Reading time: 12 minutes

When the Pacific War began in 1941, Japanese military planners had long recognised that they could not hope to win a protracted war against the United States, its likeliest and likely deadliest opponent in the Pacific. Instead, they pinned their hopes on a swift, devastating series of campaigns to seize strategic points.

By Morgan WR Dunn

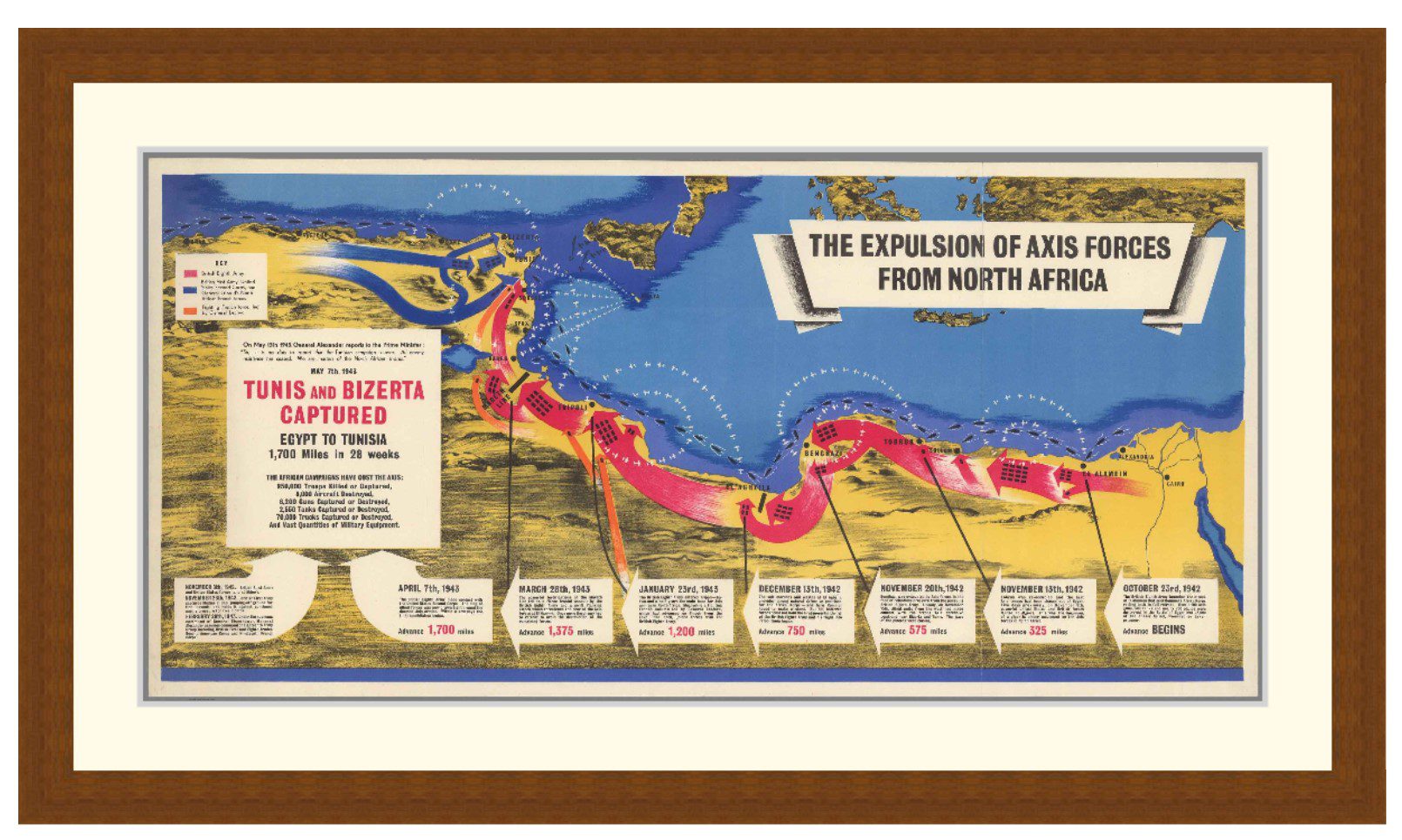

From late 1941 to early 1942 Japanese forces launched simultaneous assaults against Pearl Harbor, Singapore, the Philippines, Guam, the Dutch East Indies, Bali, Timor, Thailand, and New Guinea. Each was selected for the critical resources it contained – especially oil, rubber, and metals – or for the valuable strategic position it occupied.

In the case of New Guinea, control of the island, an Australian-administered possession since 1902, would give the Imperial Japanese Navy control of the Solomon and Bismarck Seas, along with vast reserves of gold, copper, and fossil fuels which could be used to power the Japanese war machine and strengthen its economy. To protect their newly-seized territory, Japanese forces were willing to go to any lengths – including the unprovoked murder of over 60 German and Chinese civilians aboard the destroyer Akikaze.

The Japanese Conquest of New Guinea

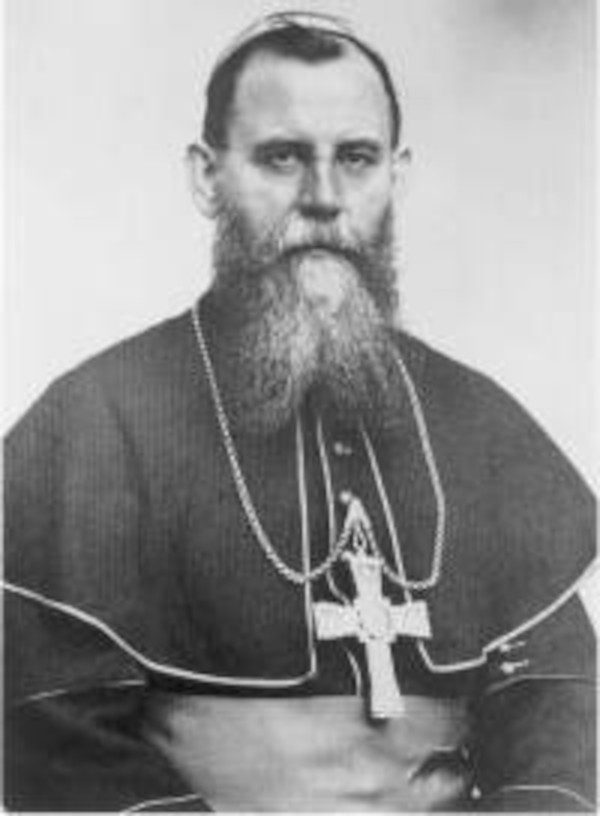

When the Japanese arrived in the Bismarck and Solomon Seas, they found small, scattered, but active communities of foreigners dotted around the islands in those waters. One such community could be found at Wewak, a major town in what had been German New Guinea and seat of the Roman Catholic Apostolic Vicariate of Central New Guinea. Here Bishop Josef Lörks, a German cleric, ran the operations of the church and ministered to the native converts on the island, with the help of about 40 priests, nuns, and their servants.

“For several decades,” writes author Mark Felton, “German missionaries had worked hard not only to convert the locals to Christianity, but they had also endeavoured to improve healthcare facilities for the indigenous tribal peoples, constructing small cottage hospitals and educating local women in child-birthing methods and other health-related issues.” Their efforts had earned them the good will of locals, Australians, and some Japanese alike.

But as representatives of a Western religion, and as potential sympathisers with their fellow Europeans, the Japanese command in the region developed an intense distrust of these missionaries. No one is sure when they decided to resolve this distrust, or who was responsible, but in March 1943, the problem of what to do with these priests and nuns was finally about to be settled.

The Akikaze Receives Orders

Chief Petty Officer Harukichi Ichinose of the 81st Naval Garrison Unit had been a Navy man since 1930. Ichinose was 32 years old when he was ordered to proceed to Lorengau, on Manus Island in northern Papua New Guinea, with a party of 15 men to take over the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) outpost established there in April 1942. Ichinose’s group weren’t the only outsiders on the island: a Christian mission had been in place on Manus for decades, home to 20 foreign nationals dedicated to converting the island’s population.

Ichinose’s war was peaceful, in part, because of his cordial relations with the missionaries. He was neighbourly and graceful, often inviting missionaries to dine with him and maintaining an interest in their welfare. The missionaries, in turn, were peaceable and courteous, and carried out their work as though they’d never heard a war was raging around them.

That’s why it came as such a surprise to Ichinose when, in early March 1943, he received a wireless radio signal from 8 Naval Base Unit in Rabaul instructing him to gather all the missionaries preparatory to their being taken off the island.

At first, Ichinose took his time, assuming the order was low-priority. But when he received a message alerting him to the arrival of a ship to collect the Manus missionaries within two days, he hurriedly sent a messenger around the island to summon them for departure.

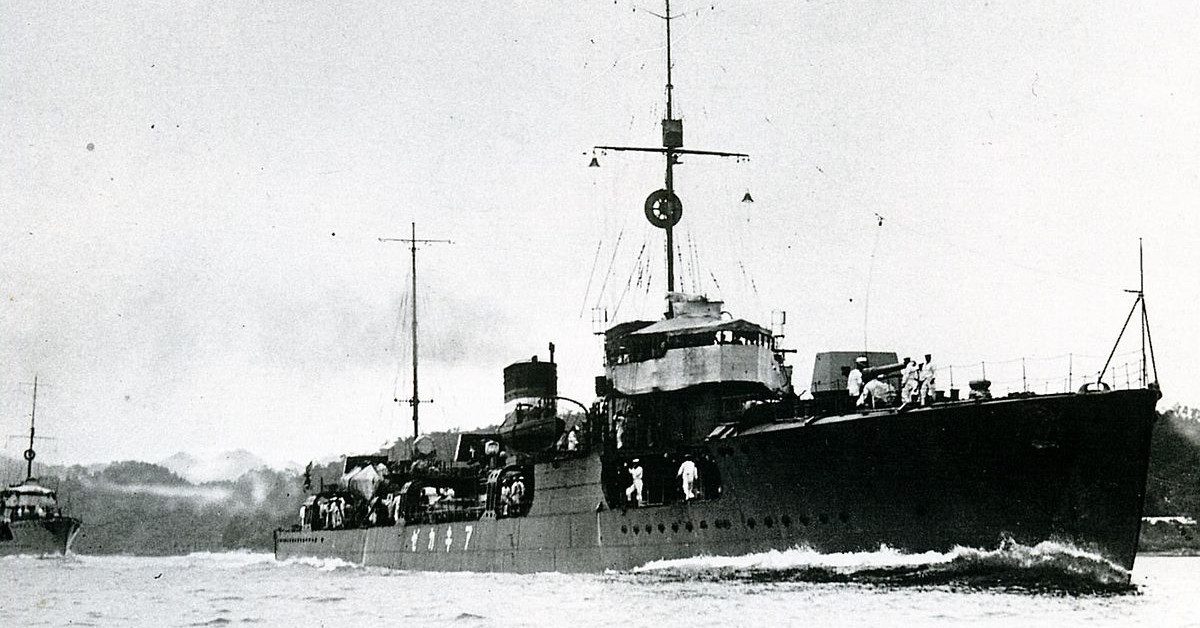

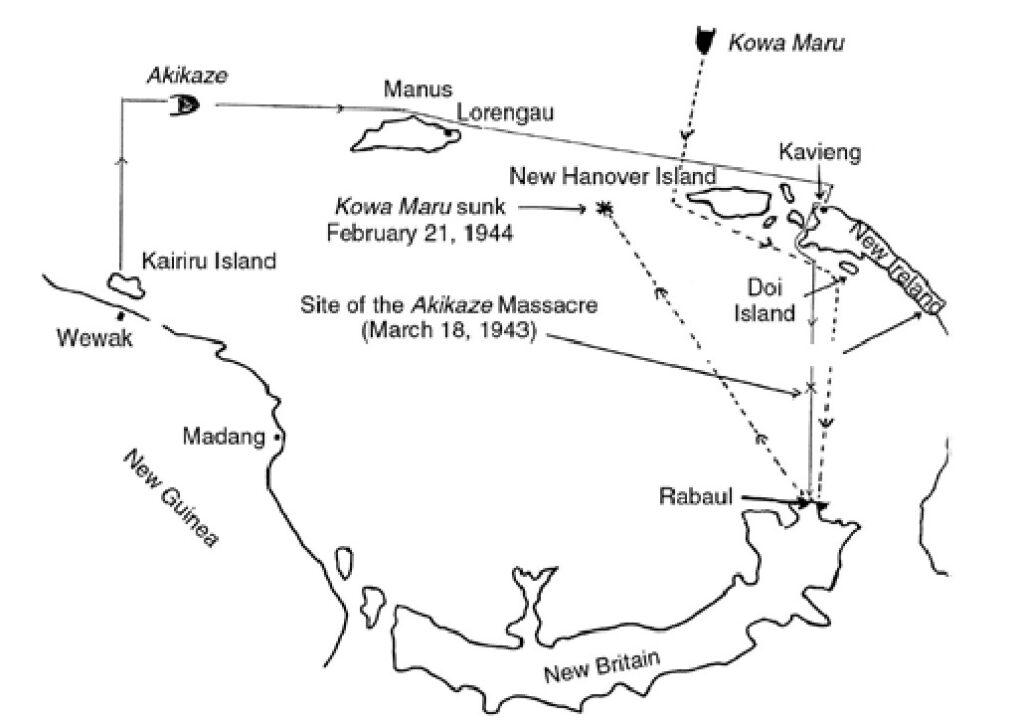

The ship in question was the Akikaze, a 1,215-ton Minekaze-class destroyer built in 1920. Captained by Lieutenant Commander Tsurukichi Sabe, the slightly outdated but still dangerous destroyer was tasked with patrol and supply convoy escort duties in New Guinea’s waters. In March 1943, after delivering food and medicine to the Japanese outpost at Wewak, the Akikaze proceeded to Kairiru, a small island nearby.

There, Captain Sabe took Bishop Lörks and his 40 followers aboard, their removal requested by the 2nd Special Naval Base Force, which saw them as a security threat; downed Allied pilots hiding out in the jungle nearby had attempted to contact the missionaries for aid, and Japanese commanders worried that the missionaries, despite being citizens of an allied nation, might pass on information on Japanese strength and movements.

On the evening of 17th March 1943, Ichinose saw the Manus Island missionaries aboard the Akikaze, asking Captain Sabe to provide more space for them in the crew’s quarters in the aft cabin to avoid overcrowding. Sabe complied.

Once the ship had departed, Japanese troops destroyed every trace of their work, torching clinics and churches and murdering converts. Far on the other side of the world, neither the Vatican nor Germany caught wind of these atrocities, and no complaints were made.

Once aboard, the captive Westerners were treated well, looked after by the ship’s doctor, given bread, tea, and water, and kept safe from air attack below decks. By 11 am on 18th March, the Akikaze dropped anchor outside the port of Kavieng. No one got off; instead, a dispatch boat came out to meet them carrying sealed orders from 8th Fleet Headquarters. Soon after, the ship weighed anchor, sailing south toward Rabaul on the New Guinea mainland.

The Killing

Once at sea, Sabe assembled his officers, including Sublieutenant Kai Yajiro, an interpreter taken aboard at Wewak, and explained the contents of the orders he’d received at Kavieng: the 60 civilians aboard his vessel – the bishop, priests, nuns, Chinese servants, and two Chinese infants – were to be killed. It was regrettable, said the pale and shaken captain, but an order.

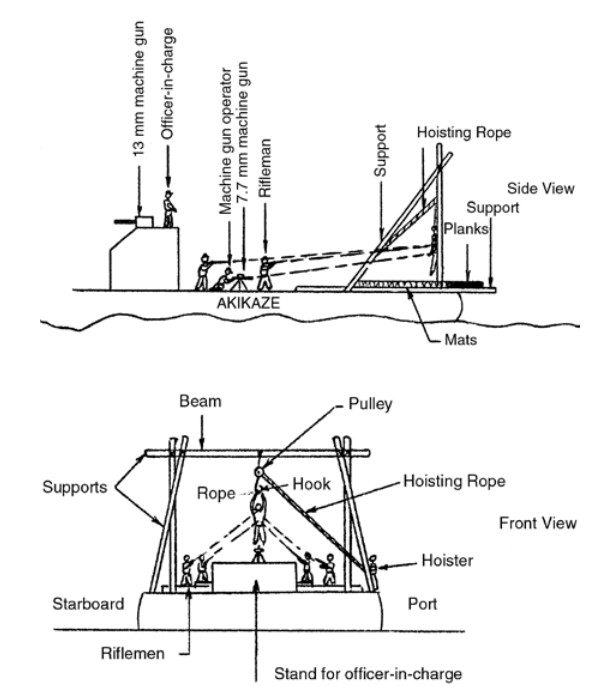

Sabe directed Kai to order the passengers into the forward cabin, supposedly while the aft cabin was cleaned. At the same time, some of the crew were ordered to build a wooden platform at the stern of the ship. The captain ordered the ship to full speed so the noise of the engine, waves, and wind would drown out other sounds.

When the preparations had been made, an officer summoned the male passengers, one at a time, to a spot at the middle of the ship, in front of a large white sheet which had been hung across the ship’s deck. There, they were asked their name, age, nationality, and other details before being ordered aft, behind the sheet.

What they found behind that sheet must have horrified them. A detail under the command of Sublieutenant Terada Takeo blindfolded each passenger, bound their wrists, and strung them from a frame over the wooden platform. A detail of four men using rifles and a machine gun then shot the suspended victim. The lifeless body was then washed overboard by the waves.

When the crew finished with the men, they repeated the process with the nuns and Chinese women. “The two Chinese children,” wrote historian Yuki Tanaka, “were taken from the arms of the nuns and thrown overboard.”

After three hours, all 60 civilians had been killed. The crew washed the blood from the deck and Captain Sabe held a short ceremony to honour the slain passengers. After swearing the crew to strict secrecy, the Akikaze returned to Rabaul on the night of 18th March.

A Postwar Detective Story

But for another investigation into Japanese war crimes, the murders of the missionaries aboard the Akikaze might have gone undiscovered. The ship itself had been torpedoed off Luzon in November 1944, the crew and captain having sacrificed themselves to protect the aircraft carrier Jun’yō. Sabe and Terada had both died in action, and many other officers and sailors who’d served aboard it or in the New Guinea area at the time had also lost their lives as the war drew on.

But at the end of the war, when Australian forces re-established control over New Guinea, they began investigating another massacre, this one involving the murders of Australian civilians and POWs, at the town of Kavieng, the capital of New Ireland.

In the course of this investigation, details began to surface of another group of missing civilians. This time, it was a group of missionaries who’d supposedly been transported away from New Guinea in 1943. The only problem was that no one seemed to be able to find them.

Captain Albert Klestadt, the investigating officer, had spent six years living in Japan, from 1935 until 1941, working in commerce and studying the Japanese language. In May 1943, he joined the Australian Army Intelligence Corps, and when the war ended he was a liaison officer managing the surrender of the Japanese 18th Army.

When the war ended, Klestadt went to work for the Australian War Crimes Section investigating possible Japanese atrocities. It was in this assignment that he caught wind of the vanished missionaries. His team interrogated Rear Admiral Tamura Ryūkichi, commander of the 14th Naval Base Force at Kavieng.

Tamura claimed that 32 (not the 40 indicated by records and other witness testimonies) civilians had been placed aboard the freighter Kowa Maru for transportation to Rabaul. He claimed that they had safely reached Rabaul, and that he did not know their whereabouts after this. With nothing to contradict his account, Tamura was released by Australian authorities in 1946 and repatriated to Japan.

“Tamura’s attitude during his interview, however,” wrote Tanaka, “seems to have aroused the suspicions of the Australian authorities.” Pursuing the inquiry further, they interviewed former crew members of the Akikaze in December 1946 and between January and April 1947. At first, these crew members held fast to Captain Sabe’s orders to keep the killings a secret, but eventually they cracked and revealed the truth.

Upon learning the story of the Akikaze massacre, Klestadt and his team Vice Admiral Mikawa Gunichi, in 1943 commander in chief of the 8th Fleet, to which the Akikaze belonged, and 8th Fleet Headquarters chief of staff Rear Admiral Ōnishi Shinzō. Ōnishi tried to throw the investigators off the scent by claiming the destroyer belonged to the 11th Fleet, not the 8th, while Mikawa claimed that he’d never even heard of the Akikaze. Both men claimed that Lieutenant Kami Shigetoku, an 8th Fleet staff officer, had issued the orders for the killings without approval.

These testimonies didn’t withstand the facts. The Australian investigators knew the composition of the 8th Fleet, and they also understood the command structure of the Imperial Japanese Navy, under which a mere lieutenant could not issue fleet orders without the approval of a senior staff officer. Furthermore, as Klestadt pointed out, even if the two admirals knew nothing of the atrocity, they still bore command responsibility.

The Enigma of Japanese War Crimes

In the end, Australian authorities chose not to prosecute Admirals Ōnishi and Mikawa because none of the victims had been Australian citizens, and because with all the men involved being dead, no one was left to contradict the admirals’ claims. Some had, however, been United States citizens, so the case was handed over to American authorities. Still no prosecution materialised, in all likelihood because this was just one of far too many similar cases to bring to trial. There were more instances of Japanese war crimes and atrocities than either Australia or the US had time, resources, or political willingness to pursue. Although they would at least be known, the victims of the Akikaze massacre would not receive justice.

What made the murder of the missionaries in the Solomon Sea unique was not that they were alone, but that the perpetrators were regular forces. German forces committed innumerable war crimes between 1939 and 1945, and while regular military forces were guilty in some of these cases, the murder of civilians was often entrusted to specialised death squads such as the Einsatzgruppen or units of the SS. In the Japanese Empire, these atrocities were carried out not by such dedicated killers, specially equipped and prepared for the task, but by ordinary men soldiers and sailors like Lt. Cmdr. Sabe and his crew.

Today, no memorial exists for the 60 men, women, and children coldly killed at sea aboard the Akikaze. Mikawa Gunichi and Ōnishi Shinzō both lived into their 90s, dying peacefully in Japan.

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 186

1. When did the Spanish Inquisition begin?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

General History Quiz 62

Weekly 10 Question History Quiz.

See how your history knowledge stacks up!

General History Quiz 183

1. Which mathematician fought against the Romans to defend the city of Syracuse?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.