Reading time: 6 minutes

Fashion is political — today as in the past. As Britain’s Empire dramatically expanded, people of all ranks lived with clothing and everyday objects in startlingly different ways than generations before.

The years between 1660 and 1820 saw the expansion of the British empire and commercial capitalism. The social politics of Britain’s cotton trade mirrored profound global transformations bound up with technological and industrial revolutions, social modernization, colonialism and slavery.

By Beverly Lemire, University of Alberta

As history educators and researchers Abdul Mohamud and Robin Whitburn note, the British “monarchy started the large-scale involvement of the English in the slave trade” after 1660.

Vast profits poured in from areas of plantation slavery, particularly from the Caribbean. The mass enslavement of Africans was at the heart of this brutal system, with laws and policing enforcing Black subjugation in the face of repeated resistance from enslaved people.

Western fashion reflected the racialized politics that infused this period. Indian cottons and European linens were now traded in ever-rising volumes, feeding the vogue for lighter and potentially whiter textiles, ever more in demand.

My scholarship explores dimensions of whiteness through material histories — how whiteness was fashioned in labour structures, routines, esthetics and everyday practices.

Whiteness on many scales

Enslaved men and women were never given white clothes, unless as part of livery (servants’ uniforms, which were sometimes very luxurious). Wearing white textiles became a marker of status in urban centres, in colonizing nations and in colonies. Textile whiteness was a transient state demanding constant renewal, shaping ecologies of style. The resulting Black/white dichotomy hardened as profits from enslavement soared, with a striking impact on culture.

Whiteness in clothing, decor and fashion was amplified, becoming a marker of status. Elaborate washing techniques were used to achieve material goals.

British sociologist Vron Ware emphasizes “the importance of thinking about whiteness on many different scales,” including “as an interconnected global system, having different inflections and implications depending on where and when it has been produced.” Accordingly, fabrics, laundry and fashion were entangled in imperial aims.

Pristine whiteness in garments

Laundering was codified in household manuals from the late 1660s, a chore overseen by housewives and housekeepers. Women with fewer options sweated over washtubs, engaged in ubiquitous labour with the aim of pristine whiteness.

In colonial and plantation regions, where lightweight fabrics were key, Black enslaved women were tasked with this never-ending drudgery. Only a few profited personally from their fashioning skills.

This workforce was vast. Yet few museums have invited visitors to consider the processes of soaking, bleaching, washing, blueing, starching and ironing required by historic garments.

A recent exhibit at Agnes Etherington Art Centre at Queen’s University curated by Jason Cyrus, a researcher who analyzes fashion and textile history, examined slavery and North American cotton production.‘Black Bodies, White Gold: Unpacking slavery and North American cotton production,’ video from Agnes Etherington Art Centre about Black life at the core of the Victorian cotton industry.

Laundry labour of enslaved women

The skilled labour of enslaved women was a core component of every plantation and an essential colonial urban trade, given the resident population and many thousands of seafarers and sojourners arriving annually in the Caribbean — all wanting clothes refreshed.

Ports throughout the Atlantic were stocked with wash tubs and women labouring over them. Orderly material whiteness was the aim. Mary Prince recorded her thoughts about a demanding mistress in Antigua, who gave the enslaved Prince weekly “two bundles of clothes, as much as a boy could help me lift; but I could give no satisfaction.”

Prince only earned money laundering for ships’ captains during her “owners’” absence. Within port cities, including the Caribbean and imperial centres, this trade allowed some enslaved women mobility and sometimes self-emancipation. But fashioning whiteness was a fraught process, with many historical threads.

Colour scrubbed from recovered statues

From the 1750s, European fashion and artistic style was increasingly inspired by perceptions of the classical past. Countless portraits were painted of wealthy people as Greek gods, the classical past becoming, as cultural theorist Stuart Hall observed, a “myth reservoir.” These became sources for imagining Europe’s origins and destiny.

European scholars and the educated public viewed this cultural lineage as white. Remnants of polychrome colouring was scrubbed from recovered Greek sculptures.‘Vox’ video about the white lie we’ve been told about Roman statues.

This supposed heritage of a white classical past defined what became known as neoclassical styles further expanding the craze for light, white gowns, a political fashion needing endless care.

In this era, “the term classical was not neutral,” as art historian Charmaine Nelson explains, “but a racialized term …” Nelson states that the category “classical” also defined the marginalization of Blackness as its antithesis.

Today, some scholars are wrestling with the legacy of racism built into classical studies.

Racialized masquerade

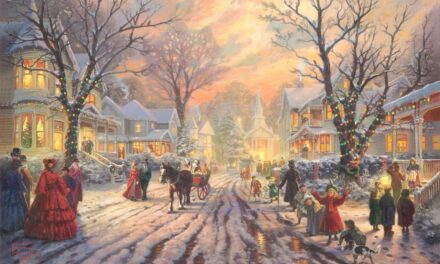

Neoclassical gowns reflected this zeitgeist, as ladies disported themselves as Greek goddesses. Ladies’ magazines urged readers to play-act as deities. Simple socializing en vogue would not suffice. Fashion required a wider stage.

Masquerade balls became the venue where whiteness and empire aligned, as goddesses robed in white mingled with guests in blackface or regalia appropriated from colonized peoples.

Masquerades became staple occasions, revels led by royals, nobles and those enriched through trade and slave labour.

Race hierarchies enforced

Seemingly banal routines (and stylish affairs) reveal cultural facets of empire where race hierarchies were reinforced. In this era, everyday dress and celebratory fashions demanded relentless attention.

These routines were enmeshed with empire and race, whether in the colonial Caribbean or a London grand masquerade.

The proliferation of white linens and cottons were purposefully employed to enforce hierarchies. The rise of white clothing and neoclassical style can be better understood by addressing mass enslavement as an economic, political and cultural force shaping styles, determining vogues and promoting the fashions of whiteness.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about historic whiteness in fashion and arts:

Articles you may also like:

A Voyage Towards the South Pole and Round the World – Audiobook

On his first journey Cook mapped the east coast of Australia, on his second the British Admiralty sent him into the vast Southern Ocean. Equipped with one of the first accurate chronometers, Cook pushed his small vessel not merely into the Roaring Forties or the Furious Fifties but become the first explorer to penetrate the Antarctic Circle, reaching an incredible Latitude 71 degrees South, just failing to discover Antarctica.

A new narrative unfolds about South Africa’s protracted war in Angola

Reading time: 5 minutes

The book A Far-Away War: Angola 1975 – 1989, about the war waged by apartheid South Africa against its neighbour, has attracted the attention of historians and those who fought in it. More than a quarter of a century after it ended, the war is still remembered by many who were touched by it in one way or other.

Women in the Second World War: Military service in East Africa

Reading time: 8 minutes

Hundreds of women served with the British Army in East Africa, and their role in the conflict goes largely untold.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.