Reading time: 12 minutes

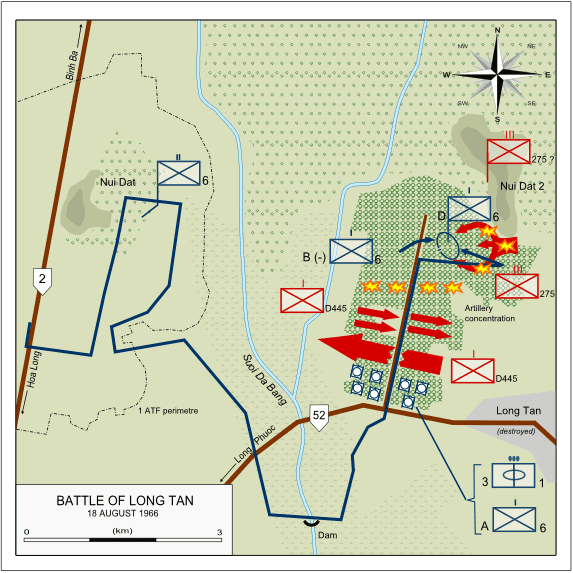

The Battle of Long Tan, fought on August 18th, 1966, is a key battle in Australian military history, and the reason 18th August is designated as Australia’s official Vietnam Veterans’ Day. It was an early defining engagement for the 1st Australian Task Force (1 ATF) during their deployment in Vietnam, where the 108 men of D company, 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR), encountered a vastly superior Viet Cong (VC) force. The battle took place in a rubber plantation near the village of Long Tan in Phuoc Tuy Province, an area where Australia had been assigned responsibility for security.

By David Phillipson

Strategic Background and Preparation

In mid-1966, Australia’s military involvement in Vietnam escalated from the earlier deployment of the Australian Army Training Team, Vietnam with the establishment of 1 ATF in Phuoc Tuy Province. The base at Nui Dat, constructed in the midst of VC-controlled territory, served as the hub for Australian operations aimed at disrupting VC activities and securing the province. The Australian strategy focused on aggressive patrolling and establishing dominance over the area, a task they had trained extensively for, as well as having recent experience from service in the Malayan Emergency and Indonesian confrontation.

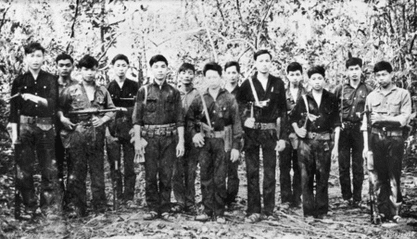

The VC forces in Phuoc Tuy included the 275th Regiment of the 5th Division, a well trained and equipped VC main force unit and the D445 Battalion, a VC local force battalion, which had been operating in the region for some time. These units were well-versed in guerrilla tactics and had a strong local support network, which they leveraged to resist the Australians. Their mission was to isolate the eastern provinces from Saigon by interdicting the main roads and highways, in this they posed a direct threat to the Australians.

Prelude to the Battle

In the days leading up to the battle, the Australian 547 Signal Troop, a signals intelligence unit, had been monitoring the movements of a VC radio transmitter believed to be part of the 275th Regiment. This intelligence indicated that a significant VC force was moving towards Nui Dat. However, patrols sent out found no signs of the enemy, leading to uncertainty about the exact location and intentions of the VC.

On the night of 16th-17th August 1966, the VC launched a mortar and recoilless rifle attack on the Australian base at Nui Dat. The 22 minute bombardment wounded 24 soldiers and caused damage to the base, but was not followed up with a ground attack. The base remained on alert as patrols were dispatched the following day to locate the firing positions and pursue any withdrawing enemy forces.

D Company, 6RAR, under the command of Major Harry Smith, was one of the units sent out on patrol on August 18. The company, consisting of 108 men, including a New Zealand artillery forward observer party, left Nui Dat at 11:00 AM.

“I trained the company the way I wanted to train them, based on my experiences in Malaya, where I was a Platoon Commander and where I shot my first enemy and I wanted to see my soldiers go into action with the best possible background, weapon training, teamwork and esprit de corps that we could possibly have and in retrospect, I believe that we achieved that.”

LT COL Harry Smith

As they moved eastward towards the Long Tan rubber plantation, the sounds of a concert being held at the base by Australian entertainers Col Joye and Little Pattie could be heard. It had been decided that there was little risk of a major engagement, so the Australian troops not on patrol could enjoy some time off and watch the concert.

Initial Contact and Escalation

At approximately 3:15 PM, as D Company entered the Long Tan rubber plantation, the Australian troops were alert but not expecting significant action. Shortly after entering the plantation, 11 Platoon, led by Second Lieutenant Gordon Sharp, made brief contact with a small group of VC soldiers. The enemy quickly withdrew, but the encounter suggested the possibility of a larger force in the vicinity. The Australians were soon to discover they were facing far more than just a small VC patrol.

At 3:40 PM, 11 Platoon, advancing in extended line, came under intense fire from a concealed enemy force. The VC, positioned in depth with automatic weapons, RPGs, and mortars, launched a ferocious attack. Within minutes, the platoon was pinned down, and casualties began to mount. The sudden onslaught took the Australians by surprise, unlike the usual hit-and-run tactics of the local guerrillas, the VC in this encounter stood their ground and engaged the Australians in a pitched battle. This was different to what Australian training and recent experience in counter-insurgency warfare had prepared them for.

As the fighting escalated, the afternoon monsoonal downpour began, further complicating the situation. The heavy rain reduced visibility to a few meters and turned the ground to mud, making movement difficult and communication between platoons nearly impossible. 11 Platoon was soon isolated from the rest of D Company, and their situation became increasingly desperate. The platoon commander, Lieutenant Sharp, was killed while trying to direct artillery fire to support his beleaguered men. His death left Sergeant Bob Buick in command, and under his leadership, the platoon continued to resist the VC onslaught, despite being nearly surrounded and running low on ammunition.

Decisive Artillery Support

Artillery fire from Nui Dat played a crucial role in the survival of D Company during the battle. The forward observer party, led by New Zealander Captain Maurice Stanley, called in fire missions from the 161st Battery, Royal New Zealand Artillery, and 1st Field Regiment, Royal Australian Artillery, as well the American 2/35th Artillery Battalion’s 155 mm guns. The artillery bombardment was intense, with more than 3,000 rounds fired over the course of the battle, often landing just meters in front of the Australian positions.

The accuracy and intensity of the artillery fire were decisive in disrupting the VC assaults. Time and again, the VC massed for an attack, only to be broken up by the devastating impact of the artillery. The terrain of the rubber plantation, with its rows of trees and open ground between them, allowed the shrapnel from the shells to inflict maximum damage on the attacking forces. The artillery fire was so effective that it prevented the VC from overrunning the Australian positions, despite their significant numerical advantage.

However, the artillery was not without its challenges. The heavy rain made it difficult for the forward observers to accurately adjust the fire, and communication problems exacerbated the situation. At one point, 10 Platoon’s radio was damaged, and a runner had to be sent through enemy fire with a spare radio to restore communications. Despite these difficulties, the artillery remained a lifeline for D Company, providing the firepower needed to hold off the enemy.

A Desperate Fight for Survival

As the battle wore on, the situation for D Company became increasingly dire. By 4:30 PM, both 10 and 11 Platoons were heavily engaged and taking casualties. Major Smith ordered 12 Platoon, under Second Lieutenant Dave Sabben, to move up and reinforce the beleaguered platoons. However, 12 Platoon soon found itself under attack as well, and the entire company was at risk of being overrun.

By 5:00 PM, D Company was nearly surrounded. The VC had succeeded in getting behind 11 Platoon, cutting off their retreat. Despite the heavy casualties and the dire situation, the Australians continued to fight back, relying on their training and the support of the artillery. The relentless pressure from the VC, combined with the deteriorating weather and low ammunition, made it clear that without reinforcements, D Company would not be able to hold out much longer. The riflemen of D Company began the engagement with 120 rounds of ammunition each for their L1A1 Self-Loading Rifles. This was more than enough for their expected role of patrolling to find small groups of irregular enemy forces, but was quickly consumed in an ongoing battle with enemy main force units.

Recognising the severity of the situation, Major Smith requested resupply of ammunition by air. At 6:00 PM, two RAAF UH-1B Iroquois helicopters braved the heavy rain and enemy fire to drop boxes of ammunition to the embattled soldiers. The resupply was a critical moment in the battle, arriving just as the Australians were down to their last few rounds. Warrant Officer Class 2 (WO2) Jack Kirby, the company sergeant major, played a pivotal role in distributing the ammunition under fire, ensuring that the men could continue the fight. The ammunition needed to be loaded into magazines, a tough task under fire, in the rain. This was a lesson the Australians learnt for future engagements, when they provided ammunition resupply already loaded into magazines.

The Arrival of Reinforcements

Meanwhile, at Nui Dat, a relief force was being assembled. A Company, 6RAR, along with a troop of APCs from 3 Troop, 1st Armored Personnel Carrier Squadron, was ordered to move out and relieve D Company. The journey to Long Tan was slowed by the heavy rain which had swollen the Suối Da Bang creek, making it difficult for the APCs to cross. The threat of ambush along the route also meant that the relief force had to proceed with some caution.

As the APCs commanded by Lieutenant Adrian Roberts approached the battlefield, they encountered a company of VC soldiers attempting to outflank D Company. The APCs opened fire with their .50 caliber machine guns, catching the enemy by surprise and inflicting heavy casualties. The sudden appearance of the APCs and their firepower turned the tide of the battle. The VC, who had been massing for another assault on D Company, were forced to withdraw.

At 7:00 PM, just as daylight was fading, the APCs broke through to D Company’s position. The arrival of the reinforcements was a pivotal moment. Exhausted, low on ammunition, and with many wounded, the men of D Company had been holding on by sheer determination. The sight of the APCs, with their heavy weapons and fresh troops, gave the Australians a much-needed boost in morale and provided the firepower necessary to secure the area.

The Battle’s Conclusion and Aftermath

With the arrival of the reinforcements, the VC began to disengage and retreat into the surrounding jungle. The rain and darkness provided cover for their withdrawal, and by 7:30 PM, the battle was effectively over. The Australians, exhausted and battered, held their positions through the night, wary of a possible return by the enemy. However, the VC did not return, and the next morning, Australian forces moved out to assess the situation and recover their dead.

The battlefield presented a grim scene. The Australians found 245 bodies of VC soldiers, many of them killed by artillery fire. However, it was clear that many more bodies had been removed during the night, following normal VC doctrine. The Australians suffered 18 killed and 24 wounded, a heavy toll for such a small force. Another Australian soldier died of his wounds later. Despite the high casualties, the battle was a victory for the Australians, who had inflicted significant losses on a much larger enemy force, as well as maintaining control of the area surrounding their base at Nui Dat.

The Battle of Long Tan had significant ramifications both on the battlefield and back home in Australia. Militarily, it demonstrated the effectiveness of Australian training, tactics, and combined arms operations. This training is detailed in the podcast series below, which provides an excellent insight into the Australian Army’s approach to the early stages of the Vietnam War. The coordination between infantry, artillery, and armored support was a key factor in the victory, as was the resilience and discipline of the Australian soldiers under extreme conditions. The battle also highlighted the continuing importance of artillery in modern warfare, as the New Zealand and Australian gunners had played a decisive role in the outcome.

In the aftermath of the battle, the VC forces in Phuoc Tuy Province were significantly weakened, and their ability to operate openly in the area was severely curtailed. The Australian forces continued to conduct aggressive patrols and operations to maintain control of the province, but the battle marked a turning point in their campaign. The VC, although not completely defeated, were forced to adopt more cautious tactics, and the Australians were able to consolidate their hold on the province.

Commemoration and Legacy

The bravery and sacrifice of the men who fought at Long Tan have been commemorated in various ways. August 18th, the date of the battle, is now recognised as Vietnam Veterans’ Day in Australia, honouring all Australians who served in the Vietnam War. The Long Tan Cross, originally erected on the battlefield in 1969, stands as a symbol of the sacrifice made by those who fought there. The cross has become a pilgrimage site for Australian veterans and their families, a place of reflection and remembrance.

Podcasts about the Battle of Long Tan

Below are three excellent podcast series examining the Battle of Long Tan. First is the brilliant two part series by History Guild contributor Warwick O’Neill from the Australian Military History podcast. This provides a comprehensive run through of the battle, including recordings of actual radio messages from the Australians during the battle.

This is followed by two detailed and insightful series from The Principles of War podcast, which examine the experiences of the Australian troops in detail, beginning with their training, doctrine and previous combat experience, before drilling down into the individual elements of the battle and aftermath. It includes extensive interviews with LT COL Harry Smith and 2LT Dave Sabben, both officers who fought in the battle.

Articles you may also like

What was The Schlieffen Plan?

Reading time: 4 minutes

France to the west, Russia to the east; Germany had a strategic plan to prevent full-scale war in the early 20th century. So why did it fail?

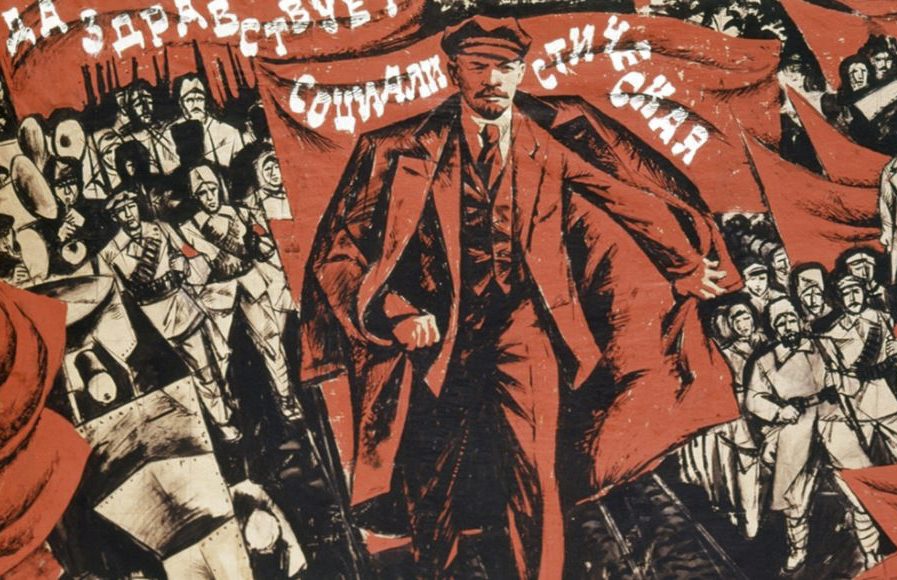

The Russian Revolution

For most people, the term “Russian Revolution” conjures up a popular set of images: demonstrations in Petrograd’s cold February of 1917, greatcoated men in the Petrograd Soviet, Vladimir Lenin addressing the crowds in front of the Finland station, demonstrators dispersed during the July days and the storming of the Winter Palace in October. What happened in the Russian Revolution? These […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.