Reading time: 6 minutes

The middle ages are often associated with lawlessness and brutality. Along with knights in shining armour, the images we often associate with the period are torture devices like the rack, or public punishment like the stocks. Was that really how law and order were maintained in the Middle Ages?

By Fergus O’Sullivan

As with many things in history, the reality is a lot more nuanced than popular perception makes it seem. To get a better idea of how law and order worked, we’ll take a look at law enforcement in medieval England, the country that has had the most literature published in this regard.

How dangerous was medieval England?

Medieval life was in many ways a lot more violent than today. Standards of living weren’t great, people were desperate and often inebriated thanks to many people preferring beer over water as it was considered more nutritious. Fights kicked off quickly, and, due to the prevalence of weapons, those involved often got injured or killed.

Since English life in those times was community-based, criminal matters were usually handled within the community, called a tithing. A tithing (which translated means “ten-thing”) was the people who lived on an area of ten hides, or about 120 acres. However, if a member of a community did something criminal outside of that circle, a whole community could be held liable.

As a result, if the hue and cry was raised after a crime was committed, the whole tithing would spring into action to help catch the perpetrator or run the risk of being held responsible for the crime.

Constables and sheriffs

Tithings were represented by the chief pledge, usually the richest man in the community. However, this person, as a member of the tithing group would always make sure to put his own community first. As a way to increase control, in 1252 Henry III appointed constables (from Latin comes stabuli or “count of the stable”) for criminal matters to each tithing.

The community system wasn’t that easily eradicated, however, and over the years the chief pledge and constable melded into a single function. It became an position that made sure beggars were run off and life ran smoothly. Think of it more as a form of social control than actual policing.

Criminal matters were instead handled by the sheriff (“shire reeve”). Appointed by the king, the sheriff kept an eye on things in an area of one hundred hides, which, after the Statute of Winchester of 1285 was the new administrative unit. Originally a tax collector, the sheriff soon became responsible for locking up miscreants besides also being the leader of the posse comitatus, the local levy, which could both be called on in times of war or could also be used as a local guard.

As an agent of the king, the position of sheriff was highly desirable for any ambitious noblemen. However, they were often seen as people that put the needs of London over that of the local community — Robin Hood’s nemesis is a sheriff for a reason. The fact that they started as tax collectors probably didn’t help.

City matters

In cities and towns, meanwhile, policing was done by the city watch, men paid to do the job. Calling them professional would be an overstatement, though: the watch worked mainly at night and detained everybody they saw — not much reason to be out after dark in an age without lighting. As such, it wasn’t a very prestigious gig and the members weren’t disciplined. There are plenty of stories about watchmen sleeping, drinking, or even extorting people on the job.

How the law worked

If you were caught committing a crime, a few things could happen. If it was something small, you could be shamed by having to spend some time in the stocks as a way to teach you a lesson, or face some other kind of public punishment that acted as a deterrent. More serious infractions, though, were handled more seriously.

Before the Norman conquest, criminal matters were settled through some kind of compensation as everybody still had to get along after everything was said and done. A good example is wergeld or weregild, which in Anglo-Saxon literally means “man-money.” This was the sum paid if a man died or was injured by the family of the perpetrator.

After the conquest, this changed. The Normans instituted trial by combat, which involved the two parties in a legal dispute fighting until first blood or first injury. The loser would then be found guilty and punished, as it was seen as god making them lose.

The second, and more common form of law, was the trial by ordeal. In this case, a priest used cold water or hot iron to test your innocence. Cold water meant throwing somebody into water and if they floated they were guilty as the water didn’t accept them. Hot iron involved somebody holding an iron rod heated over flame and walking a few steps. If after a few days the wounds healed cleanly, you were innocent

As in both cases accused would be in discomfort or pain even if they were innocent, trials weren’t decided on lightly. A jury drawn from the community would decide if it was necessary. In fact, after the trial by ordeal was ended by the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215, this jury instead took over the entire judicial process, under guidance of a Justice of the Peace, another royally appointed function.

Punishment

If found guilty, a number of possible punishments awaited. On paper, most crimes carried the death penalty, especially people convicted of crimes like treason could expect a slow, horrible death. In reality, though, there were a lot of escape valves. Intent mattered a lot and if you could convince a jury you were temporarily rendered mad or under some kind of duress, you may get a lighter sentence. Adding to this was a strong belief in the redemptive potential of humans, inspired by faith.

A common replacement punishment, then and now, was imprisonment. Prisoners were likely held in whatever fortified building there was, like a keep or the city gates. Prisoners were expected to pay their own way, which made for a class system, even in prison. For example, the price to remain free from shackles, called the sewet, could vary wildly depending on location and the prisoner’s station.

Though not the dungeon of popular history, these places can’t have been much fun, either. Alternatively, the convicted could try and run away, with the self-imposed exile acting as a punishment, though starting a new life in the tight-knit communities of the middle ages can’t have been fun, either.

At the same time, though, it’s clear there was more to crime and punishment during medieval times than just torture. There was a strong belief in the redemptive potential of humans, which seems to have guided the process. Though life was tough, there was more to it than just the stock and the rack.

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 210

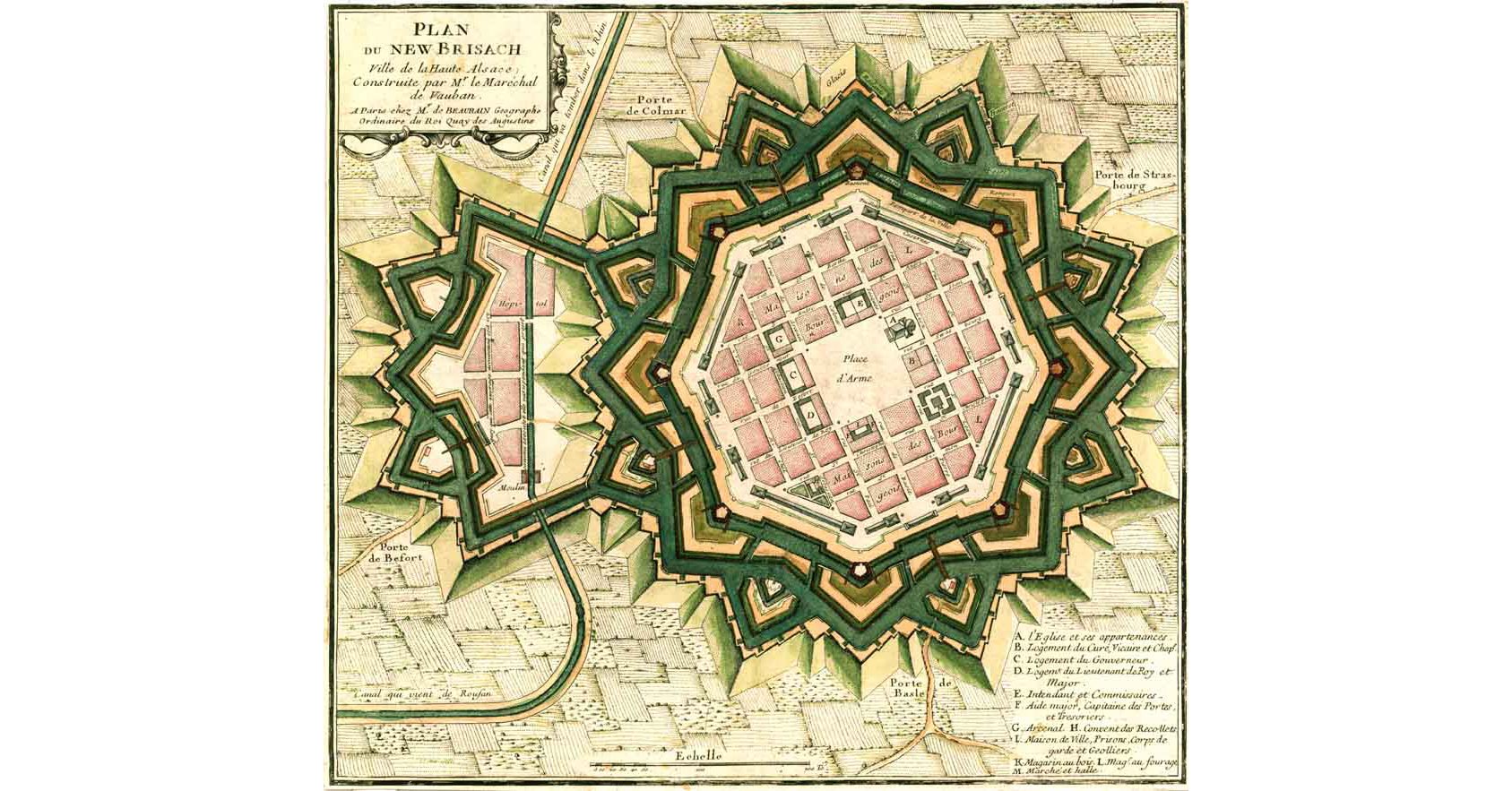

1. Who was Europe’s most prolific military engineer, creating over 150 fortresses?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

Defences of Australia – 19th Century

Modern Australia is relatively unique in it’s position occupying an entire continent, having no land borders with another country. While this provides assurance against a purely land based attack, the 60,000 km coastline offers many opportunities for seaborne invasion. In the 19th century there was a significant fear of invasion by Britain’s enemies, with over […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.