Reading time: 6 minutes

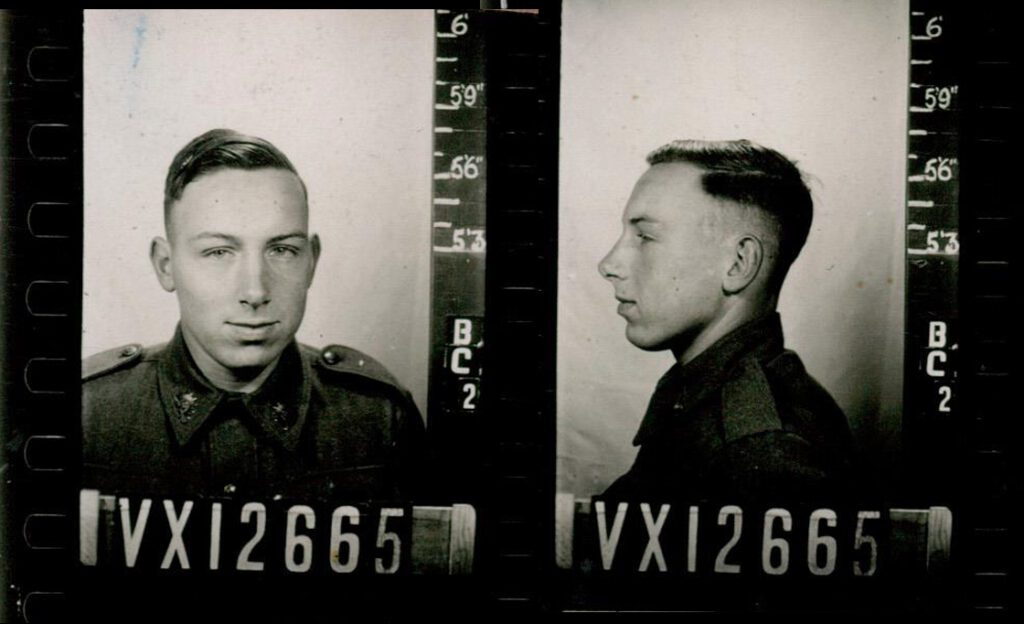

Donald Christie was born in Warrnambool in 1918, during the last summer of the Great War. By the time the Second World War began, he was a farm labourer in Brunswick. On 9th April 1940, at 21 years of age, Donald enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). Barely more than a month after he started training, Donald was already aboard a ship heading to the Middle East, where he would continue his training as a private in the 2/6th Australian Infantry Battalion.

2/6th Australian Infantry Battalion

In October 1940, Donald fell ill to the point that he needed to be hospitalised. Although it was an unpleasant experience, to be sure, it was far from uncommon for soldiers’ immune systems to suffer due to the extreme change in living conditions. By January 1941, however, he was back on his feet when the 2/6th Battalion joined the Battle of Bardia. It was the first major victory for Australian forces in World War II and paved the way for further advances against the Italian army in North Africa. Originally, the battalion was tasked with a diversionary attack to draw Italian attention away from the main assault. However, due to a series of misunderstandings and miscommunications, the 2/6th found themselves in the thick of the fighting, facing fierce resistance from well-entrenched Italian positions. In the process, they lost 22 soldiers, while over 50 were wounded, but Donald was fortunate enough not to be among them.

On 4th April 1941, Donald once again boarded a ship as the 2/6th Battalion joined other ANZAC and British troops in Greece. The Wehrmacht had made its way through Yugoslavia with little difficulty and was heading toward the Greek border. Here, Allied forces attempted to prevent German units from crossing the border, but outnumbered and outgunned, they could only hold out for so long. Equipped with heavier armour and enjoying complete air superiority, the German army advanced rapidly, pursuing the retreating Allied forces. By the time the 2/6th Battalion reached the outskirts of Piraeus, where it was supposed to board an evacuation ship, the port had already been destroyed by heavy aerial bombardment. The unit was instructed to move to the Peloponnese for an alternative evacuation point.

The Corinth Canal was a strategic chokepoint on the way to the evacuation points. The ANZAC plan was to withdraw forces south of the canal and evacuate them from ports in the Peloponnese. The 2/6th Battalion was tasked with defending the Corinth Canal to slow down the German advance and buy time for the evacuation. Unfortunately, the German paratrooper assault on Corinth on April 26th disrupted these plans and led to heavy casualties among Australian and other Allied troops. The 2/6th Battalion lost 28 soldiers, with 43 wounded. Although most of the battalion managed to evacuate, 217 members were captured by the Germans, including Private Donald Christie.

Donald was recorded as missing in action by his unit on 2nd June 1941. A month later, he was confirmed as a prisoner of war (POW). He was interned in Stalag XVIII-A, a German POW camp located south of the town of Wolfsberg in the Austrian state of Carinthia. Here Donald had to endure harsh conditions, living in unhygienic conditions of the overcrowded barracks. Winters were especially harsh, since heating was inadequate and there was a scarcity of blankets and proper clothing. Food rations were minimal, consisting mainly of watery soups, black bread, and ersatz coffee.

Prisoners performed forced labour, which ranged from mining to factory production and farming. We might assume that Donald would have been employed in farming, given his previous experience. Many prisoners assigned to work details operated outside the main camp, under its administrative control. It was among these POWs, rather than those in the camp itself, that most escape attempts occurred. We do know that Donald was assigned to two temporary work camps which were engaged in road building.

If Donald was part of any escape attempts, they were unsuccessful. Some Australian POWs from his camp did manage to escape, including Private Walter Gossner of the 2/15th Australian Infantry Battalion. The camp was liberated by Soviet troops in February 1945, however, the Germans had already taken most prisoners on a forced march before this. By May 1945, all prisoners were freed, including Donald Christie. His unit reports that he was recovered to British soil on 21st May 1945. By the time he returned to his home in Australia, in September 1945, he was 27 years old and had spent 1,974 days in uniform. For his service, Donald was awarded the 1939/45 Star, the Africa Star, the Defence Medal, the War Medal 1939/45, and the Australian Service Medal 1939/45. In addition, he was commemorated at the Ballarat Australian Ex-Prisoners of War Memorial.

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 41

The History Guild Weekly History Quiz.See how your history knowledge stacks up. If you would like an invite to future history quizzes please enter your details below. Subscribe * indicates required Email Address * First Name Last Name History Guild Weekly History Quiz Weekly New History Articles and News Monthly History Guild Update

General History Quiz 142

1. L’Anse aux Meadows is an important archaeological site from which culture?

Try the full 10 question quiz.