders lost the Vietnam War. In fact, the First Australian Task Force (1ATF) fought at least 16 big battles, and through superior firepower from artillery, armor and airpower, won them all, sometimes by a narrow margin.

But most of the struggle in Phuoc Tuy province and South Vietnam was a prolonged low intensity guerrilla war. The big battles only mattered if the US and her allies had lost them, as big battle success allowed the allies to stay in the War. Enemy defeats just forced the enemy to revert to low intensity guerrilla war, which the allies had to control if they were to win.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.