Reading time: 5 minutes

King Arthur is one of, if not the, most legendary icons of medieval Britain. His popularity has lasted centuries, mostly thanks to the numerous incarnations of his story that pop up time and time again.

By Raluca Radulescu, Bangor University

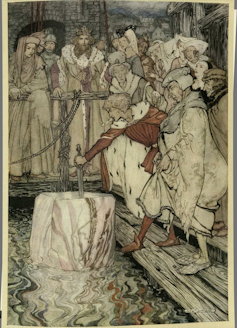

Indeed, his is one of the most enduring stories of all time. Though his tale is rooted in the fifth and sixth centuries, it has continued to captivate audiences to this very day. There is just something about the sword in the stone, the knights of the round table, Lancelot, and the wizard Merlin, that have kept us coming back to the various legends of King Arthur for such a long time.

In the last 15 years alone, there have been Hollywood movies, computer games, and other creative re-tellings. With Bangor University’s new Centre for Arthurian Studies and Guy Ritchie’s movie, King Arthur: the Legend of the Sword, there is no doubt both the scholarly search for Arthur and the impact of his legends on modern culture are continuing to flourish.

Arthur’s life story is one that has become almost a standard for knightly heroes to aspire to. He is seen as brave, noble, kind – everything that some might say is missing from our modern world.

The epic hero

Few might know that Arthur is a hero whose ancestry goes back to the Brittonic inhabitants of early medieval Wales before the arrival of the Saxons, and not just the kingly figure that appears in later romances. In fact, the Arthur of legend was neither a king, nor the owner of a round table, at least not in the way we use these terms today.

Records about Arthur’s life are few and far between. He emerges in the sixth century in the work of the Welsh monk Gildas, where his victory at Mount Badon is celebrated, but he is not named. It is only in the ninth century Historia Brittonum, composed by another monk, Nennius, that Arthur is named as a “dux bellorum”, a military commander, and his 12 battles are listed.

Much time passed between these early records and the 12th century’s full-blown accounts of Arthur’s reign – in the work of Geoffrey of Monmouth and the French Chretien de Troyes, the writers who truly made Arthur the legendary king we now know – and he took on a variety of roles.

In the Welsh stories, Arthur remains a warrior, often a foil for other heroes’ path to greatness. But in the early French romances, he provided a yardstick for courtly behaviour, as epic battles do not form the backbone of these later stories written on the continent. Geoffrey of Monmouth brought back the leadership and determination of an Arthur who becomes not only a king (on whom 12th century Anglo-Norman kings could model themselves), but also a conqueror – again reflecting a desire for greatness beyond national boundaries. Thus the image of the courtly king, a leader in both war and times of peace, was born.

A modern legend

However, Arthur was always connected to the realities of those countries, and the times and peoples for whom he was reinvented. The Arthurian revival of the late 19th century, for example, helped put him back on the international cultural map by removing the historical aura, and emphasising the values he stood for – a far cry from the medieval attempts to utilise him as a national figure from whom medieval kings could derive their right to rule. This paved the way to the fantasy worlds created, most famously, by T.H. White in The Once and Future King, published in 1958.

All of these interpretations were about more than just revealing the secrets of one of the most intriguing men of all time. In this confusing and sometimes frightening world, audiences seek reassurance in the models of the past. They want a standard of moral integrity and visionary leadership that is inspirational and transformational in equal measure. One that they cannot find in the world around them, but will discover in the stories of King Arthur.

Is our modern appetite for fantasy a reflection of our need to reinvent the past, and bring hope into our present? Moral integrity, loyalty to one’s friends and kin, abiding by the law and defending the weak, form the cornerstone of how Arthurian fellowship has been defined through the centuries. They offer the reassurance that doing the morally right thing is valuable, even if it may bring about temporary defeat. In the end, virtues and values prevail and it is these enduring features of the legends that have kept them alive in the hearts and minds of so many through the centuries.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about King Arthur

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 90

1. When did the English monarchy cease to claim that they were also the monarch’s of France?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

Quantity Becomes a Quality All of Its Own

In the history of warfare, there have been mismatched conflicts where skilled forces have been gravely outnumbered By Caitlan Hester What leads to success or failure when quality grapples with quantity? Does victory boil down to ingenuity or is it a sheer numbers game? In this post, we’ll examine three times the underdog was underestimated; […]

David Grann’s The Wager: a drama of murder, insurrection, escape and an empire at sea

Reading time: 7 minutes

In 1740, a modest squadron of ships from Britain’s Royal Navy departed Portsmouth in pursuit of an immoderate treasure. Commodore George Anson, who led the flotilla, was tasked with sailing south and west across the Atlantic Ocean, rounding Cape Horn, and interfering in imperial Spain’s lucrative trans-Pacific trade. But even before the mission got underway, its prospects of success appeared dubious. A sizeable proportion of the roughly 2,000 sailors and non-seamen under Anson’s command lacked suitable experience. Worse still was the fact that so many of them took up their posts already in a parlous state of health. It is little surprise, therefore, that Anson’s “famous” voyage around the world proved to be, for most of the men who undertook it, a journey of no return.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.