Reading time: 1 minute

On May 8, 1945, a battered, broken Nazi Germany surrendered to the Allied armies which had crashed across its borders, fighting town by town to topple Hitler’s regime. Two days later, one of Germany’s strangest supporters surrendered, too.

By Morgan WR Dunn

His name was Martin Monti, and he wore the uniform of a Waffen-SS Untersturmführer, he claimed, only to escape from the Russian forces invading from the east. Long after the Nazi state had crumbled, Monti was still trying to hide the bizarre truth: he was the only American officer to carry the dubious honor of having volunteered for German service.

Politics, Religion, and Isolationism

Martin James Monti was born on October 24, 1921 in St. Louis, Missouri to Martin Monti Jr., of Italian-speaking Swiss descent, and Marie Antoinette Wiethaupt, a German-American. Raised as a Catholic, the young Monti was exposed to an ominous trend in 1930s American politics: isolationism.

One of the most significant figures in Monti’s childhood was Father Charles Coughlin. Every week, 16 million Americans tuned into the “Golden Hour of the Shrine of the Little Flower” to hear Father Coughlin deliver antisemitic lectures and extol the supposed virtues of Nazi Germany.

Young Martin Monti tuned in, too. What’s more, Monti’s father seems to have had a hand in his son’s political development, even taking him to meetings of the isolationist America First Committee. By the time the United States entered World War II on the Allied side, Monti was convinced that the country had been misled into joining the wrong side.

Lieutenant Monti’s Flight

In December 1942, Monti joined the United States Army Air Forces in St. Louis as a trainee pilot. But not long before, in October of that year, he’d made a pilgrimage to Detroit to meet his hero. The subject of the conversation he had with Father Coughlin is lost to history, but if what happened next is any indication, it was during this meeting that Monti began to plot a unique contribution to the war.

After training in Arizona and Florida, 2nd Lieutenant Monti was ordered to Karachi, then in British India, in August 1944 to join the 126th Replacement Depot. But he didn’t stay there long: just six weeks later, without orders, he hitched a ride aboard a C-46 transport plane to Abadan, Iran, then Cairo, Tripoli, and finally to Naples. From there, he went north to Foggia, where he attempted to join the 82nd Fighter Group.

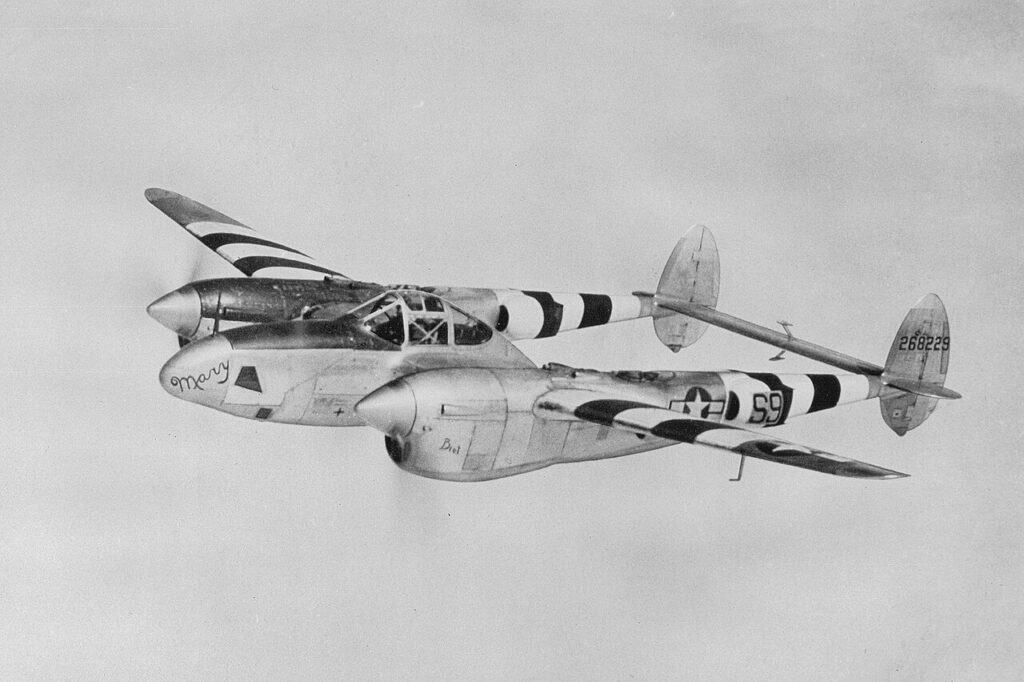

The commander of the 82nd refused Monti’s request, but on his way back to Naples, he stopped off at Pomigliano Airfield, “itching to get his hands on a plane again.” He was in luck: some mechanics at the base pointed out a brand-new Lockheed F-5E, a photographic reconnaissance variant of the P-38 Lightning, which needed a test flight. Claiming to be an 82nd pilot, Monti hopped into the cockpit without orders on October 13th, 1944, and flew north to Milan, where he surrendered himself to the occupying Germans.

In Service to Germany

Monti had developed a reputation for oddness among his fellow trainee pilots. One reported that Monti had once told him that he planned to fly over Switzerland and deliberately bail out, and was known to be opposed to American involvement in the war. Even so, this officer said, “I do not believe he would sell out to the Germans, but he was so queer and strange that he might well do this.”

“Queer and strange” appears to have been his captors’ assessment, too. He wanted, he told his interrogators, “to fight the Bolsheviks, not the Germans,” volunteering to fly against Soviet forces. At first, Monti was held in a prisoner of war camp until he managed to convince the Germans of his sincerity. By then, however, it was far too late for the Luftwaffe to field new pilots. Even Monti’s stolen plane would be pressed into service with the Zirkus Rosarius, a unit tasked with testing Allied aircraft.

But if the young turncoat couldn’t fly, the Nazis could think of one way he could contribute: they asked if he would record propaganda for broadcasting on the German radio network. His answer, it later emerged, was “Yes, if it will get me to Berlin to see Hitler.” He would later deny saying this in court.

In November, Monti was released from the POW camp and sent north to Berlin. There, under the patronage of Louisiana-born Waffen-SS officer Peter Delaney, Monti made his first broadcasts under the name “Martin Wiethaupt,” with the SS-Standarte Kurt Eggers, a propaganda unit.

For four months, Monti lived in Berlin, wearing civilian clothes and carrying a pistol provided by his handlers. He was no Father Coughlin, though – inexperience and a refusal to “undertake anything detrimental to the interests of the USA,” combined with the rapidly deteriorating German situation, gave him little to offer his captors.

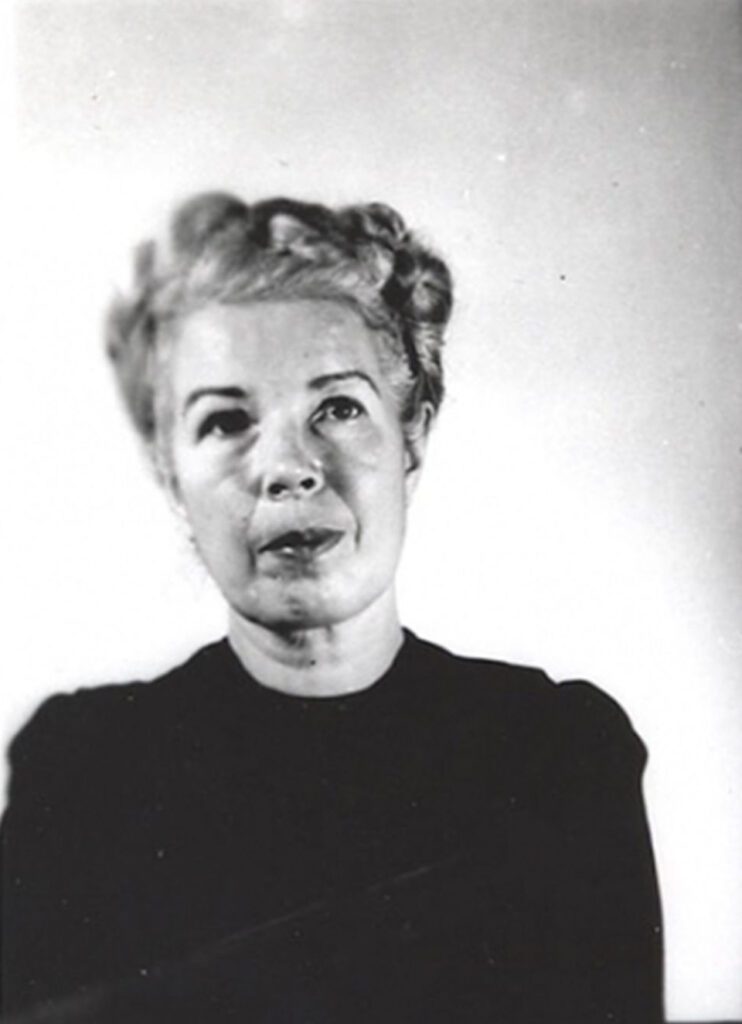

He was also unpopular among German propagandists; the American-born Nazi propagandist Edward Vieth Sittler doubted his reliability, and Mildred Gillars, better known as “Axis Sally,” refused to be in the same room with him, saying “That man is a traitor. I’ll have no part of him.”

By April 1945, it was clear that Germany had no way out. Every German who could carry a weapon was pressed into service, and that month, he and Sittler were ordered to head back to the Italian front – back to Milan – with SS-Standarte Kurt Eggers for the final battle.

“Rejoining” the Americans

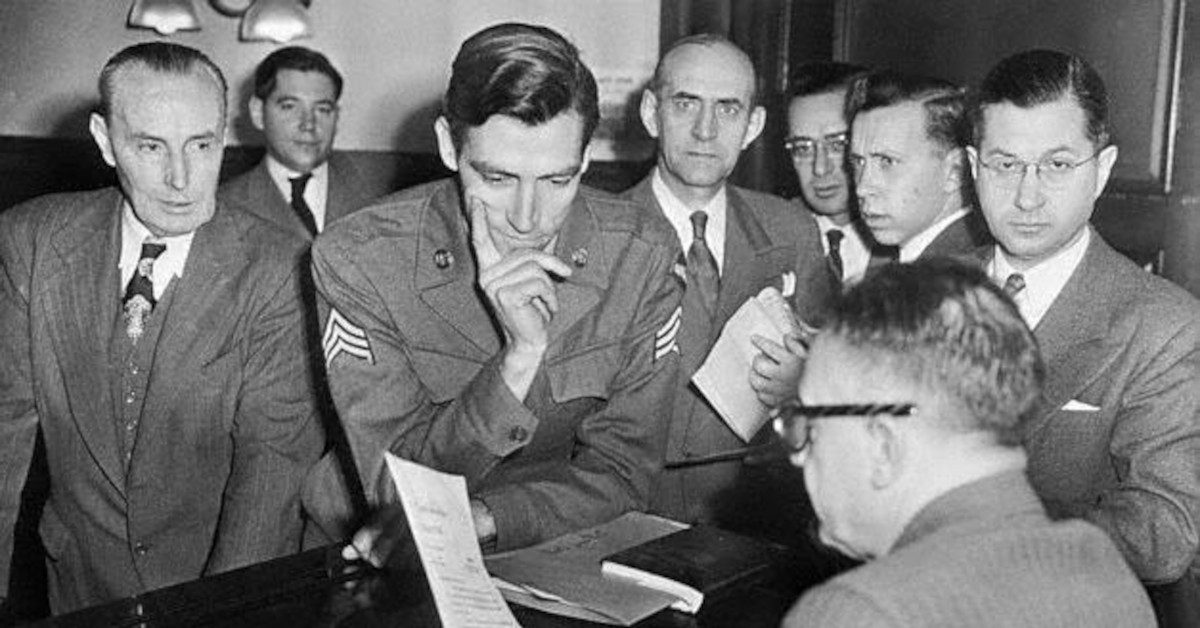

Upon arrival in Italy, Monti proved Sittler and Gillars to be correct: he “joined up,” rather than surrendered to, troops of the United States Fifth Army at the first opportunity. On May 13th, he was interrogated by U.S. intelligence officers, as was standard for captured pilots who’d made their way back to Allied lines.

Monti claimed that Italian partisans had given him the uniform – from which he’d stripped the insignia and other identifying marks – to help him escape. He said nothing about his association with the Waffen-SS or the stolen plane, but it didn’t take long for the Army to find out about it. When confronted at the Red Cross Officers’ Club in Bari, Italy, he admitted to stealing the F5E. In a subsequent court-martial, charged with desertion and theft, he was sentenced to 15 years imprisonment and fined $10,000.

Fortunately for him, he’d covered his tracks. In December 1944, Monti had sent his parents a letter claiming that he was a POW held at Stalag III-D. Based on this, and his father’s request for help, Missouri Representative Walter C. Ploeser intervened with the White House and convinced President Harry S. Truman to commute the sentence to time served if Monti agreed to rejoin the Air Force as an enlisted airman, which he did in early 1946.

Treachery Discovered

In the immediate aftermath of the war, Germany was in such chaos that Monti might have thought his betrayal would never be discovered. But in November 1947, Drew Pearson, a Washington Post columnist known for publicizing General George Patton’s slapping of two soldiers in 1943, described in his “Washington Merry-Go-Round” column what he called “a sort of Rudolf Hess in reverse.”

Pearson’s column brought to the attention of the wider public the truth behind Monti’s wartime escapades, as well as the fact that he was still serving at Mitchel Air Force Base, having reached the rank of sergeant. Having been court-martialed once before, the Air Force couldn’t try Monti again – but the FBI could.

On January 26th, 1948, Monti was discharged from the Air Force and within minutes had been taken into custody, still in uniform. Before his trial began on January 17th, 1949, the possibility of pleading insanity was discussed, investigated, and dismissed; other than some abnormal behaviour, Monti was adjudged to be sane, intelligent, and competent, at the time of trial, when he stole a plane, and when he agreed to work for German radio. Likely under pressure from his defense attorney and his family, Monti pleaded guilty to 21 counts of treason in open court, answering in the affirmative to all the questions put to him by the judge and the prosecutor.

His defense rested on the exemplary service of all four of his brothers in the United States Navy, his youth, and the argument that he was “so blinded” by “what he conceived to be the menace of civilization, namely Communism” that he saw Germany as an ally in defense “of Christian civilization and of his Government.” For his part, Monti claimed that he’d had no choice but to do as his German superiors told him, and that he’d adopted his mother’s maiden name to ensure he could be traced in the event that he was killed.

The prosecutor, Victor Woerheide, summed up his case simply, telling the judge that Monti “did everything that he could to commit treason. He left no stone unturned.” Judge Robert Inch agreed, and sentenced Monti to 25 years at the federal military prison at Fort Leavenworth and a fine of $10,000.

Martin Monti would appeal the sentence twice, in 1951 on the grounds of double jeopardy, and again in 1958 on the argument that the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York which sentenced him had no jurisdiction. Both arguments had been dismissed during his 1949 trial, and his appeals were likewise denied. He was released on July 1, 1960, remaining on parole until 1974.

Martin James Monti, the first American to admit to treason in court and the only U.S. officer known to defect to Nazi Germany, spent the rest of his life in obscurity. He died in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, on September 11, 2000.

He appears never to have spoken again of his brief career in the Waffen-SS and propaganda efforts. But Monti did make one last attempt to clear his name, when he applied to reverse the treason charge with a Brooklyn federal court in 1963. He claimed that “his only reason for going to Germany was to assassinate Hitler and end the war,” and that “he wanted to prevent a Communist takeover in Europe.” This too was denied.

Podcasts about Lieutenant Martin Monti

Articles you may also like

Discoveries Among the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon – Audiobook

DISCOVERIES AMONG THE RUINS OF NINEVEH AND BABYLON – AUDIOBOOK By Austen Layard (1817 – 1894) Austen Henry Layard is best known as the excavator of Nimrud and of Nineveh, where he uncovered a large proportion of the Assyrian palace reliefs known, and in 1851 the library of Ashurbanipal. The Royal Library of Ashurbanipal, named after […]

General History Quiz 112

1. Which civilisation lived along the Tigris and Euphrates river valleys?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.