Reading time: 7 minutes

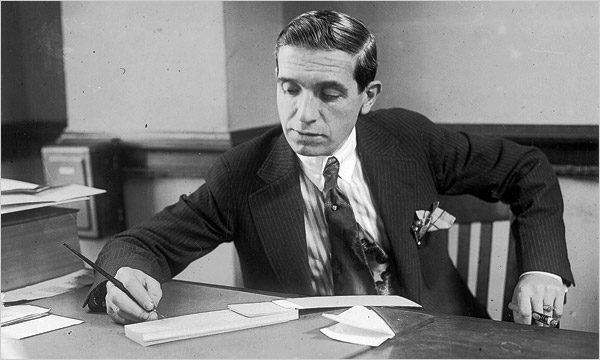

Having gambled away his life savings on the passage over, Italian immigrant Charles Ponzi arrived in America with next to nothing in his pocket. As he would later recount, “I landed in this country with $2.50 in cash and $1 million in hopes, and those hopes never left me.”

These lofty ambitions led Ponzi to take on a colorful array of odd jobs in the 1900s and 1910s—from translation work to nursing at a mining camp to painting signs. His roundabout career led him eventually to a tenure at a bank—Banco Zarossi in Montreal. This experience proved formative for Ponzi: it was his first encounter with the scam that would come to bear his name.

By Mye Brooks.

Banco Zarossi attracted its clientele with the promise of 6% interest payments—double the going rate. However, due to some unfortunate real estate investments, the bank was unable to make those payments legitimately. Instead, it used deposits from new investors to pay back older investors: robbing Peter to pay Paul.

Of course, this charade eventually broke down—Zarossi himself fled to Mexico with the remaining money, and his employees—including Ponzi—were left penniless. The ensuing strife led Ponzi to venture into white-collar crime himself: he forged a check for $423.58. When confronted by authorities concerning his unusual expenditure, Ponzi confessed. He spent three years in prison—but in letters to his mother in Italy, he simply said that he’d landed a job as an assistant to a prison warden.

Following his prison term, Ponzi settled in Boston. He married in 1918 and subsequently ran his wife’s family business into the ground. Still, he never lost his million-dollar hopes—and in late 1919, those hopes caught fire.

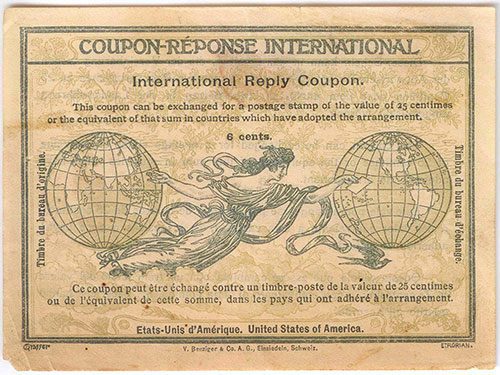

It started very simply: Ponzi received a piece of international mail. Enclosed with the letter was something called an international reply coupon (IRC). This was a voucher that could be bought for the price of a stamp in one’s own country, mailed internationally, and then redeemed for a stamp at a post office in the recipient’s country: a way to pay for a faraway correspondent’s postage.

Most people wouldn’t have looked twice at such a thing, but Charles Ponzi did—and he saw dollar signs.

Following World War One and the Spanish Flu pandemic, European currencies had devalued significantly. This impacted the price of postage: a person could buy three IRCs in Italy for the price of one IRC in America. Those coupons could then be exchanged in America—effectively purchasing three stamps for the price of one.

Ponzi leapt into action, incorporating the Securities Exchange Company in January of 1920. From there, he found great success convincing people to invest, promising 50% returns in 90 days.

Naturally, some were skeptical of Ponzi’s get-rich-quick scheme. While buying a product for a low price in one market and then selling it for a higher price in another market—a practice called ‘arbitrage’—is legal, there were other unanswered questions. How did Ponzi plan to buy Italian IRCs in bulk? How did he plan to transport the coupons en masse to America? And, upon arrival, how did Ponzi plan to turn stamps into cash?

Ponzi easily shrugged off these suspicions. Of course he couldn’t divulge that information—to investors or to anyone! It was his trade secret.

But even if Ponzi had been willing to answer those questions, he wouldn’t have been able to. He didn’t have those answers himself! The real ‘trade secret’ of the Securities Exchange Company was that Ponzi never bought any international reply coupons. All of his initial investors were paid with money from newer investors.

Ponzi’s racket snowballed at an incredible speed. In January of 1920, 18 people invested a total of $1800. By July of that year, new investors—from paperboys to finance executives to a whopping two-thirds of the Boston police force—made Ponzi nearly a million dollars every day.

This success funded an opulent lifestyle. Ponzi bought a mansion, a Locomobile, a first-class ticket to bring his mother stateside. He had cracked the American dream. As one admirer put it: “Columbus discovered America… but [Ponzi] discovered money.”

Of course, fame and fortune always bring contempt and suspicion—but Ponzi dealt ably with his opponents. When the Boston Post ran an article contending that there was no way Ponzi could be making so much money by legitimate means, Ponzi sued the author for libel and won half a million dollars.

Still, the Post was tenacious in its search for the truth of Ponzi’s success. Several subsequent articles led to turbulent public opinion: sometimes, Ponzi would arrive at his office to find investors clamoring for their money back. He repeatedly calmed these mobs, however, handing out coffee and donuts and cashing out those who wished to jump ship. Conversely, on July 26, 1920, Ponzi found throngs of people waiting to hand over their money. As he recalled in a memoir, “a huge line of investors, four abreast, stretched from the City Hall Annex… all the way to my office!” Ponzi remembered that “to the crowd there assembled, I was the realization of their dreams… the ‘wizard’ who could turn a pauper into a millionaire overnight!”

In the face of this hullabaloo, however, the case against Ponzi was mounting. The Massachusetts district attorney had ordered an investigation into Ponzi’s enterprise. Negative press continued, and when Ponzi hired publicist William McMasters to repair his reputation, McMasters immediately discovered that Ponzi was a fraud, collected incriminating documents, and sold the story to the Boston Post for $5,000. Suspicious banks barred Ponzi from withdrawing any money.

Finally, on August 11, 1920, the Post ran an article revealing Ponzi’s involvement with the crooked Banco Zarossi and his subsequent conviction for forgery. At last willing to read the writing on the wall, Ponzi turned himself in shortly after. He was convicted of mail fraud and served three and a half years of a five-year sentence.

The collapse of Ponzi’s scheme was disastrous. Several banks failed in its aftermath, and his investors were devastated. Many had reinvested their profits into the scam instead of cashing out, and lost their life savings. Their losses amounted to $20 million in 1920 dollars, approximately $222 million in 2022 dollars.

Still, Ponzi was unrepentant. He continued to run cons in America and elsewhere, and, later in life, gave an interview expressing great pride in his magnum opus. “Without malice aforethought, I had given them the best show that was ever staged in their territory since the landing of the Pilgrims! It was easily worth [the money] to watch me put the thing over.”

Shortly afterward, in January of 1949, Ponzi died in the charity ward of a Brazilian hospital. He had $75 to his name, all of which was put toward his burial. Still, despite this ignominious end, the Ponzi scheme persists in infamy, immortalized in our language.

Podcasts about Charles Ponzi

Articles you may also like

Australia’s first known female voter, the famous Mrs Fanny Finch

Reading time: 7 minutes

On 22 January 1856, an extraordinary event in Australia’s history occurred. It is not part of our collective national identity, nor has it been mythologised over the decades through song, dance, or poetry. It doesn’t even have a hashtag. But on this day in the thriving gold rush town of Castlemaine, two women took to the polls and cast their votes in a democratic election.

General History Quiz 211

1. Which Battle saw Henry V of England order the French prisoners he had captured to be executed?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

General History Quiz 140

1. Who did the 1521 Edict of Worms decree was “a notorious heretic”?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.