Reading time: 11 minutes

On 12 October 1865, John Davidson, a magistrate in the east of Jamaica, wrote to the island’s Governor, Edward John Eyre:

‘The people at Morant Bay [on the island’s southeast coast, St. Thomas-in-the-East parish] have risen, burnt down the Court-house, released all the prisoners, murdered several white people.’

Colonial Office Confidential Print, ‘Narrative of the rebellion in Jamaica, October 1865, taken from the official despatches’, 1865. Catalogue ref: CO 884/2/4

Within hours of receiving this news, Eyre had sent hundreds of troops to St Thomas. On 13 October he issued a proclamation of martial law for the island’s county of Surrey, which covered its eastern end. This was the Morant Bay Rebellion, an infamous episode of brutal, colonial violence which would reverberate both in Jamaica and in Britain.

By Chris Day.

Background

The rebellion was the result of years of political, economic and racial tensions in Jamaica. The island was in the grip of an economic decline, but had also faced years of epidemics, floods and droughts. The island’s enslaved population had been emancipated on 1 August 1834 but were initially placed in ‘apprenticeship’ to their former ‘masters’, another form of bonded labour, for a period of four to six years. Apprenticeship was abandoned in 1838, but over the next three decades Black estate workers and peasants bore the brunt the economic crises, receiving few civil or religious freedoms from Jamaica’s white (and to a lesser extent, mixed race) elites, who often actively tried to restrict and criminalise them further.

In early 1865, the Jamaican Legislative Assembly had passed Bills against cane cutting, the surreptitious harvesting of small amounts of sugarcane for personal use, a custom which had been relatively tolerated even under slavery. Since emancipation this, and ‘squatting’ on abandoned estates (often the only way labourers could make ends meet), had been codified as crimes. Now the Assembly proposed punishing cane cutting with whipping, or a return to ‘apprenticeship’ for those under 16. Petitioning the Secretary of State for Colonies, Edward Cardwell MP, to veto the Bills, the Anti-Slavery Society noted that ‘the whip is the symbol of slavery’ and its return, coupled with ‘a revival of involuntary servitude or slavery’, expressed a ‘mischievous and dangerous tendency’ on the Assembly’s part. They feared the Black population would be forced to riot if they were carried.

Jamaica’s Black estate workers and peasants were not passive. They organised and campaigned for more equitable treatment and working conditions. One of the mainsprings of these campaigns were the Native Baptist churches. Non-conformist missionaries had been active in the Caribbean since the 17th century, and were blamed for many slave rebellions by Jamaica’s plantocracy. But after emancipation, European preachers’ influence waned. The Native Baptist churches had been started by Black refugees from the American Revolution. Their Gospel was more radical – they merged African cultural practices with Christian ritual, they spoke more to the political concerns of the island’s Black poor. In St Thomas-in-the-East one Native preacher, Paul Bogle, expounded a radical, political vision to his congregation at his chapel in Stony Gut, near Morant Bay.

The Morant Bay Rebellion

Bogle was in Morant Bay on Saturday 7 October 1865. A crowd had assembled for the Petty Sessions, at which the magistrates found a boy guilty of assault and fined him, tacking on much higher court costs for him to pay. James Geoghegan, a Black spectator, urged him to pay the fine but not the costs. The magistrates ordered Geoghegan arrested but he fled into the throng. Two policemen gave chase but were beaten and mocked by the crowd. In consequence, on Monday 9 October, the magistrates issued warrants for Bogle’s and others’ arrests for assisting Geoghegan.

Six policemen and two constables came to Stony Gut on Tuesday 10 October to arrest Bogle, but they were mobbed by more than 300 men armed with cutlasses and sticks, detained for several hours, and made to swear oath that they would ‘join their colour’ and ‘cleave to the black’, drinking gunpowder-laced rum to seal this. Bogle stated that he would go to Morant Bay the next day to see his accusers. The local magistrates called up the militia and requested Eyre send them troops.

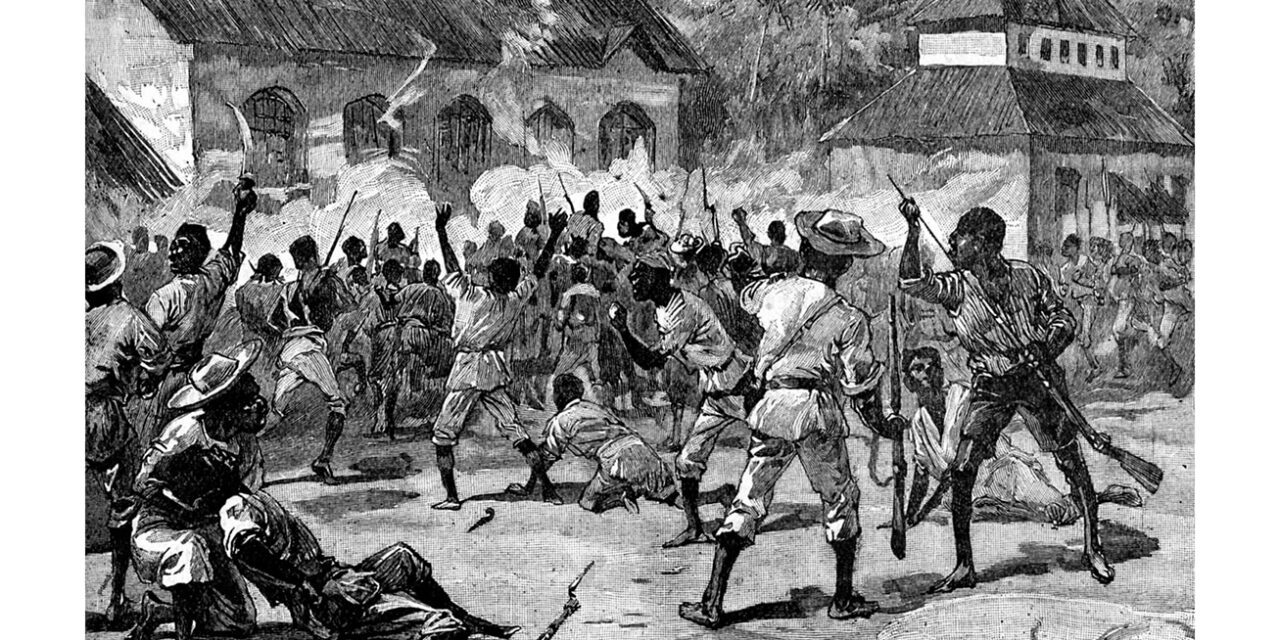

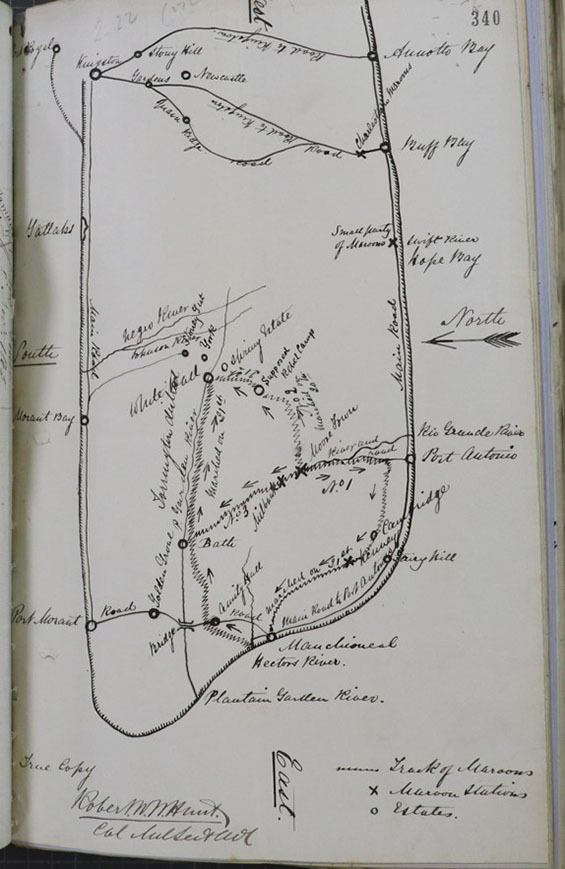

On 11 October Bogle and a crowd of hundreds, some armed with cutlasses and a few firearms, marched to the courthouse. Confronted with the militia, they threw stones and insults. The militia responded by opening fire, and all hell broke loose – the crowd attacked them and set fire to the courthouse. Eighteen militia were killed, while at least seven rioters lost their lives, as the rest began seizing control of the parish. This would last perhaps two days, as troops and Maroons (the descendants of escaped enslaved people who had long lived separately and been employed in supressing rebellion) rushed into St Thomas-in-the-East, unrestrained by Eyre’s martial law proclamation. By the time the rebellion was ‘suppressed’ in early November, 469 Black Jamaicans were dead, executed at hasty courts-martial or otherwise killed. Six hundred were brutally flogged, while a thousand houses were burned.

Bogle evaded capture initially, but was taken by a party of Maroons under Colonel Fyfe on 23 October. They had been tipped off to his whereabouts by a spy, and they ‘came on him unawares when he was coming out of the bush with a sugarcane in his hands’. He was sentenced to death by court-martial and hanged the next day.

Causes and consequences

In his despatches back to London (which were later published in the London Gazette), Eyre related the circumstances of the rebellion, and what he believed had caused it.

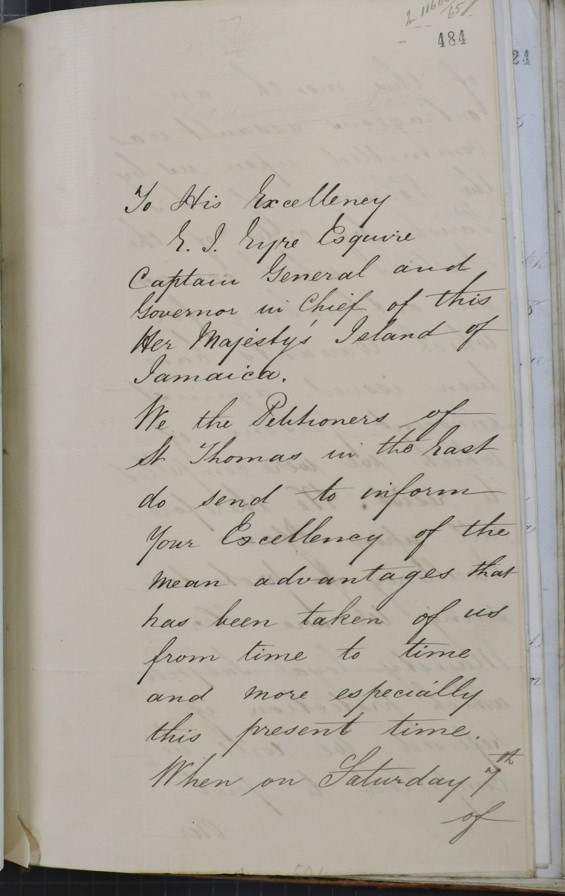

He forwarded a copy of a petition sent to him by Bogle and other rebel leaders on 10 October, the day before the violence at the courthouse. They spoke of ‘the mean advantages that [have] been taken of us’. They asked Eyre of the rights of law they believed they were due, promising that otherwise ‘we will be compelled to put our shoulders to the wheels as we have been imposed upon … for 27 years’, since 1838, when apprenticeship came to an end.

Bogle and his comrades’ rhetoric was even stronger in a letter which Eyre said had been found in a house in Stony Gut during the rebellion. ‘Skin for skin, the iron bars is now broken in this parish’, the letter said. ‘Every black man must turn up at one, for the oppression is too great, the white people are now cleaning up they guns for us, which we must prepare to meet too.’

The despatches also began to give readers in Britain an impression of the brutality Eyre had unleashed in retaliation. His 13 October proclamation of martial law promised ‘that our military forces shall have all power of exercising the rights of belligerents against such of the inhabitants … opposed to our Government’, effectively declaring any rebels to be equivalent to enemy combatants in a war.

A 19 October letter from Colonel J Francis Hobbs, involved in the rebellion’s suppression, to his commanding officer spoke of how, having received rebel prisoners, ‘I had them all shot … then hung them up from trees’. This was not just a restoration of public order, it was a war of terror.

The killing of George William Gordon

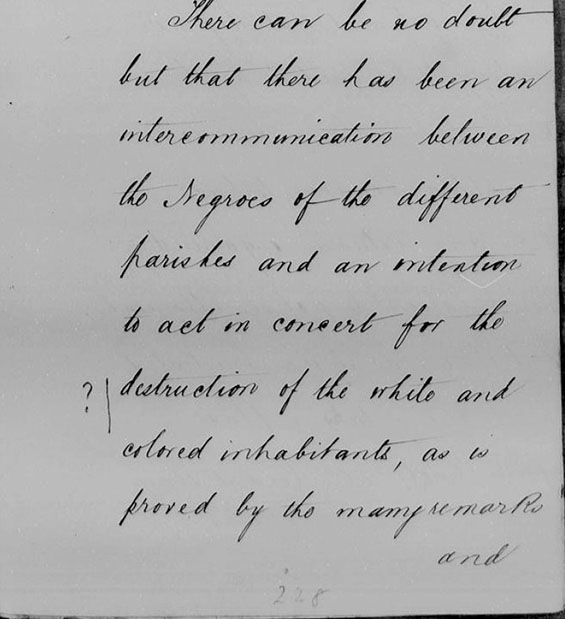

As the Anti-Slavery Society reminded Cardwell in November, Bogle and his comrades’ violence had been precipitated by the militia, who fired the first shots. But Eyre and much of Jamaica’s elite saw a conspiracy for a premeditated revolution on the part of Jamaica’s Black population, ‘an intention … to act in concert for the destruction of the white and coloured inhabitants’. Eyre persisted in this belief despite admitting in the same letter that it did not seem there had ‘been any actually organised combination to act simultaneously’. The Colonial Office in London marked this contradictory reasoning with a ‘?’ in the page’s margin.

Racism, and a desire to utilise the crisis to implicate the elite’s domestic enemies, probably played a part in this reasoning. Eyre, like many white people at the time, believed Black people to be lazy and unintelligent, therefore their political and collective action had to come from an external source – ‘persons of better position and education … engaged in misleading the negro population by inflammatory speeches or writings, telling them that they were wronged and oppressed and inciting them to seek redress’. Eyre saw Baptist preachers, long the bogeyman of Jamaican planters, ‘exciting the ignorant people’ as one source of the unrest; but the ‘chief cause and origin of the whole rebellion’ was apparently one George William Gordon, a mixed-race member of the Jamaican House of Assembly.

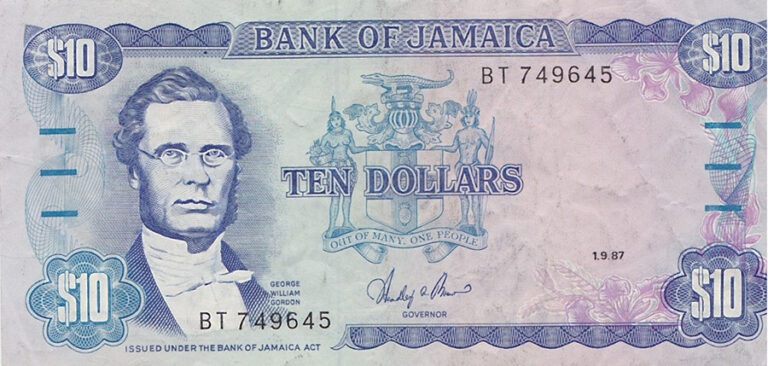

Gordon had been born in 1815, the child of an enslaved woman and her enslaver. He had himself been enslaved until age 10, but was freed and became a successful businessman and then Assembly member for St Thomas. Champion of the parish’s Black poor, a Native Baptist, and friend of Bogle, Eyre and the island’s elite detested Gordon. The Jamaica Tribune newspaper accused him of ‘inflaming’ labourers in September 1865, wondering how he might be ‘punished’. When Morant Bay erupted, Eyre gained an opportunity.

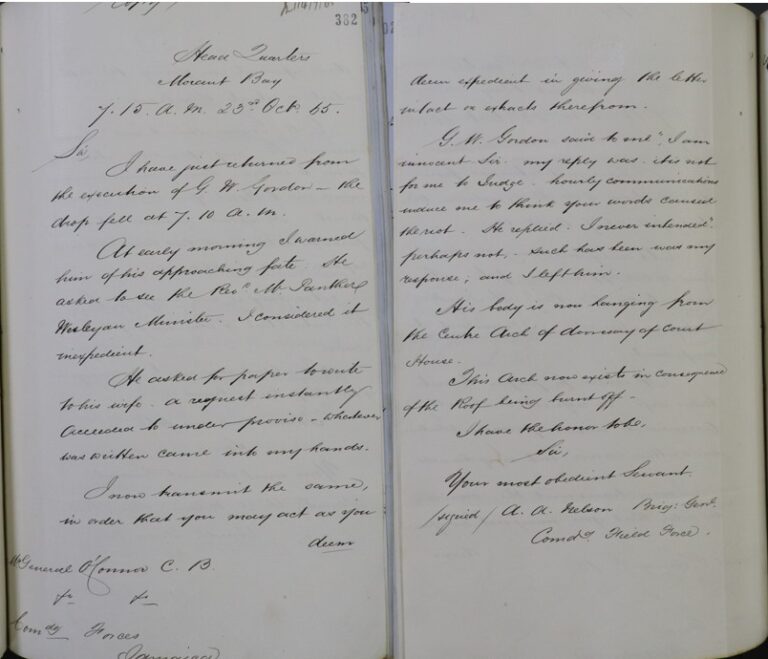

Gordon’s treatment at Eyre’s hands during the rebellion was extraordinary. Gordon was in Kingston, which Eyre had exempted from martial law. Yet the Governor had him arrested and his papers seized, then put him on a Royal Navy ship bound for Morant Bay. At a court-martial, he was rapidly convicted of treason as the leader of the rebellion, on flimsy evidence. He was hanged in the ruins of Morant Bay’s courthouse on Monday 23 October at 07:00, and left hanging in its burnt central arch as a warning. The legality of his arrest with almost no evidence was dubious enough, but Eyre’s rendition of someone arrested on a civil charge to a court-martial was as extraordinary as it was illegal.

Aftermath

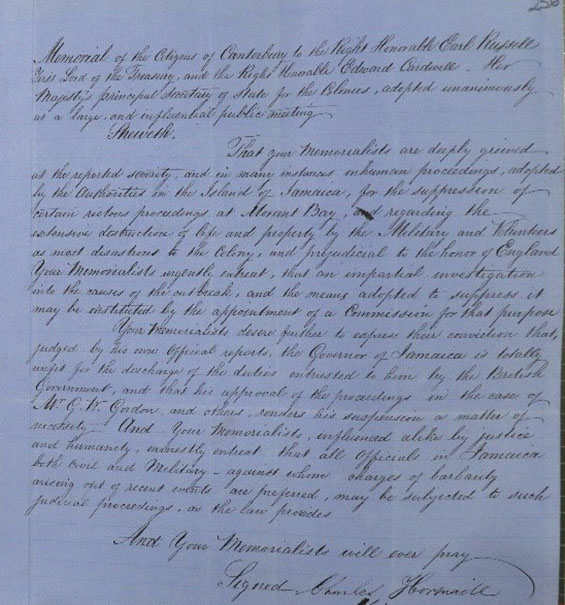

Initially much of Britain was sympathetic to Eyre – the memory of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and other colonial uprisings had convinced many of the need for ‘natives’ to be ruled hard. But as details emerged of the shocking brutality, the tide began to turn. The Anti-Slavery Society condemned the ‘indiscriminate massacre of coloured people’. They were not the only ones: a ‘large and influential public meeting’ in Canterbury petitioned the Prime Minister, John Russell, regarding the ‘inhuman’ repression, ‘disastrous to the colony and prejudicial to the honour of England’. They demanded that Eyre be removed from office. Theirs was one of many such petitions.

Eyre was eventually suspended but not before the Jamaican Assembly passed an Act of Indemnity protecting him and others from legal cases regarding their various unlawful actions in the rebellion. The Act needed approval from the British Privy Council; the Anti-Slavery Society begged Cardwell to refuse it. He and the government prevaricated as to the Bill’s, and Eyre’s, fate.

A Royal Commission was created by Parliament to enquire into the rebellion’s suppression. It reported in April 1866, adopting an equivocal tone – acknowledging the high death toll, cruelty and barbarity of the reprisals, but saying Eyre had been right to take decisive action, whatever its legality. Eyre had supporters in Britain too. The historian Thomas Carlyle and novelist Charles Dickens were among those who believed his actions justified the need to dominate Black colonial populations.

The new Tory Government of 1866 decided not to punish Eyre. He was in court over the rebellion, the government covering his costs and pensioning him off. He died in Devon in 1901. Eyre’s memory lives in infamy – ‘the unscrupulous tool of the West-Indian planter’, as Karl Marx described him. Gordon and Bogle, meanwhile, are two of the seven National Heroes of Jamaica, their faces on coins and banknotes, their lives and legacies celebrated.

This article was originally published by the National Archives.

Articles you may also like

Women in the Second World War: Military service in East Africa

Reading time: 8 minutes

Hundreds of women served with the British Army in East Africa, and their role in the conflict goes largely untold.

Annexation or Liberation? India, Portgual, and Goa: 1961

Reading time: 10 minutes

On 18th July 1947, British rule in India came to an end, closing a 300-year old chapter in the history of the subcontinent. But another empire had been in India for over a century more, and it would be over a decade later that this longer story was finished.

D-Day succeeded thanks to an ingenious design called the Mulberry Harbours

Reading time: 4 minutes

When Allied troops stormed the beaches at Normandy, France on June 6, 1944 – a bold invasion of Nazi-held territory that helped tip the balance of World War II – they were using a remarkable and entirely untested technology: artificial ports.

To stage what was then the largest seaborne assault in history, the American, British and Canadian armies needed to get at least 150,000 soldiers, military personnel and all their equipment ashore on day one of the invasion.

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.