Reading time: 11 minutes

Modern special forces are capable of astonishing feats of arms, from crippling their opponents’ infrastructure to derailing entire campaigns. While soldiers have been detailed for highly specialised and dangerous tasks since before history began, the first true forbears to today’s special forces were first established in the midst of the Second World War, when the Axis powers seemed poised to seize victory at any moment.

By Morgan WR Dunn

Australia’s contribution to the field, Operation Jaywick, was the brainchild of an unshakeable British officer and a grizzled Victorian sailor. Fleeing the chaos of the British Empire’s defeat at the hands of Japan, Ivan Lyon and Bill Reynolds brought an audacious idea to Z Special Unit, Australia’s wartime special forces command.

With a tiny handpicked crew and an inconspicuous vessel, they would carry the fight back to the Japanese and set the stage for a series of military escapades which left a legacy lasting to this day.

An Escape and an Idea

When Bill Reynolds, a 61-year-old sailor and adventurer, first set eyes on the boat that would put him in the history books, it was still the Kofuku Maru, a 68-ton, 70-foot Japanese motor sampan built in 1934. Reynolds spotted the vessel in Singapore Harbour in 1942 as the Imperial Japanese Army ripped into Britain’s city-state outpost, and he had orders to remove or destroy anything that could be of use to the enemy on his way out of town.

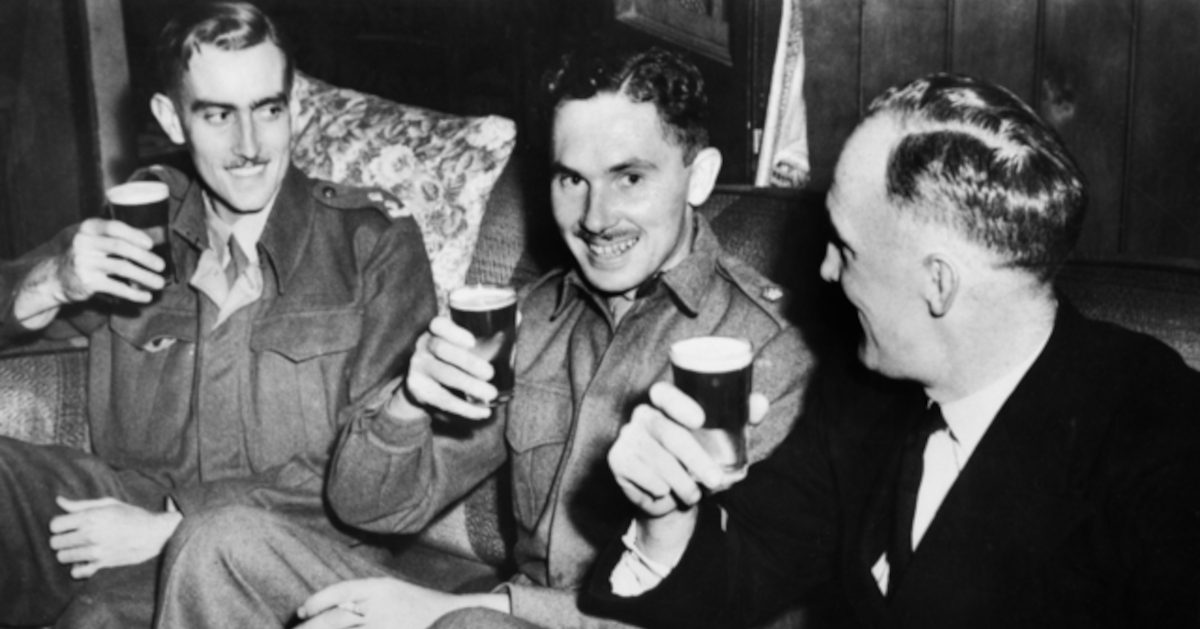

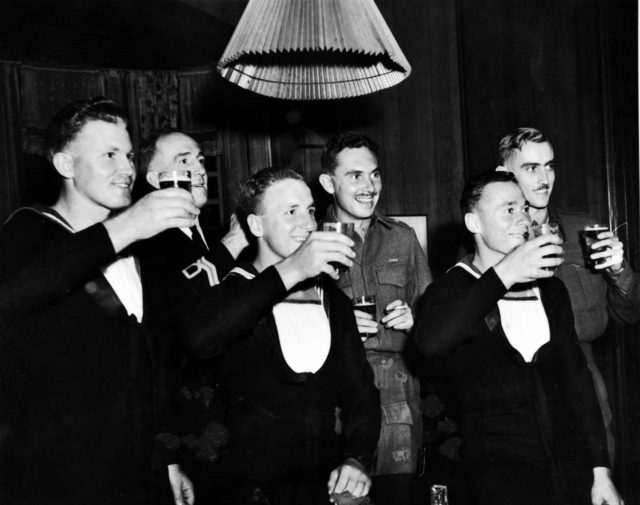

As he piloted the craft away from the disastrous surrender, he nearly collided with another vessel carrying Captain Ivan Lyon, an officer of the British Army’s Gordon Highlanders, and his Welsh batman, Corporal Ron “Taffy” Morris. Later, over conciliatory beers on Sumatra after making good their escape, Lyon and Reynolds hatched a scheme which any sane soldier wouldn’t have come close to: the innocuous little boat, they reasoned, had made it past the Japanese once; there was no reason to think it couldn’t do the same thing going back into Singapore, only this time it could carry a small group of highly-trained explosives experts to wreak havoc among Japan’s merchant fleet.

The escapees carried the idea to General Archibald Wavell, who immediately supported the plan. Lyon and Reynolds received orders to report to a sub-unit of the Special Operations Executive, Britain’s wartime asymmetrical warfare agency. The fishing trawler Reynolds had snatched from Singapore would be their vehicle. To mark its new purpose, Lyon renamed it MV Krait, after the small but lethally venomous Indian snake. After many months of preparation, the little craft and its crew would make good on the name.

Assembling the Crew

Lyon was given a free hand to select the best recruits and veterans for his operation. His second-in-command was Lieutenant Donald Davidson, Royal Naval Reserve, “a tall, fearsome-looking fellow whose steely eyes seemed to bore right through whoever happened to be speaking to him” who was fond of thinking of novel methods of killing and maiming.

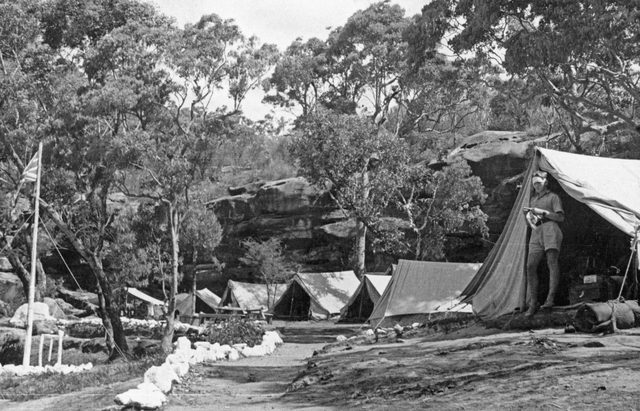

The two officers spent weeks scouring Australian training establishments searching for the right kind of men for the job. The physical demands were intense, but Lyon was looking for mental as well as physical strength in his recruits, and for agreeability. More than one potential Z Force man was weeded out as Lyon took note of who complained, demonstrated laziness, or simply irritated him. By 11th September 1942, the number had been whittled down to 11.

The final crew roster was made up of sailors Kevin Cain, Mostyn Berryman, Arthur Jones, Frederick Marsh, Andrew Huston, and Walter Falls; Corporals Taffy Morris and Andrew Crilly; radio operator Horrie Young; navigator and pilot Lieutenant Ted Carse; engineer Paddy McDowell; and officers Lyon, Davidson, and Bob Page.

This group Davidson subjected to a grueling training regimen focusing on “canoeing, fitness, hand-to-hand combat, night navigation, and weapons and explosives.” They also trained with folboats, the ingenious collapsible canvas canoes which would deliver six of them to their targets in Singapore Harbour.

Finally, on 8th August 1943, the Krait, with crew complete and holds and decks packed with knives, grenades, firearms, survival and navigation supplies, medicine, food, water, trading goods and money, and 70 kilograms of plastic 808 explosive, “enough to sink about 15 ships”, strapped to the radio shed, pulled away from Australian waters and set a course for points north.

The Lion’s Den

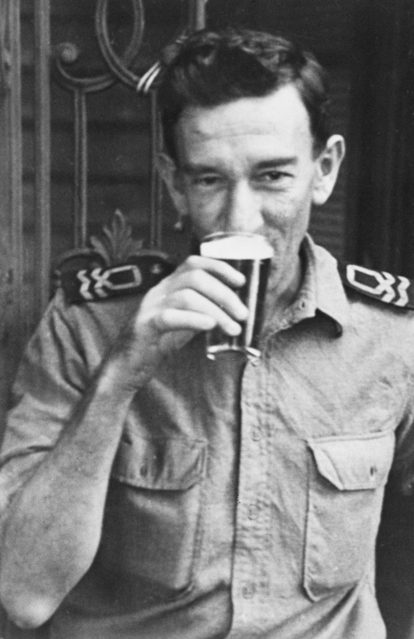

The SOE and Australian naval intelligence had gone to great lengths to ensure the Krait and her cargo reached their destination undetected. The cosmetics firm Helena Rubinstein had even been contracted to provide a skin dye to help the crew look Asian from afar, causing Carse to comment that “a more desperate looking crowd I have never seen.” Lyon did the rest, imposing bans on smoking, throwing garbage over the side, and the use of toilet paper. As they sailed north through the Lombok Strait and west through the Java Sea, he was taking no chances of failing so close to his target.

At last, on 18th September, the Krait dropped off six men, three folboats, supplies, and explosives and weighed anchor. Horrie Young, who remained aboard, later said that “I think most of us had doubts as to whether we would ever see our colleagues again.” The Krait would cruise around the area, staying out of sight as best they could. The assault team prepared for the most daring Allied operation the Pacific had yet seen.

The folboat crews kept watch until the night of 26th September 1943. Under cover of darkness, the team paddled 50 kilometres and slipped through the dark waters at the entrance of Singapore Harbour.

The Serpent Strikes

The first canoe, crewed by Lyon and Huston made for Examination Anchorage; the second, carrying Davidson and Falls for the eastern end Keppel Harbour; and the third, with Page and Jones, headed for the western end. The boats arrived just after 21:00.

The trip was uneventful, apart from Davidson and Falls nearly getting run down by a tug and Lyon and Huston being spotted by a man through a porthole. Luckily, they were ignored. Paddling under the port sides of the largest merchant ships they could find, they attached limpet mines to the hulls. About four hours after they’d infiltrated the Harbour, the folboat crews slipped back out, undetected, and made for their hiding spot to the south.

Just before daylight on 27th September, the timed mines went off in a series of seven explosions. Each explosion accounted for a ship, together totaling more than 26,000 tons of shipping – more than any single Royal Australian Navy vessel sank throughout the war. “The sirens and noise,” read the official report on the operation, “continued most of the morning of the 27th September,” while small vessels raced to contain the damage and Japanese forces launched a furious search for the attackers.

But the attackers, who’d watched the destruction from afar, had already taken off for Pompong Island, their rendezvous with the Krait. By the night of 3rd October, all three folboat crews had been collected. Carse recorded “Picked up remainder of personnel and returned down Strait. Well we are on our way home. Thank God!”

The Legend of the Krait

A key objective of Operation Jaywick was propaganda value, to show demoralised Allied personnel that the Japanese were not invincible, but the operation was kept secret. Still, it had been a resounding success, and among the first attacks of its kind, setting the stage for many more raids to come.

Moreover, it hadn’t been a complete secret: the Naval Board report on Operation Jaywick noted that some Malays “appeared to take great delight in imitating the noise of the explosions, while raising both hands upwards and outward presumably in imitation of the effect of the explosions.” And while the crew of the Krait returned with no losses and to great acclaim, the same couldn’t be said for local Singaporeans. Because the Allies didn’t acknowledge their involvement, Japanese occupiers assumed Jaywick was the work of local resistance groups and launched a round of reprisals, killing and torturing civilians.

Many of the Jaywick operatives would meet tragic and violent ends as the war drew on. Bill Reynolds was assigned to intelligence work, captured, and taken to Java in 1944. He was shot in August. Ivan Lyon would go on to many more special operations. His last would be Operation Rimau, a larger imitation of Jaywick carried out in October 1944 along with five other Jaywick veterans.

After inflicting limited damage on Japanese shipping, Lyon and a few other men fled to the small island of Soreh to the south of Singapore. In the evening of 16th October, he and two others held off a Japanese search party for hours, killing many from the treetops with silenced Sten guns and hand grenades. The sole survivor of the group, Corporal Clair Stewart, was captured and eventually beheaded on 7th July 1945 – less than a month before the Japanese surrender. Davidson, Page, Falls, Huston, and Marsh were also presumed killed during Rimau.

The Krait was turned over to the maritime arm of the SOE for further clandestine use. It was later repurposed for coast guard duties until it was acquired by the Australian War Memorial in 1985. From 1988, it was quietly displayed in Sydney, less popular with visitors than the World War II destroyer HMAS Vampire or the replica of HMS Endeavour. In 2015, however, growing recognition of the importance of the vessel and its crew’s achievement led to plans to restore the Krait, both to preserve it and to present it as it would have appeared over 70 years before.

The surviving crew were dispersed back to their units. All were decorated, but the operation wouldn’t be made public until 1946, when the Australian government acknowledged the “outstanding bravery and devotion to duty under circumstances of extreme hazard” shown by the crew of the Krait. Some of the Jaywick veterans would later help with the recording of the event and with the restoration of their boat. All of them were exceptionally proud of what they’d accomplished. As former Able Seaman Berryman later noted, “Nobody in the history of the world had ever gone that far into enemy territory and come out alive.”

Podcast episodes about Operation Jaywick

Articles you may also like

War Flying by a Pilot – Audiobook

Written in training and in active duty during World War 1, published in 1917. This volume was assembled to provide useful information for young men who might like to become pilots for the Royal Flying Corps. A mixture of conversational letters, poems, and descriptions of flying.

The absurd irony of Putin’s invocation of Stalingrad

Reading time: 5 minutes

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s address in Volgograd on 2 February, in which he sought to draw moral parallels between the heroic Soviet defence of Stalingrad in World War II and the current Russian invasion of Ukraine, represents a new low for Kremlin propaganda.

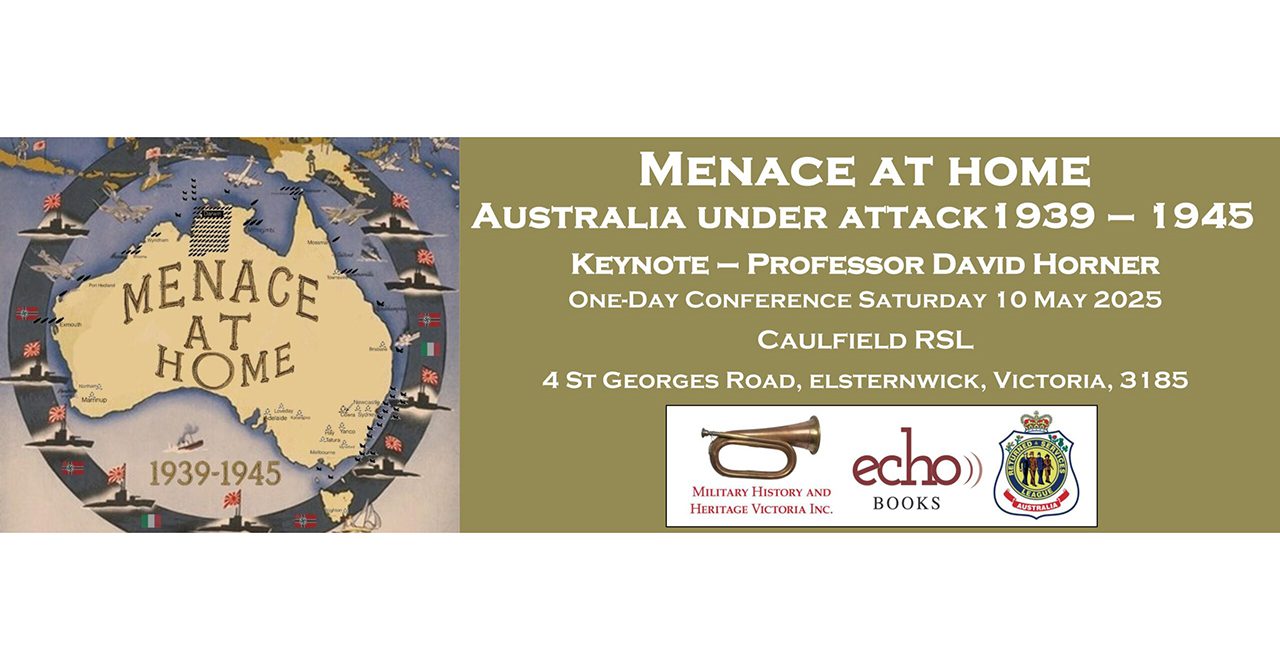

Menace at Home – Australia Under Attack 1939-1945 Conference – Melbourne 10th May

10th May 2025, from 9:00 am to 5:00 pm. This one-day conference will explore the numerous ways Australia was attacked during the Second World War. Between 1939 and 1945, over 1,800 enemy air raids targeted northern Australia, while the nation’s coastal waters were patrolled by raiders, sea mines, and submarines. People of various backgrounds—friends, foes, […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.