By Megan Stronach, University of Technology Sydney and Daryl Adair, University of Technology Sydney

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images and names of deceased people.

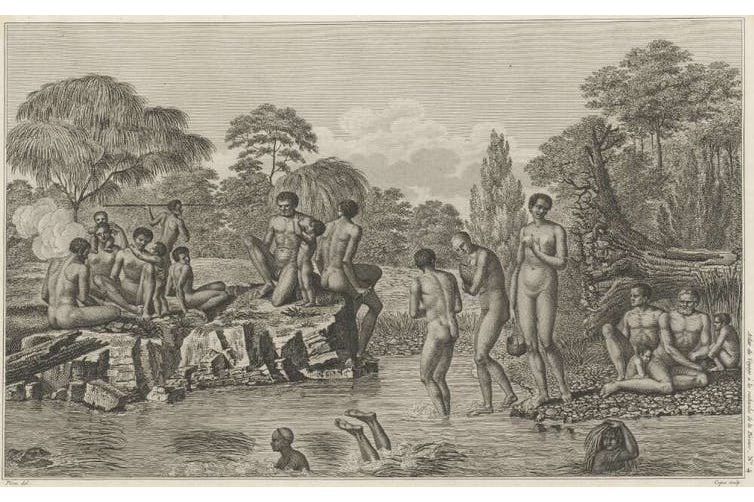

Aboriginal women and girls in lutruwita (Tasmania or Van Diemen’s Land) were superb swimmers and divers.

For eons, the palawa women of lutruwita had productive relationships with the sea and were expert hunters. Scant knowledge remains of these women, yet we can find fleeting glimpses of their aquatic skills.

Wauba Debar of Oyster Bay’s Paredarerme tribe was stolen as a teenager to become, according to Edward Cotton (a Quaker who settled on Tasmania’s East Coast), “a sealer’s slave and paramour”.

Servitude and rescue

Foreign sealers arrived on the Tasmanian coastlines in the late 18th century. The ensuing fur trade nearly destroyed the seal populations of Tasmania in a matter of two decades.

At the same time, life became extremely difficult for the female palawa population.

Slavery was still legal in the British Empire, and so the profitability of the sealing industry was underpinned by the servitude of palawa women.

Sporadic raids known as “gin-raiding” by sealers rendered the coastlines a place of constant danger for female palawa.

National Library of Australia.

Little is known of Wauba Debar other than tales of a daring rescue at sea. Though variations to her story can be found, it most frequently details her long swim and lifesaving efforts in stormy conditions. As one version tells it:

The boat went under; the two men were poor swimmers, and looked set to drown beneath the mountainous grey waves. Wauba could have left them to drown, and swim ashore on her own. But she didn’t.

First, she pulled her husband under her arm — the man who had first captured her — and dragged him back to shore, more than a kilometre away. Wauba next swam back out to the other man, and brought him in as well. The two sealers coughed and spluttered on the Bicheno beach, but they did not die. Wauba had saved them.

Death at sea

Sadly, no one was there to rescue Wauba when she needed it. Her demise during a sealing trip, was at the hands of Europeans.

According to a sailor’s account to Cotton, Wauba was one of the “gins” captured to take along on a whaleboat sailing from Hobart to the Straits Islands (Furneaux Group) as “expert hunters, fishers, and divers, as in most barbarous tribes, the slaves of the men”.

The sailing party camped at Wineglass Bay but woke to find the women and dogs had vanished. A group set off to pursue those who’d taken them. In his 1893 account, Cotton speculated in The Mercury newspaper on the likely cause of her death:

Wauba Debar had, I suppose, been captured in like manner … and possibly died of injuries sustained in the capture, which no doubt was not done very tenderly.

The crew interred Wauba at Bicheno, and marked her grave by a slab of wood with details inscribed.

Accounts differ as to when this actually took place. In 1893, elderly Bicheno residents said Wauba was buried 10 years before the date on the headstone, placing her death around 1822.

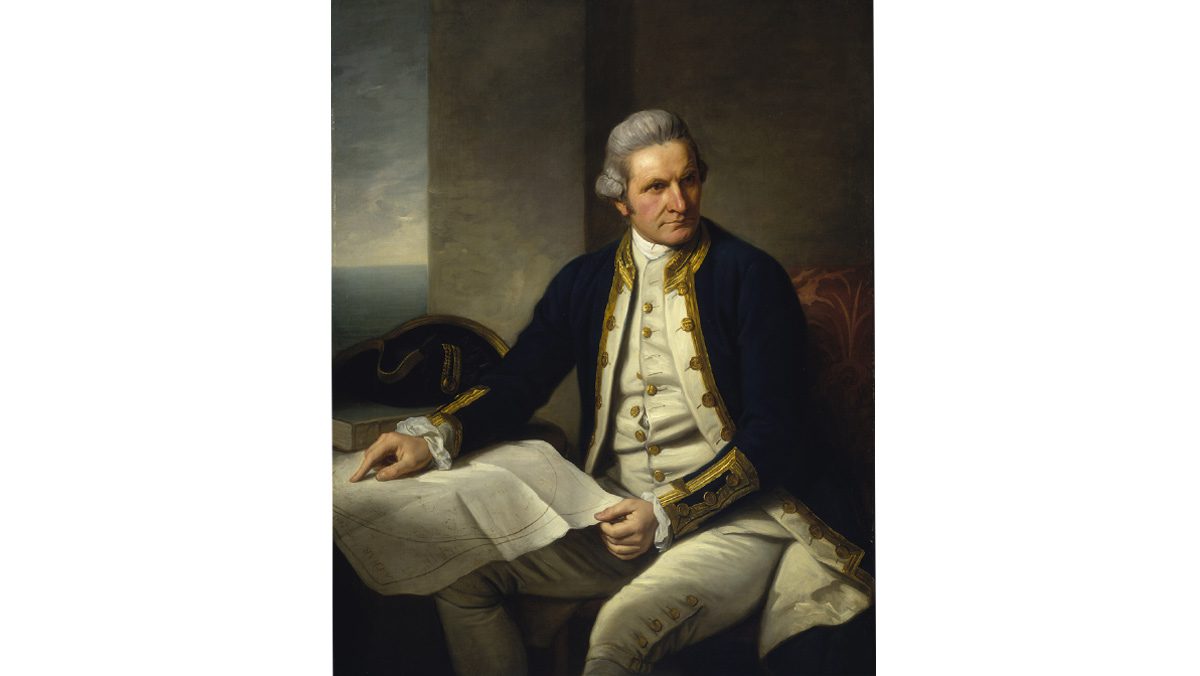

However, in his diary entry on 24 January 1816, Captain James Kelly described how he hauled up in Waub’s Boat Harbour due to the heavy afternoon swell. Considering the area was already named after her, it can be concluded that Wauba was likely buried before 1816.

Cotton’s report imagined her burial:

Wauba Debar did not live to be a mother of the tribe of half-bred sealers of the Straits, which became a sort of city or refuge of for bushrangers in aftertime … But she, poor soul was buried decently, perchance reverently, and I suppose other of the captured sisters would be present by the graveside on the shores of that silent nook near the beached boat.

Here lies Wauba

Wauba’s reputation was such that in 1855 the public of Bicheno decided to commemorate her by erecting a railing, headstone, and footstone (paid for by public subscription) at her grave, with “Waub” carved into it.

John Allen, who had been granted land nearby, donated ten shillings towards the cost of the gravestone – notwithstanding his involvement in a massacre at Milton Farm, Great Swanport, 30 years earlier.

The inscription reads:

Here lies Wauba Debar. A Female Aborigine of Van Diemen’s Land. Died June 1832. Aged 40 Years. This Stone is Erected by a few of her white friends.

Whether prompted by a sense of loss, guilt, or admiration, the community memorialised Wauba, and by extension, the original inhabitants of the land.

Yet by the late 1800s, European demand for Aboriginal physical remains for “scientific investigation” was high. In 1893, the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery was determined to procure the remains of Wauba.

Waub’s Bay, Bicheno, is named after Wauba Debar.

The prevailing ethnological theories believed that the study of Australian Aboriginal people, and particularly Indigenous Tasmanians, would reveal much about the earliest stages of human development and its progress.

Wauba’s grave was exhumed, put into a box, labelled “Native Currants”, and dispatched to Hobart.

The locals were outraged. An editorial in the Tasmanian Mail newspaper condemned the act as “a pure case of body snatching for the purposes of gain, and nothing else” that “the name of Science is outraged at being connected with”.

Snowdrops bloom

Wauba’s memorial is the only known gravestone erected to a Tasmanian Aboriginal person during the 19th century, and she is the only palawa woman known to have been buried and commemorated by non-Indigenous locals.

In 2014, Olympic swimmer and Bicheno resident Shane Gould dedicated a fundraising swim to Wauba Debar’s swimming abilities and memory.

The European styled memorial serves as a reminder of the more turbulent interactions between the two peoples that shaped Tasmania’s history from the 1800s onwards.

Wauba’s empty grave is Tasmania’s smallest State Reserve. Her remains were returned to the Tasmanian Indigenous community in 1985. Snowdrops are said to bloom around the grave every spring.![]()

Megan Stronach, Post Doctoral Research Fellow, University of Technology Sydney and Daryl Adair, Associate Professor of Sport Management, University of Technology Sydney

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

This podcast provides more insight into this area.