Reading time: 5 minutes

Alexander the Great was a successful conqueror, but a poor planner. He died without an acceptable heir to inherit the empire, just a soon-to-be-born baby son, and a half-brother not quite up to the task.

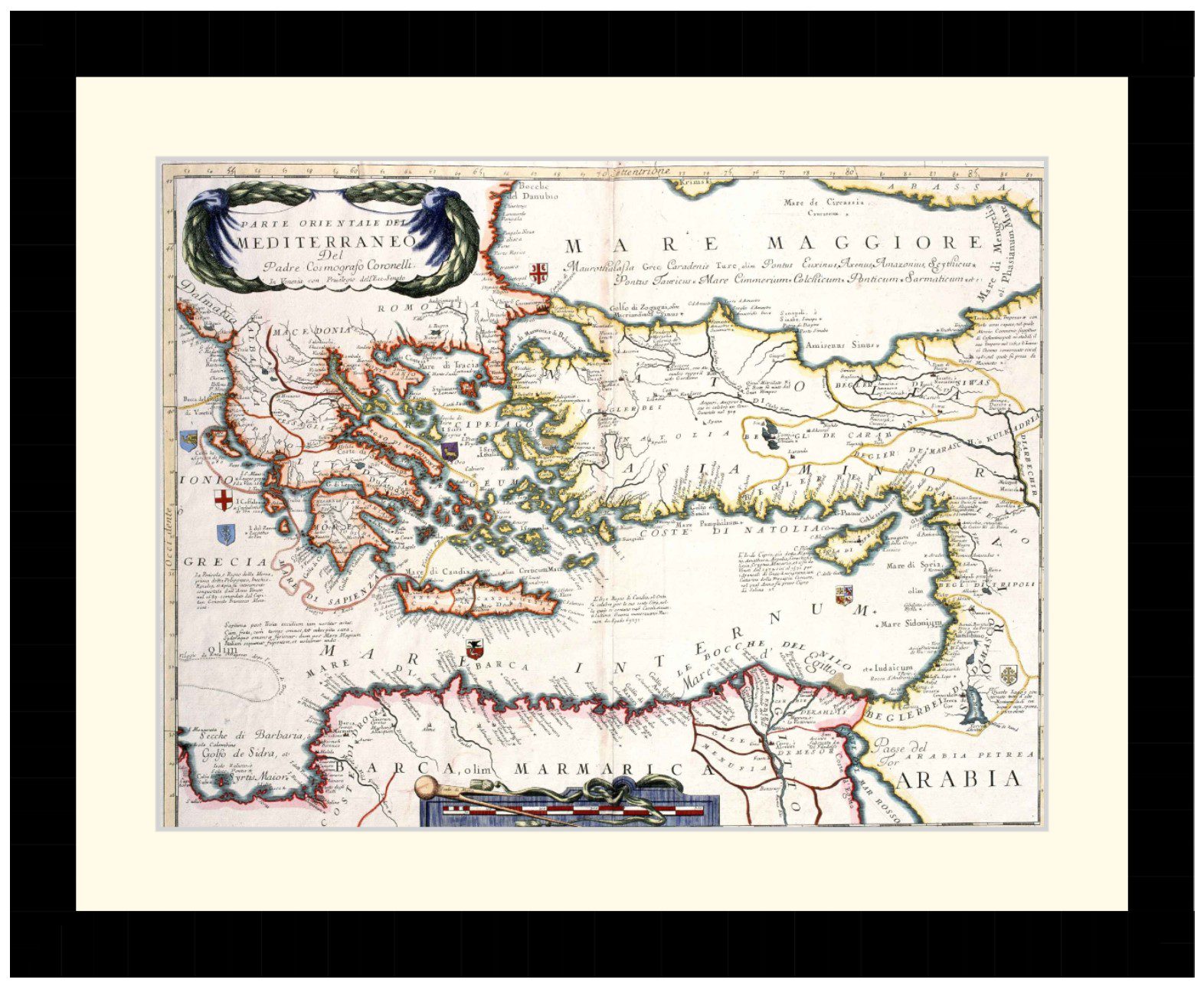

And as Game of Thrones fans will know, such circumstances can lead to quite the power struggle, with poisoning plots, dramatic marriages, incest and a whole lot of fighting. We find all this and more in the Hellenistic Age, which is what we call the time period 323 BCE-31 BCE, starting with Alexander’s death and ending with Cleopatra’s famous snake bite.

By Charlotte Dunn, University of Tasmania.

These circumstances began the career of Demetrius the Besieger, one of the more outrageous rulers of the time. Like many others who fought for a piece of Alexander the Great’s empire, Demetrius was never supposed to be king. But he and his father Antigonus the One-Eyed didn’t let a lack of royal blood get in the way of ambition. The two of them spent many years fighting, stealing territory, and eliminating rivals.

In 306 BCE, they both claimed the title King. They were trendsetters in this area, and soon self-made kings popped up all over the place, dividing Alexander’s empire into smaller kingdoms of their own. But even during this time of royally bad behaviour and a multitude of rival kings, Demetrius still managed to gain a standout reputation.

Work hard, play harder

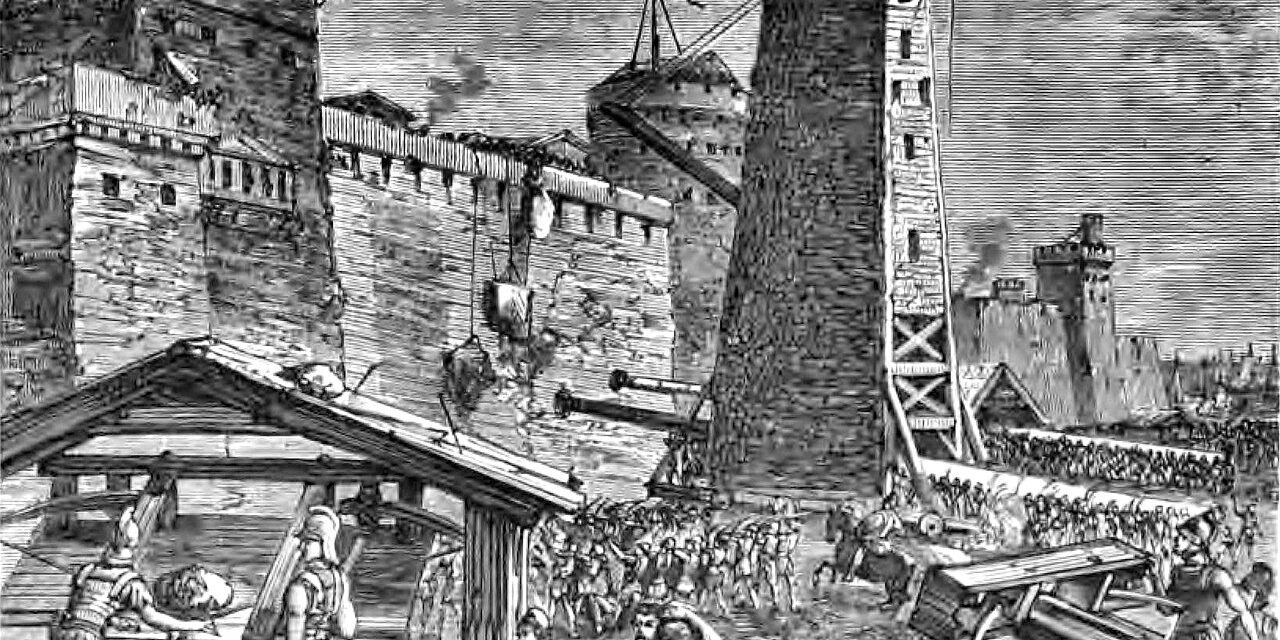

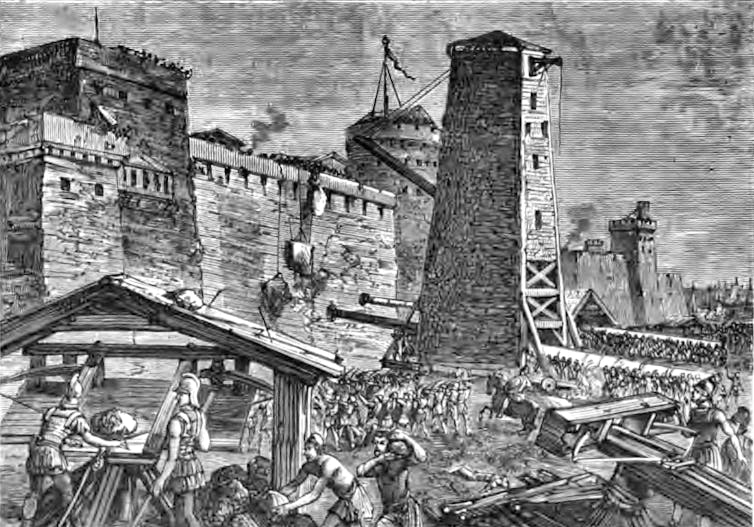

Demetrius’ biographer, the ancient author Plutarch, tells us Demetrius had a policy akin to work hard and play harder. He was famous for his ingenuity and extravagance when it came to siege equipment and his skill in this type of warfare earned him the name Besieger.

His repertoire included the use of a monstrosity called the Helepolis (city-taker), a type of mobile tower block estimated to be between 30-40 metres tall, with a base of 21 metres.

This terrifying creation was filled with soldiers, and would screech as it moved slowly towards its target city. This was such an amazing sight that, according to Plutarch, even those under siege had to admit they were impressed.

Coins and calendars

It can be difficult to tell fact from fiction in history, and the ancient writers certainly tell us some strange stories about Demetrius.

He is said to have manipulated time by changing around the calendar months, all so that he could complete his initiation into the Mysteries (a religious cult) faster than was legal.

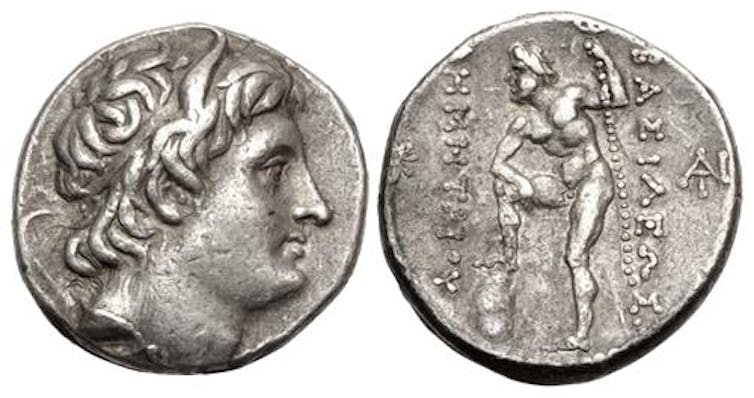

He put his own portrait on his coins, and was probably the first living person to do so in the western world. Before this audacious move, the heads side of the coin had normally been reserved for images of gods or honouring important (deceased) individuals.

The Athenians even ended up addressing Demetrius as a living god in a special hymn, calling him the son of Poseidon and Aphrodite.

Parties and polygamy

Demetrius’ partying earned him an even more notorious reputation.

He had a handful of wives (Demetrius was a polygamous king, and ended up marrying at least five women), but his favourite companion was the courtesan Lamia, whose name refers to a flesh devouring monster.

There are plenty of tales of the two of them cavorting together, sometimes rather sacrilegiously. For example, the Athenians tried to honour Demetrius by allowing him a symbolic marriage to their patron goddess Athena – but the Besieger didn’t think too much of marrying a statue. Instead, he and Lamia went into the temple and committed various acts said to be rather shocking to the virgin goddess.

Demetrius is even accused of taxing the city 250 talents (about 6,000 kilos of silver or gold), only to turn it over to Lamia and his other mistresses so they could buy beauty products.

Popularity and public relations

All this irreverent behaviour can only take you so far. Kingship, like many careers, requires a certain amount of admin work. Demetrius’ Macedonian subjects were dismayed by the disinterest of their king, but on one occasion they gained a little hope.

Demetrius actually took their petitions as though he intended to read them. They followed the king along on his walk in great excitement, only to watch in horror as Demetrius then dumped all of the petitions over a bridge, into the river below.

He was run out of Macedonia a little while later, ancient evidence of the importance of public relations. This sort of reversal of fortune was something Demetrius was well-versed in, having won and lost many times over throughout his career. So he simply went on with campaigning until he was deserted, broke, and fell into the hands of one of his enemies.

It was a sorry end for such a colourful character, but during his captivity Demetrius applied himself as vigorously to leisure and drinking as he once had to besieging and love affairs. He might not have kept his throne, but he certainly earned his place in history, an outrageous and fascinating individual, and truly a king.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Articles you may also like

When Australia Fought France, WWII – Video

Operation Exporter was a little known, but very important campaign for the Australian military. It involved Australian’s fighting a strange war against confused Frenchmen who were not supposed to be our enemy. France had been defeated and subjugated by the Germans. The new French government, installed at Vichy, was answerable to the Führer. With France vanquished, the fate of their territories in Syria and Lebanon became uncertain.

Traitors to King and Country: Inside the British Free Corps, Hitler’s British Legion

Reading time: 11 minutes

From the moment it took power, the Nazis ruled over a German state possessed of two armies. One was the inheritor of the imperial lineage of the First World War, and the second was the Waffen-SS, which grew from a tiny band of Hitler’s most hardened antisemites to a force of nearly a million men from over two dozen nations before its demise.

How German PoWs staged their greatest World War I escape from a camp now part of a British university

Reading time: 5 minutes

Escape was a romantic ideal rather than a rational expectation. Gunter Pluschow, who escaped from another PoW camp at Donington Hall, in Leicestershire, was the only German to make it home in World War I, largely because he managed to adopt a disguise and stow away on board a cargo ship at Harwich.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.