Reading time: 6 minutes

Maybe seven really is a magic number. 2017 certainly has a lot of tricks up its sleeve. And as we’ve heard in recent weeks, 2017 is the 50th anniversary of the 1967 referendum, the 25th anniversary of the Mabo ruling, the 20th anniversary of the Bringing Them Home Report and the 10th anniversary of the Northern Territory intervention. These are all significant milestones in Australian history and the legal, political and cultural relationship between Australia’s colonisers and its colonised.

In May, we witnessed the historic coming together of 250 indigenous delegates at Uluru to determine what form of constitutional recognition to seek from the Australian parliament.

Clare Wright, La Trobe University

But this is not the first time that locally elected delegates have gathered in one location to thrash out the legal and moral framework for establishing the principles through which our nation should be constituted and our people counted.

This year is also the 120th anniversary of the Australasian Federal Convention. In April 1897, ten elected delegates from each of Australia’s colonies (except Queensland, which did not attend) gathered at Parliament House in Adelaide to map the route to nationhood, a Commonwealth of Australia.

Six years earlier, delegates appointed by the colonial parliaments met in Sydney to discuss a draft constitution for federating the British colonies in Australia and New Zealand. But 1897 was the first time that members of the Constitutional Convention were appointed by popular vote. (New Zealand was no longer included, having decided that being part of a trans-Tasman Commonwealth was not in its best interests.) Here was a novel experiment in democracy: allow the people to elect representatives to draft a constitution that would be submitted to the people for their assent.

Much has been made of the lack of unity at the Uluru Convention. But surprise, surprise: the 1897 Convention was no chorus of harmonious hallelujahs either.

Democratic sentiment in the last decade of the 19th century — a mood for inclusivity and openness to progressive change — did not necessarily subvert the age-old mechanisms of power; in particular, the fact that those who have it want to keep it. According to historian John Hirst,

the constitutional conventions were horse-trading bazaars at which premiers and their cohorts worked to protect the interests of their colonies.

Commerce and finance also manoeuvred to secure their short and long term investments. Hirst argues that if Federation was a business deal, as is commonly averred, it was a shaky one, with issues such as tariffs more often “divisive and tricky” than designed to broker consensus.

One major point of discrepancy among delegates at the People’s Conventions is what became known as “the Braddon Clause” (named after then Premier of Tasmania, Edward Braddon) whereby three-quarters of customs and excise revenue acquired by the Commonwealth would be returned to the states. Critics of “the Braddon Claws” feared this would lead to smaller states pilfering the profits of the more populous states. While Braddon’s initiative became Section 87 of the Commonwealth Constitution, many other issues were determined provisionally, with the get-out-of-jail-free rider “until the parliament otherwise decides”.

“Votes for Women”

Perhaps the most significant of the Federal Convention’s sticking points was the issue that would eventually make Australia a global exemplar in democratic practice: women’s suffrage. “Votes for Women” was the international catch-cry of the day, but in Australia, on the precipice of nationhood, the matter turned on what could be termed the “constitutional recognition” of women.

At the 1897 Convention in Adelaide, “warm Federalist” Frederick Holder and Charles Kingston, South Australia’s premier, proposed that full voting rights for all white adults should be written into the Constitution. Three years earlier, South Australian women had become the first in the world to win equal political rights with men: the right to vote and to stand for parliament. (New Zealand women won the right to vote in 1893, but eligibility to stand was withheld until 1919.) Playing with a home ground advantage, Holder moved to add a clause to the draft Constitution that read “no elector now possessing the right to vote shall be deprived of that right”.

Other delegates were left speechless. Edmund Barton, who would become Australia’s first prime minister, found words to express the horror:

As I understand the suggestion, it means that if the Federal Parliament chooses to legislate in respect of a uniform suffrage in the Commonwealth, it cannot do so unless it makes it include female suffrage.

If South Australian women could not lose their citizenship status — their right to be counted — then the rest of Australia’s women must achieve it.

Barton spelled out the inescapable conclusion: ‘It ties the hands of the federal parliament entirely.“

Holder and Kingston threatened that, should the new clause not be approved, South Australia would vote against joining the Commonwealth. Despite Barton’s protests, a poll was taken and the ayes won by three votes. Universal suffrage effectively became the precondition of a federated Australia.

However, the Commonwealth Franchise Act of 1902, which made Australian women “the freest of the free”, was the same legislation that stripped Aboriginal Australians of their citizenship rights – legal personhood – which they would not claw back until 1967.

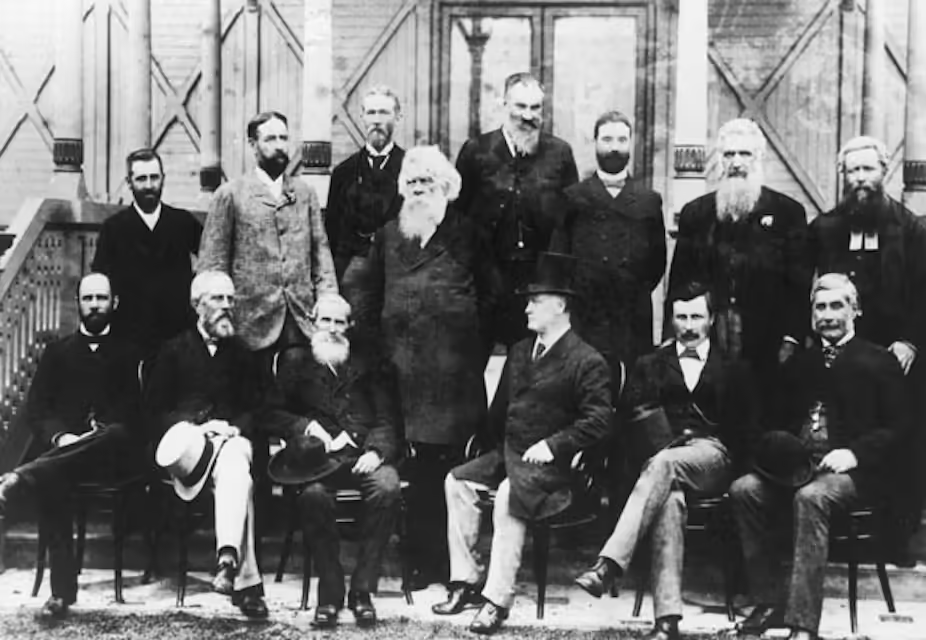

If the founding fathers had one thing in common, it was that they were indeed all men. Monochrome photos of the Constitutional Conventions depict the monocultural make-up of the delegates, whether elected or appointed: white, bearded, suited.

But there were plenty of founding mothers in the wings. South Australian Catherine Helen Spence became Australia’s first female political candidate when she unsuccessfully stood as a candidate for the 1897 Convention. (Another 2017 anniversary, albeit one of apparent failure.) Spence’s proposal for political reform – what she termed “pure democracy” — did make it into the Constitution: the principle of one-man one-vote was not her idea exclusively, but she fought for it with ferocious tenacity.

According to her biographer, Susan Magarey, Spence also made proportional representation “the talk of the colony”, later developing a system for the fairest distribution of preferences (a system so unwieldy it has never been implemented). Though Spence was a leader of the women’s suffrage movement in South Australia, her life’s major mission was to rectify the injustices of the electoral system to ensure “the elevation, educational and spiritual, as well as economic, of all humanity”.

Alfred Deakin concluded that Federation was achieved through a series of miracles. The road to nationhood was not always smooth, seamless or virtuous. Vested interests, entrenched prejudices, competing perspectives and outsized personalities meant that achieving “consensus” was a juggling act that required immense skill and determination. Balls fell. Some were picked up and thrown back in the ring. The nation that emerged was, and is, complex and conflicted.

Catherine Helen Spence’s system for electoral reform may not have been initiated, but let’s hope that the ongoing process of constitutional reform ultimately achieves her broader goal: the elevation of all humanity.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about how women won the vote in Australia

Articles you may also like

Sino-Vietnamese War

Reading time: 5 minutes

The Sino-Vietnamese war was a short, nasty conflict fought between China and Vietnam in early 1979. Largely forgotten by almost everybody including the belligerents, it was a side plot of the Sino-Soviet split, itself a sideshow to the Cold War. Let’s go over the events before, during and after the war to see what it was all about.

Menin Road – Podcast

In 1917, General Haig began what would become known as the Third Battle of Ypres, with the intention of capturing the village of Passchendaele. But getting to the village would require a series of bite-and-hold battles. In September, the 1st and 2nd Australian Divisions, along with British and South African Divisions, launched the third in the series of assaults, at Menin Road. For the first time in history, two Australian divisions would be fighting side-by-side. If they were to ever have this chance again, they would have to prove just how formidable they could be.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.