Reading time: 5 minutes

The national effort at remembering should also revisit a series of 50-year anniversaries for Australia’s entry and enmeshment in the Vietnam War.

Vietnam might have more to offer than Gallipoli or the Western front in thinking about Australia’s regional future, the US alliance and the diplomatic and defence choices of the 21st century. The frame of history is always shifting and the lessons drawn are forever changing in shape and taste. And as the historian Peter Edwards dryly notes, to a new generation of Australians, ‘Vietnam is as remote as the Boer war was to young people in the 1960s.’

By Graeme Dobell, Australian War Memorial.

To get around that problem, Edwards has returned to the ground he worked as the Official Historian and general editor of the nine-volume Official History of Australia’s Involvement in Southeast Asian Conflicts 1948–1975. The result is a new history for a new century of the one war in the 20th century where Australia was on the losing side: Australia and the Vietnam War. The book was launched by the Governor-General designate, General Peter Cosgrove.

To see why Vietnam still tears at the Australian polity, turn to the 2006 memoir by Cosgrove (who was awarded the Military Cross for actions as a Lieutenant in Vietnam) and the conclusion in his Vietnam chapter that Australia’s involvement in Vietnam was a mistake:

…in retrospect we should not have gone… I remember with sadness that over 500 Australians were killed in that war and many more wounded and maimed; … And we left. And we lost. We mustn’t do that with our men and women. Sending troops to war is without doubt the most difficult and agonising decision for any leader. My advice to leaders is never to take the decision lightly, and having done so, never stop until the outcome is worth the cost.

Cosgrove’s sentiment reflects what Edwards describes as the common view that took hold after 1975—Vietnam was at best a strategic mistake, at worst immoral.

In writing a new version of the history for today’s Australia, Edwards follows much of that familiar narrative but upends some of the old Vietnam conclusions, finding elements of Australian alliance success and regional strategic success in the losing war. While the long view offered is rosier, the Vietnam blunders are still paraded for punishment.

In entering the war, Robert Menzies thought ‘he was simply repeating a winning formula that would achieve military success in Southeast Asia, strengthen the alliance with the US and divide the Labor Party’s right and left wings.’ The Vietnam commitment was ‘imprudent and overconfident’ and put ‘blind faith’ in US military power. Whatever gains could be made in Vietnam had been achieved by 1968–69, when the US and Australia should have made an exit. Instead, the blood kept flowing and the trauma turned to nightmare because of ‘unrealistic definitions of ‘victory’ as much as the lack of clear political and military strategies’.

Edwards recalibrates the alliance calculus in Australia’s favour and gives a fresh embrace to the domino theory—that if Vietnam had fallen to communism in 1965 instead of 1975, the other dominos of Southeast Asia would have wobbled badly or even toppled: ‘With half a century’s hindsight, the ‘domino theory’ arguments gain at least some element of credibility; but as with the ‘insurance policy’, at a cost that was unnecessarily high’.

The ‘insurance’ revision is to reject the idea that in Vietnam, Australia was fighting ‘other people’s wars’. Instead, Edwards argues the US was fighting for Australia’s regional interests and Australia gained some of its strategic objectives: ‘[I]n the minds of Menzies and his principal advisers, it was a matter of getting the US to fight a war for Australia’s security. Paying a premium for Australia’s strategic insurance with the US was not of itself wrong, but should have been handled with a great deal more care’.

Edwards’ case is that Australia should’ve been the loyal ally that asked hard questions and questioned every promise made by its large ally. And this is no mere confected counterfactual. The history gives much weight to the way Australia handled its major ally Britain, and dealt with Indonesia as temporary enemy but eternal neighbour in the Confrontation crisis from 1963 to 1966. The same Canberra cast that stumbled into Vietnam got much right in handling the diplomatic and military dramas of Sukarno’s Konfrontasi against the proposed federation of Malaysia. In his speech at the launch, Edwards contrasted Australia’s skill in dealing with Britain and Indonesia versus the unquestioning meekness applied to US operations in Vietnam:

We need to look again at a time when we were becoming embroiled in two conflicts, in two different parts of Southeast Asia, with two different allies. In one, [Confrontation] the Australian political, diplomatic and military actions were co-ordinated and nuanced; those policies emerged from robust discussions between ministers and their advisers, both civilian and uniformed; the government engaged in vigorous independent diplomacy, especially in regional capitals, deploying a competent foreign service in which the government had confidence; our political and military leaders discreetly but robustly challenged our major ally’s diplomatic and military approaches; and our servicemen were able to apply their preferred tactics, fighting alongside allies in whose approaches they had confidence.

In the other conflict [Vietnam], policy debate was suppressed; experienced advisers were sidelined or disregarded; we failed to seek adequate information about, let alone question, our ally’s strategies; our diplomacy was subordinated to alliance considerations; and our servicemen found themselves fighting a war in ways which were often at odds with their own operational concepts. It is no coincidence that, by any cost-benefit analysis, Australia gained a better outcome from the first conflict than from the second.

Edwards describes history as a never-ending conversation between the present and the past about the future. As an example of that conversation, here is the ASPI interview with Peter Edwards.

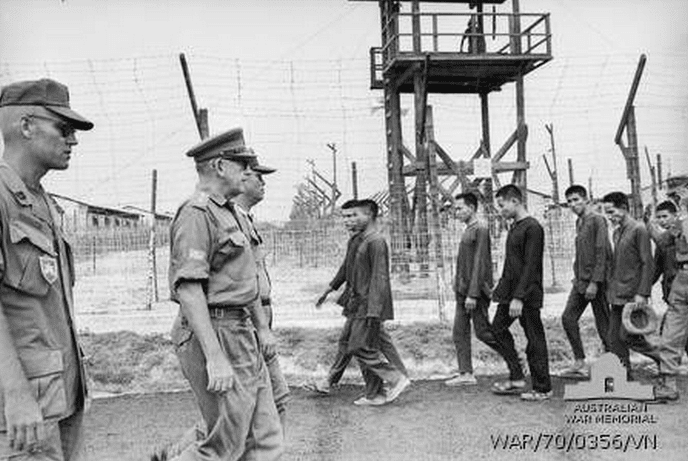

Graeme Dobell is the ASPI journalism fellow. Image courtesy of the Australian War Memorial.

This article was originally published in The Strategist.

Podcasts about Australian Vietnam War experience:

Articles you may also like:

WA’s first governor James Stirling had links to slavery, as well as directing a massacre. Should he be honoured?

Today, councillors in Perth’s City of Stirling will vote to decide whether to change their city’s name. This follows a residents’ motion arguing a new name would better “reflect the long standing and relevant history of this land in such a way that is inclusive and in recognition of the Nyoongar community”. This is not about erasing […]

The text of this article is republished from The Strategist under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License in accordance with their republishing policy.