Reading time: 5 minutes

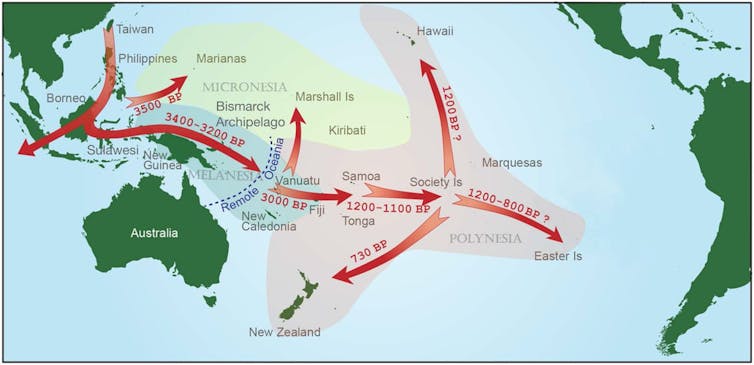

The study of Indigenous languages spoken in maritime South-East Asia today has shed new light on the beginnings of the Austronesian expansion. This was the last major migration of people spreading out across the Pacific Ocean and, ultimately, settling Aotearoa.

Scientists all agree that people speaking Austronesian languages started out from Taiwan and settled the Philippines around 4,000 years ago. They used sails as early as 2,000 years ago. Together with other maritime technologies, this allowed them to disperse to the islands of the Indo-Pacific ocean.

By Victoria Chen, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

There they assimilated with existing populations and eventually reached as far as Easter Island to the east, Madagascar to the west, Hawaii to the north and New Zealand to the south.

But linguists had found little evidence about where precisely the migration started and which Indigenous group was involved in the expansion.

Our new research provides this missing linguistic evidence, based on an overlooked grammatical affix. It suggests the Amis of eastern Taiwan are the closest relative of the Malayo-Polynesian people (including Māori) in the Austronesian language family.

This finding complements recent research in archaeology and genetics, which also suggests the Austronesian expansion likely began along the east coast of Taiwan. Contemporary Indigenous groups in this part of Taiwan are known to have long-standing seafaring traditions.

The Austronesian language tree

Austronesian is the second-largest language family in the world. Austronesian languages are spoken from Madagascar to Polynesia, including te reo Māori, and have been the focus of considerable research. But many basic questions remain about the origin and primary dispersal of this language group.

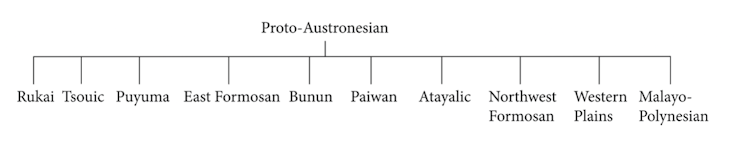

The consensus over the past 50 years had been that Malayo-Polynesian is an Austronesian primary branch with no identifiable closer relationship with any language in the homeland:

However, archaeological evidence indicates a 1,000-year pause prior to the migration. This suggests Malayo-Polynesian should have split off from a certain Indigenous group in Taiwan, rather than starting up as an independent branch.

In our research, we discovered new evidence relating to Malayo-Polynesian’s root. It comes from a special use of the grammatical affix ma in four Indigenous Austronesian languages. Spreading along the east coast of Taiwan, all four languages (Amis, Kavalan, Basay-Trobiawan, Siraya) show a special use of ma that allows the actor of an action to be included in the sentence, for example:

Amis: Ma-curah ni Kulas ku lumaq. Kulas burned the house.

This sentence structure is strictly banned in all other Indigenous languages of Taiwan, but is widely observed in Malayo-Polynesian languages.

Tagalog: Ma-sunog ni Kulas ang bahay. Kulas will burn the house.

Strong seafaring traditions

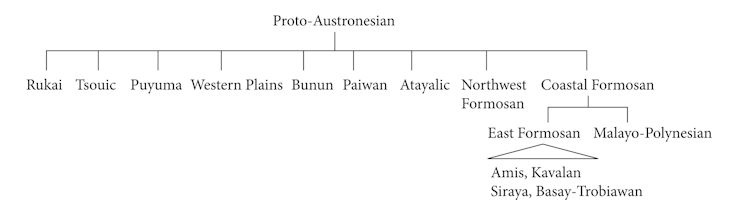

Intriguingly, all four languages have known seafaring traditions, and all belong to the East Formosan primary branch of Austronesian. Their shared use of ma with Malayo-Polynesian thus suggests a new subgrouping in which these two groups share a common origin.

This hypothesis suggests the East Formosan people – including the Amis, the largest Indigenous group of Taiwan – are most closely related to Malayo-Polynesian, including Māori, in the Austronesian homeland.

It also traces the starting point of Austronesian expansion to eastern Taiwan, where three of these four languages are still spoken today.

Our findings point to a revised linguistic subgrouping more consistent with the socio-historical view that a seafaring community began the out-of-Taiwan expansion.

It coincides with recent findings in archaeology, which put the starting point of the Austronesian expansion in eastern Taiwan. It also aligns with three recent genetic studies. All three reveal a particularly close connection between the Amis and Malayo-Polynesian populations.

Exclusively shared vocabulary between Amis and Malayo-Polynesian languages lends further support to this idea. The Amis word poki for vagina, for example, is etymologically unrelated to equivalent words found in other Austronesian languages of Taiwan. Instead, it has the same linguistic derivation as the corresponding words in various Malayo-Polynesian languages.

Papora (Taiwan) huci, Thao (Taiwan) kuti, Bunun (Taiwan) kuti, Paiwan (Taiwan) kutji, Puyuma (Taiwan) kuti.

Amis (Taiwan) poki, Tagalog (Philippines) púki, Malay (Malaysia) puki, Javanese (Indonesia) puki, Tetun (Timor) huʔi-n, Gitua (Papua New Guinea) pugi.

Future investigation of more shared traits between Malayo-Polynesian and East Formosan languages will shed further light on their relationships.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about Austronesian Expansion:

Articles you may also like:

The Two Countries That ‘Escaped’ The Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa is often recognized as the beginning of colonialism and European Imperialism. Beginning in 1884, the scramble brought most of the African continent under European control, barring two countries – Liberia and Ethiopia. However, debate continues over whether these regions truly escaped colonialism as they grapple with the same colonial legacies that […]

Frank Cotton and the Invention of the Australian G-Suit

Reading time: 9 minutes

The best-known wartime innovations are the largest, loudest, and flashiest, from humble handguns to the tank. But war has also prompted the invention of fascinating, and less destructive, devices designed not to harm life, but to protect it. One of these was the anti-gravity suit, or g-suit.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.