Reading time: 5 minutes

If sometimes it seems that governments rush to appoint inquiries or royal commissions, then I want to assure you: this is no modern-day phenomenon.

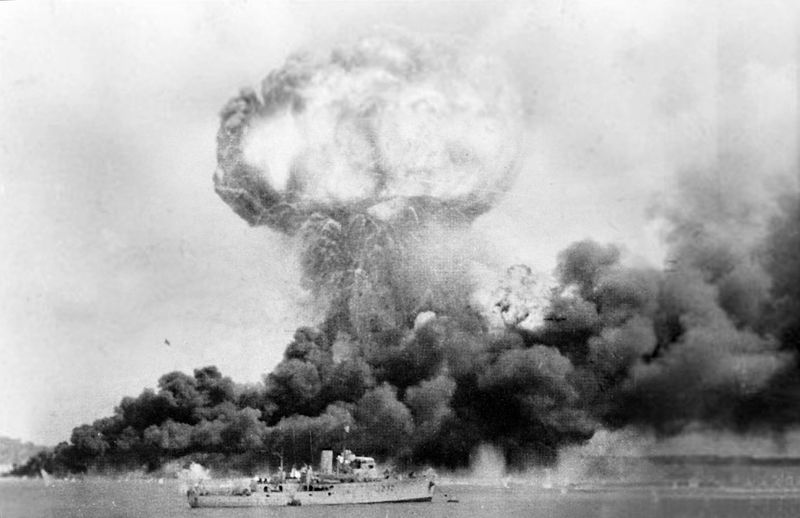

The bombing of Darwin, on this day 79 years ago, prompted a swift response from the Commonwealth. On 3 March 1942, Justice Charles Lowe, a Victorian Supreme Court judge, was appointed to conduct a commission of inquiry into the events of 19 February.

Lowe acted with great haste and, in the early hours of the following morning, 4 March, just two weeks after the bombing, he was on a plane to Darwin to begin his inquiry.

And he quickly gained great personal insights—the Royal Australian Air Force’s Darwin airfield was bombed at 2 pm on the day of his arrival.

The purpose of Lowe’s inquiry was to report on the damage sustained, the number of casualties, the degree of cooperation between the armed services, the steps taken to defend the town, whether military and civilian commanders failed to discharge their responsibilities, and the level of the preparedness of military and civil authorities.

However, something quite critical was missing from his terms of reference. That is, what steps had the Commonwealth government taken to ensure that Darwin was properly protected in the first place?

Certainly, it was fair to ask whether the military leaders in Darwin had done enough. However, they could work only with the tools they were given. And those very few tools were given to them by the Commonwealth.

Darwin was desperately underprepared for what occurred on 19 February 1942.

Lowe, however, would not need to level any criticism at the Commonwealth in his report, because it was conveniently exempted from his line of inquiry.

Of course, we know that even before this, the first attack on Australian soil, our service people were already stretched in places near and far.

We were in France and Italy, the Mediterranean and North Africa, and Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Singapore had fallen days before, leading to the horrific enslavement of 15,000 Australian personnel.

But everyone—that is, everyone in senior political and military positions—knew that an attack on Darwin was coming. And yet the city had no functioning radar. Darwin’s early warning system was what locals could see in the sky with their own eyes.

Japanese observation aircraft were seen flying over Darwin in the days immediately prior to the attacks. An American freighter came under attack on the Wessel Islands off Arnhem Land the day before. A Japanese aircraft carrier was observed lurking in the Flores Sea.

These were heavy hints.

At the time, a young woman named Betty Page had a job with military intelligence censoring all mail that left Darwin, cutting out the parts of letters that might have told of boats on the harbour, movements of troops or, really, anything that described life in Darwin.

Page (later Duke) recalled in a 1992 interview with the Northern Territory Archives Service that by the time she’d finished cutting out the problematic parts of letters, they went back into the envelope looking like paper lace.

The authorities took those measures because they knew the threat to Darwin was real.

Even so, Page, who undertook secretarial duties in an office with excellent insights into the coming storm of terror, was not ready for it.

No one was.

On 19 February, she heard the planes and said to a colleague: ‘Oh, isn’t it lovely, the Americans are arriving.’ Then the bombs started falling.

Page, putting on her tin hat and carrying her first-aid kit, rushed out to help people who had been hurt.

Just 200 metres from the Darwin Cenotaph War Memorial, near the old Hotel Darwin site, a bomb landed and Page was flung, concussed, to the ground. She got up and kept helping the injured, not realising that she herself was badly wounded by shrapnel.

She was taken to hospital but had to run when it was hit in the second raid.

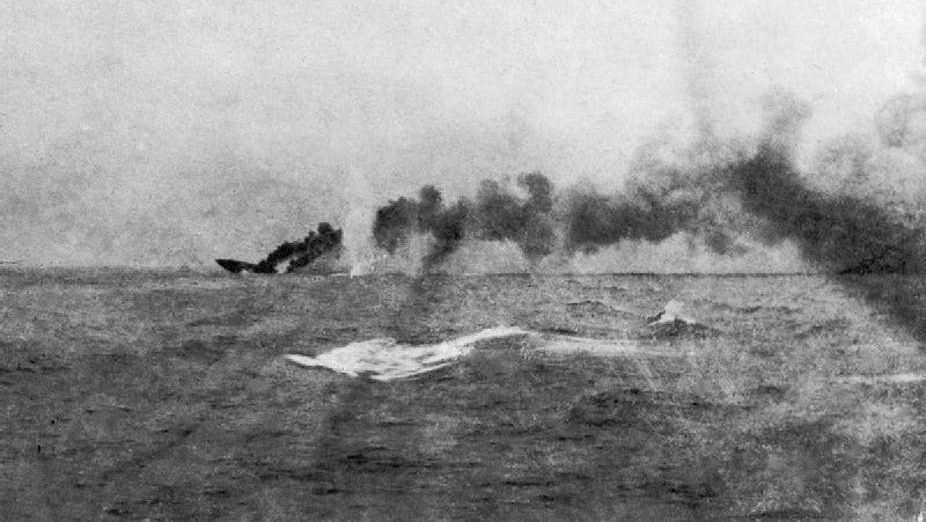

Darwin took a terrible toll that day.

And we are entitled to ask: are we any better defended all these years on?

I think the answer to that is yes.

One of the constants of politics is that our national leaders, who are responsible for our country’s defence, have to strike a balance between the requirement to spend money on war craft as a form of insurance and the very real need to satisfy the everyday demands of the population.

We, as a people, would surely much rather go about the business of building roads, hospitals and schools ahead of buying weapons and building defences that may never be used. And Covid-19 has shown us that we need to dig deep into our nation’s cash resources to keep the country moving.

But the experience of Darwin in 1942 has taught us that we can never rely on hope as a deterrent.

We now have long-range radar guarding the north. We’re about to have a squadron of F-35 fighter jets at RAAF Base Tindal. Our navy is positioning new vessels here. We are moving fast into the era of unmanned defences, our training ranges are the world’s best and our alliances are strong.

And, of course, old enemies are now the closest of friends, and that is particularly evident in Darwin, with Japan being a major trade partner through the Ichthys LNG project and taking a presence in our skies with joint exercises.

But we do know that one thing has not changed since 1942. Darwin is critical to Australia’s forward defence and integral to our national security. Geography will always matter and Darwin remains Australia’s watchtower in the Indo-Pacific.

That is why we hold close the events of 19 February.

Here, in Darwin, we do not forget. Not ever. It is not because we glorify war. It is not because we are on the alert for imminent attack. There is no threat ringing in our ears as we go about our daily business.

This day reminds us that Darwin, and indeed the entire north of Australia, play an important role in the security and prosperity of this nation.

It was true then, and it is true now.

And it is only by remembering that we can truly say: lest we forget.

This article was originally published in The Strategist.

Articles you may also be interested in

General History Quiz 71

Weekly 10 Question History Quiz.

See how your history knowledge stacks up!

1. What aircraft is this?

Australia’s first action in the Pacific in World War II a valiant catastrophe

Just before midnight on 7 December 1941, Flying Officer Peter Gibbes stepped off the train at Kota Bharu on the coast of northeast Malaya after a long, tiring journey up the peninsula from Singapore. Gibbes, an airline pilot in peacetime, had been newly posted to the Royal Australian Air Force’s 1 Squadron, which in the […]

Defences of Australia – 19th Century

Modern Australia is relatively unique in it’s position occupying an entire continent, having no land borders with another country. While this provides assurance against a purely land based attack, the 60,000 km coastline offers many opportunities for seaborne invasion. In the 19th century there was a significant fear of invasion by Britain’s enemies, with over […]