Reading time: 10 minutes

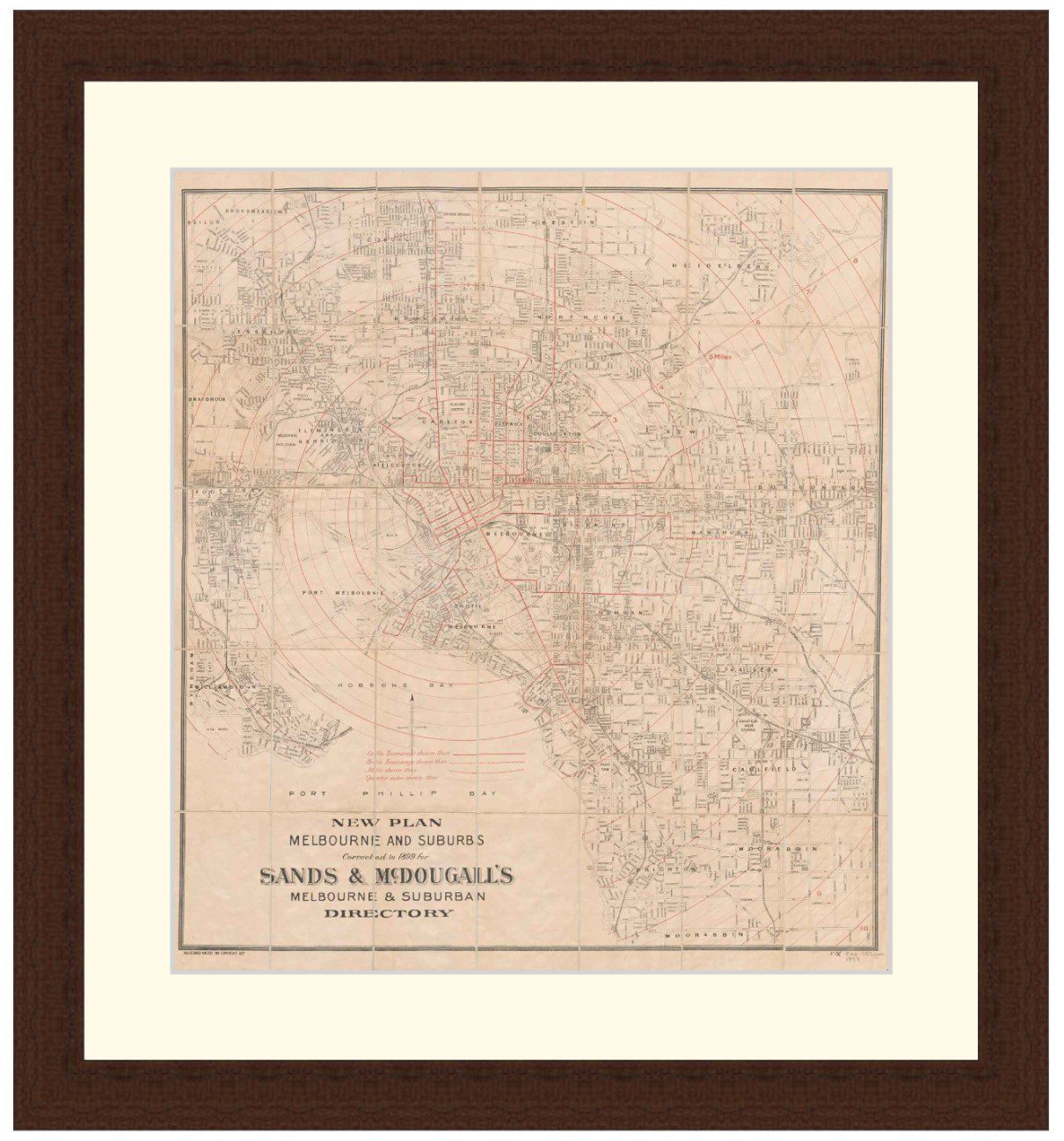

William Stott was born in Manchester, England, in 1909. He came to Australia in 1928 as part of a young farmers program, working on sheep stations in the Riverina before moving to Bonnyrigg, NSW. He and a friend established their own farm here, which William worked until war was declared in 1939. William gave up his share of the farm to his mate and enlisted. He was 30 years old when the Second World War broke out – he enlisted immediately. Bonnyrigg is now a suburban part of Western Sydney, it was then then a rural farming area. On 7th November 1939, William began his training as a member of the 2/1st Australian Infantry Battalion, which was part of the 16th Brigade of the 6th Australian Division. The 2/1st Infantry Battalion departed from Sydney aboard the SS Orford, designated as His Majesty’s Australian Transport (HMAT) U5, on 10th January 1940. The convoy arrived in Kantara, Egypt, on 13th February 1940, and William then moved with his unit to Palestine for further training.

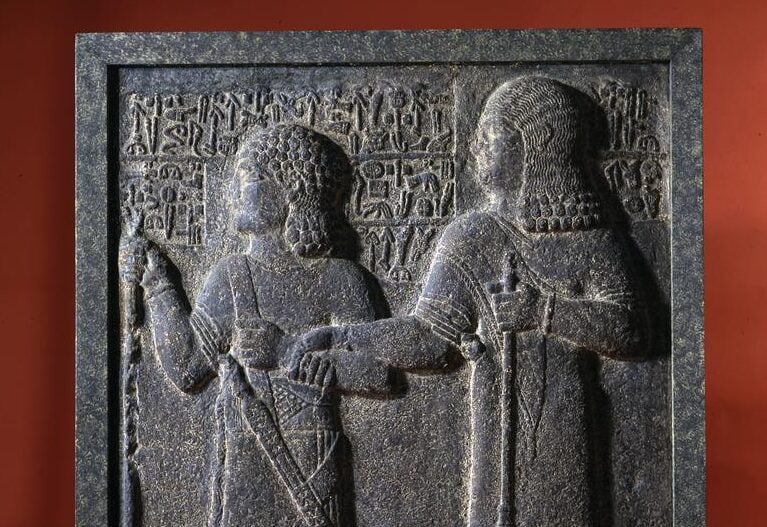

In the first week of 1941, around 15,000 Australian troops, supported by at most 1,500 British troops, attacked 45,000 Italians at Bardia. The 2/1st was assigned to breach the Italian defensive lines around Bardia, which were fortified with trenches, barbed wire, and concrete bunkers. Here, William saw combat in spectacular fashion, in what is considered by most to be the first significant Allied victory on land of World War II.

Towards the end of January 1941, Australian forces repeated their success at the First Battle of Tobruk. William once again fought and shared in the victory. By the time Axis forces besieged Tobruk in April, in what would be known as the Second Battle of Tobruk, William was already elsewhere. The 2/1st Infantry Battalion had departed the Middle East on a troopship on 18th March 1941, as part of the Allied efforts to defend Greece from the advancing German invasion.

In early April 1941, the 2/1st Infantry Battalion participated in the defence of the Mount Olympus region and later in the Battle of Brallos Pass. These were crucial defensive positions, as they were narrow passes through mountainous terrain, which the Allies hoped to use to delay the German advance. The 2/1st Battalion fought hard against the German onslaught but was eventually forced to retreat, as the Wehrmacht proved to be far better armed and motivated than their Italian allies in North Africa. After having to fight against a more numerous, better-armoured, and better-supported German army, William was now forced to retreat with his unit, constantly under attack from dive-bombers and paratroopers.

Visit the Brallos Pass Battlefield

While hundreds died and thousands were taken prisoner during the evacuation, William was lucky to be among those tens of thousands who managed to leave from Piraeus (Athens) to Crete. There, he would take part in the Battle of Crete in May 1941, defending against the German airborne invasion. The 2/1st and 2/11th Battalions were the defenders of Rethimno, their fierce fighting was considered to be ‘Unsurpassed in the Annals of Australian Arms’ . This time William’s luck had run out, and on 30th May 1941, he was injured by a hand grenade and subsequently captured near Rethimno.

Visit The Rethimno Battlefield

On 12th June 1941 his unit listed him as missing. His friends in Australia likely heard about it on 24th or 25th July when both The Daily Telegraph and The Sun had Private William Stott listed as missing. In the records, William had listed his mother, Charlotte Stott, who lived in Manchester (UK), as the next of kin, so presumably the AIF had notified her by telegram. At this time, missing William was being held as a prisoner of war (POW) in Kokkinia hospital in Greece, where he was being treated for his combat wounds.

On 4th September 1941, William was transferred to the German POW camp Stalag VIII-B, located near the village of Lamsdorf (now Lambinowice, Poland) in Silesia. Here, he described the living conditions simply as ‘bad.’ He noted that they lived in ‘overcrowded huts’ with electric lighting and poor heating. Food rations were described as ‘bad’ and of ‘poor’ quantity. The food was so bad that a number of Allied POWs at the camp, including William, went on strike from they work the Germans required them to do. However this attempt was unsuccessful, and the strikers were severely punished. William stated that the camp sanitary facilities were ‘bad,’ but that bathing and washing were ‘fair.’ As for clothing, he stated that all that was issued was ‘British battle dress, sent by the Red Cross.’

Labour was paid 70 pfennigs per day, with work including stone quarry work for 9 hours a day, or farming for 12 hours a day, both 6-7 days per week. Surprisingly, it would seem that in terms of entertainment, the camp did fairly well, as William described that sport, entertainment, and reading (including camp newspapers) were readily available, ‘all Red Cross stuff.’ He received mail regularly.

In addition to being treated for his combat wounds in Greece, William was also treated for nephritis in Lamsdorf prison hospital. This treatment took place from 24th October 1941 to 20th March 1942, and apparently the condition was not fully resolved, as William had to return to hospital from 29th April to 27th May 1943. He said that the treatment in hospital was fair, but that shortages in medical supplies were noticeable. As for the general treatment by the guards, William noted that it was harsh in 1941-42, but that it improved later in the war.

William was released by the Germans prior to the end of the war. This was part of a program administered by the Red Cross, which allowed for POWs who were injured to the extent that they would no longer be able to contribute to the war effort to be exchanged. In William’s case this was facilitated through Switzerland, with Red Cross officials visiting the POWs to verify the legitimacy of their injury. Once verified they went by train to Switzerland, then to France, and finally by Hospital ship to the UK.

On 1st February 1945, William disembarked in Liverpool, UK. By 12th February, he was visiting his family in Manchester. After recuperating in Britain, William embarked for his homeland and disembarked in Sydney on 23rd May 1945. His Army Service Record has ‘Repat POW Can Not Be Employed on Active Military Service’ written in red pen in several prominent places. This was to ensure Australia complied with the terms of his release from German captivity.

A year later, he was officially out of uniform. Private William Stott had served for 2,098 days, of which 1,961 were spent outside Australia. At the time of repatriation he was 36 years old. For his service, William received several medals, including the Defence Medal, the War Medal 1939/45, the Australian Service Medal 1939/45, and the Africa Star with the First Army Clasp. That he was proud of his service is evident from the report that he requested his “Returned from Active Service Badge” to be replaced after it fell off his coat in Liverpool in 1979 and was lost.

In 1946 William married Marjorie Mary Honey, who had served in the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force during the war. Prior to the war Marjorie had been a dressmaker. She enlisted in 1943, initially training as a wireless operator. After nine months in this role the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force decided to take advantage of her experience and she re-mustered as a ‘Tailoress’. She served ably in this role, being recommended for promotion and reclassification in 1945. However by this stage the war was drawing to a close, and she was discharged as a Aircraftwoman on 30th November 1945.

William and Marjorie initially lived in Glebe, before moving to Bonnyrigg, where they established a poultry farm. They had four children, who remember William as a hard worker and a wonderful father. William lived on the property in Bonnyrigg until his death on 31st August 1985.

William is commemorated on the Ballarat Australian Ex-Prisoners of War Memorial.

Articles you may also like

Weekly History Quiz No.290

1. How many ships did the Battleship Bismarck sink?

Try the full 10 question quiz.