Reading time: 8 minutes

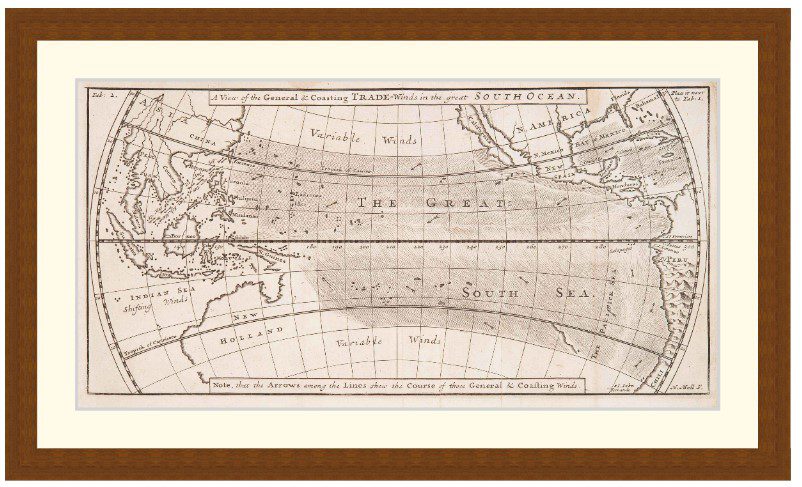

Huge ships filled with canons, gold, porcelain, silk, and other riches from Asia, the Manila Galleons were the key vessels in transporting rare goods from Asia across the Pacific Ocean to Spanish holdings in Mexico. From there, the cargo could easily be sailed across the Atlantic to Spain and Europe.

Despite their huge size, and their importance in bringing wealth into Spain, the Manila Galleons are most famous for one thing: sinking.

By Mark Mckenzie.

But why? Why did the best ships Spain could construct, carrying some of the most precious cargo in the empire, seem to shipwreck so often?

And not just a little bit more than usual – according to economists Arteaga, Desierto and Koyama roughly 20% of the Galleons travelling from Manila to Mexico shipwrecked, more than four times as many as other routes, such as the Dutch East India trading route, which suffered a shipwreck rate of only 3.5% of ships.

The Start of Globalisation

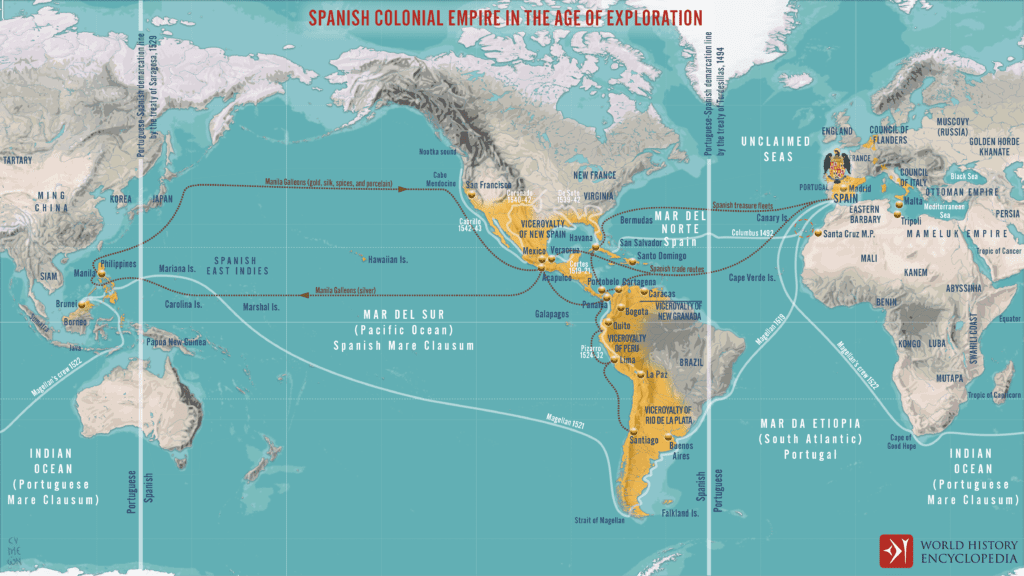

Though disputed, many historians argue that the first stage of globalization began in the 1400s to 1600s alongside the age of discovery, and in this period of colonization the Manila Galleon trade route was a vital lifeline to Spanish territory in Asia, as well as a sizable source of income for the Empire and private Spanish merchants.

In a time when the Spanish, Dutch, and Portuguese had already established vast trading outposts across the world, and the British and French empires were rapidly asserting themselves on the global oceans, maintaining stable trade routes was as important as ever to the Spanish.

The Manila Galleons served as a crucial link between the colonies in the Philippines and Mexico, as the route enabled the exchange of valuable commodities both ways: Asian goods flowing into the Americas and silver from Mexican mines being used to facilitate this trade.

More Than Just A Lucrative Trade Route

This cycle of commerce not only generated substantial wealth for the Spanish Empire, it also solidified its global economic dominance. Control over the Manila Galleon route provided Spain with strategic advantages, being able to regulate trade from China into Europe.

Typically sailing only once a year, and occasionally twice, the colony of Manila came to rely heavily on the arrival of the Manila Galleon.

Its arrival, bringing gold and silver from Mexico and allowing local merchants to sell their lucrative Chinese goods to Europe was so important that when a ship did not arrive, the entire colony would be plunged into economic depression.

Until the 18th Century when other European powers entered the picture, the Spanish hold in Manila and the Philippines remained one of Europe’s primary links to China, strengthening Spain’s geopolitical influence in the Pacific.

To get some idea of just how much money was circulated on this trade route, 3 to 5 million silver pesos were shipped annually from Mexico to Manila, equating to about one-third of all the silver and gold mined and minted in the Spanish New World.

Famous Shipwrecks

Of roughly 130 lost Manila Galleons across several hundred years, around 100 have been found near the Strait of San Bernardino in the Philippines, with only four captured by the British, and some others being sunk by the Dutch during various warring periods.

While there are several famous Manila Galleon shipwrecks, three notable ones include the Nuestra Señora de Atocha, the San Diego, and the Santa Rosa. Each wreck carried a significant amount of cargo, with the goods inside the Atocha being valued at around $400 million.

Each wreck typically contained a vast assortment of goods, including silver bars and coins, gold, precious gemstones and metals, cultural and religious artefacts, Chinese porcelain, silk, ivory, spices, and other textiles.

Why Did the Manila Galleons Shipwreck so often?

When your most valuable ships are sinking four times more often than everyone else’s, something must have gone wrong.

For a long time, the high rate of shipwrecks for the Manila Galleons was a bit of a historical mystery – given that every other European empire faced similar issues of stormy weather, difficult navigation, and privateers, why was it Spain’s Manila Galleons that sunk and shipwrecked so much?

Well in 2020, economists and historians Fernando Arteaga, Desiree Desierto and Mark Koyama published their paper Shipwrecked by Rents, finally revealing the truth behind why the Manila Galleons couldn’t stop sinking.

16th Century Lobbying

The first thing identified is how much Spanish merchants back home did NOT want too much trade coming in from Manila. More ships meant even more high-quality silk and porcelain that European merchants couldn’t compete with.

So of course, these merchants lobbied the Spanish Crown to reduce the number of shipments per year. Although this sort of protectionism would negatively affect the Spanish Empire in the long run, in the short-term this protectionism ensured that Manila Galleons made an even higher profit due to the laws of supply and demand.

This lobbying is the main reason why only one or sometimes two convoys sailed to and from Manila each year, despite how many riches the colony had on offer to transport. With too many goods and not enough cargo room, the next issue arose.

No Risk, No Reward

Easily the largest ships on the seas at the time weighing in at roughly 2,000 tons – around 500 tons heavier than their Atlantic counterparts, Manila Galleons (built in the Philippines) were specifically designed to haul as much treasure as possible.

But with only a few ships arriving each year, there was not nearly enough cargo room for all the merchants and goods in Manila – especially if you were looking at a 200% profit margin on a successful trip.

To regulate the trade, the Spanish crown had introduced rules and systems – ships had to sail before mid-July to avoid monsoon season, they couldn’t exceed their cargo limit, and allocation of cargo space was based on a ticket system.

For most other shipping lanes in the world, there was no such restriction of one voyage a year – so if you couldn’t get a slot on the first ship, why not wait for the next one? But in Manila, missing out on a voyage meant a year’s wait at best.

Because of this, bending the rules was a much more appealing prospect.

Small Salary, Big Bribes

The captain of each Manila Galleon was on a pretty measly salary, given the valuable goods they were transporting. They were mostly paid via the default allocation of one ticket for themselves.

They also were in charge of the ticket system, and enforcing the rules of the Spanish crown.

This is opened the door to corruption and bribery. Looking at the ship’s logs of found wrecks of Manila Galleons, most seem to leave after the cut-off date of mid-July, willingly sailing during the treacherous Monsoon season, and now the reason to take that risk is revealed.

With low pay and all the power, Captains of each Galleon were practically incentivised to take bribes, overloading their ships with extra cargo, and leaving later than intended as it took time to load up the ship.

In fact, many of the wrecked ships were found to be carrying up to four times the legal limit! And given that the Captain could afford to retire from a single voyage based entirely on the bribes, the risk of sailing during Monsoon season likely seemed like one worth taking.

As with many things, it was a combination of everyone involved that led to the huge number of wrecked Manila Galleons. From the Captain who took bribes, to the merchants who were desperate to get their cargo onto the ships, and the Spanish Crown only allowing one ship per year, along with the treacherous weather of Monsoon season.

Podcasts about the Manila Galleons

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 210

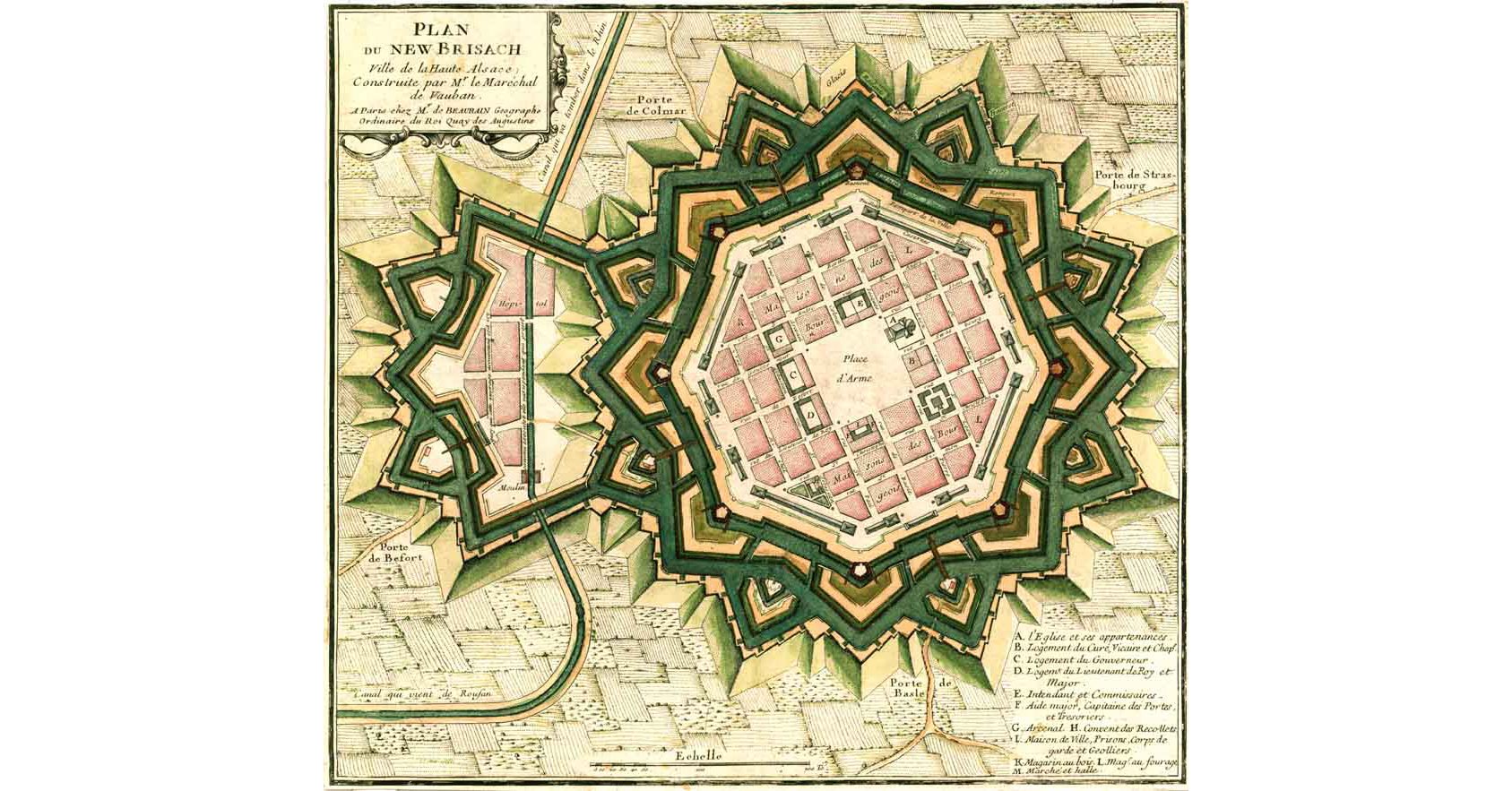

1. Who was Europe’s most prolific military engineer, creating over 150 fortresses?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The first photograph of the entire globe: 50 years on, Blue Marble still inspires

Reading time: 6 minutes

December 7 marks the 50-year anniversary of the Blue Marble photograph. The crew of NASA’s Apollo 17 spacecraft – the last manned mission to the Moon – took a photograph of Earth and changed the way we visualised our planet forever. Taken with a Hasselblad film camera, it was the first photograph taken of the whole round Earth and is believed to be the most reproduced image of all time. Up until this point, our view of ourselves had been disconnected and fragmented: there was no way to visualise the planet in its entirety.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.