Reading time: 6 minutes

The Great Barrier Reef is incredible, with turquoise water, stunning reefs and white sandy cays. Yet its name infers something quite different – a barrier: treacherous, dynamic and dangerous to navigate.

For millennia, people navigated and traded across the northern coast of Australia and the Coral Sea.

When early European seafarers came face-to-face with the world’s largest coral reef system, it was not the beauty they saw, but a nearly unnavigable structure that could easily sink their ships.

Throughout the past 230 years, over 1,200 vessels met their end on the reef – but only 114 have been found.

Each site holds the potential for a wealth of archaeological and historic heritage, as well as tales of disaster, death and lessons learnt about the reef. Preservation, future management and care of these sites is essential.

Our shipwrecks should be visited and enjoyed by the public, yet we should also strive to protect them for the future. We can never replace these sites – once gone they are lost forever. Here are four particularly infamous shipwrecks on the Great Barrier Reef.

By Maddy McAllister, James Cook University

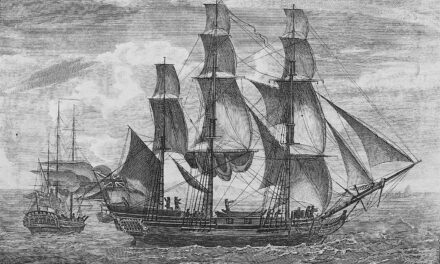

HMS Pandora (1791)

The tale of HMS Pandora is the lesser known – yet perhaps more disastrous – sequel to the infamous maritime tale of the “Mutiny on the Bounty”.

Pandora was the Royal Navy ship sent to hunt down the Bounty mutineers in 1791. After months of searching the south pacific and finding only 14 of the mutineers, Captain Edwards turned for home via passage through the Torres Strait.

The 24-gun frigate ran aground onto the reef, eventually sinking in 30 metres of water. One mutineer and 35 crew lost their lives, and the survivors made a phenomenal journey in long boats to Indonesia (then Java).

The ship was lost to history until divers searching for the site found it buried beneath sand and well-preserved in 1977. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, archaeological excavations provided a wealth of information about life on-board a naval ship in the 18th century.

Artefacts from the wreck include an enormous six-pounder cannon, ceramics, belt buckles, ivory instruments and even delicate organics like rope and cloth.

To date, Pandora is the earliest known shipwreck on the Great Barrier Reef.

SS Gothenburg (1875)

Perhaps one of the most horrific shipwrecks to occur on the Great Barrier Reef is SS Gothenburg.

Built in the UK in 1854, the 60 metre long steam ship operated as a regular passenger service between Australia and New Zealand, and later between Adelaide and Darwin. Gothenburg’s fateful last voyage was a trip from Darwin to Melbourne carrying 37 crew and 98 passengers, including some of Darwin’s elite citizens, as well as 93 kilograms of gold valued at £40,000 (A$1,000,000 today).

Gothenburg encountered cyclonic weather and struck reef southeast of Townsville. The crew attempted to reverse the vessel off the reef, which ultimately damaged the hull further. Worsening weather pushed the steamer further onto the reef, sweeping people into the ocean.

Although one lifeboat made it out, help arrived too late and only 22 people survived. Grisly details arose of bodies seen still clinging to the staircase as salvage divers investigated the wreck to recover the gold.

Gothenburg was found in 1971 by divers sitting in 9 to 16 metres of water and identified in 1978. Maritime archaeologists continue to learn from Gothenburg: the wreck provides insight into life onboard a steam ship in Australia and management of iron steamships in reef environments.

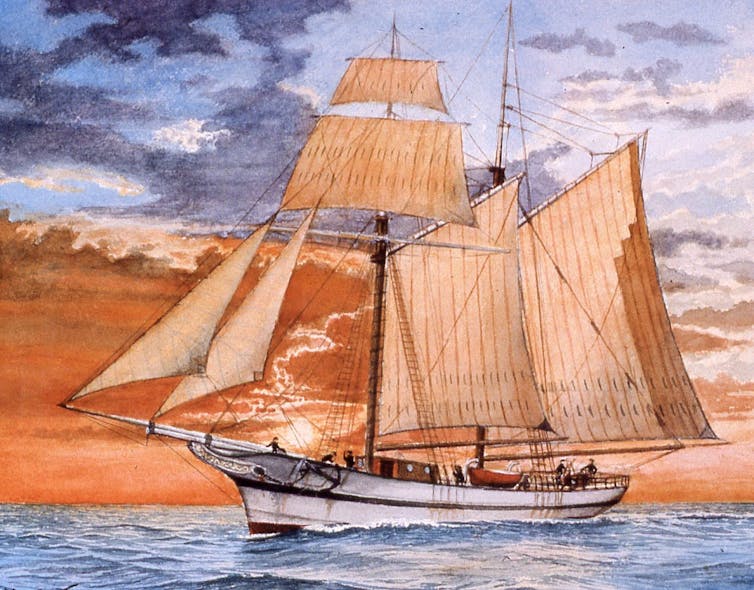

Foam (1893)

In 1893, a wooden topsail schooner ran aground on Myrmidon Reef east of Townsville. The shipwreck remained undiscovered in six metres of water until identified as Foam in 1982.

Foam is the only known wreck on the Great Barrier Reef of a Queensland vessel engaged in the labour trade at the time of its demise. Its discovery helped shed light on the recruitment and transport of indentured labourers from the South Sea Islands, known as blackbirding.

Among the artefacts collected from the wreck were many ceramic armbands used for trade.

Maritime archaeologists now know these armbands were European copies of the shell armbands traditionally used by South Sea Islanders as indicators of status or for trade: the Europeans were introducing counterfeit copies into the Islanders’ exchange systems.

Foam continues to reveal information about the labour trade and influences at the time.

SS Yongala (1911)

SS Yongala disappeared without a trace in March 1911, likely having encountered an unexpected cyclone. Known as “Australia’s Titanic”, all 122 people on board disappeared without a trace. The location of the 100 meter long steamship remained a mystery until discovered lying in 30 meters of water off Alva Beach in the 1950s.

Today, the haunting grave site has become a unique oasis.

Yongala is one of the most intact historic shipwrecks in Australian waters and ongoing research is exploring how it has become the habitat for a remarkably diverse range of marine life (particularly coral). The wreck is ranked as one of the top ten best wreck dives worldwide.

This article was originally published in The Conversation

Articles you may also be interested in

The Scrap Iron Flotilla – Australian Destroyers in the Mediterranean – Video

Anyone looking at the old, small and slow destroyer group would think the same. Soon, however, the Axis and the rest of the world would learn just how formidable it was. The ‘Scrap Iron Flotilla’ and those who manned it proved just how much grit, determination and valour can achieve.

The Battle of Cape Spada: The Australian Navy Proves Its Mettle

Reading time: 9 minutes

The Battle of Cape Spada was a short, violent encounter on the 19th of July, 1940 where the cruiser HMAS Sydney of the Royal Australian Navy sank one Italian cruiser and severely damaged another off the coast of Crete. In this article, we go over the events of that day, as well as what life was like for the crew of the ship.

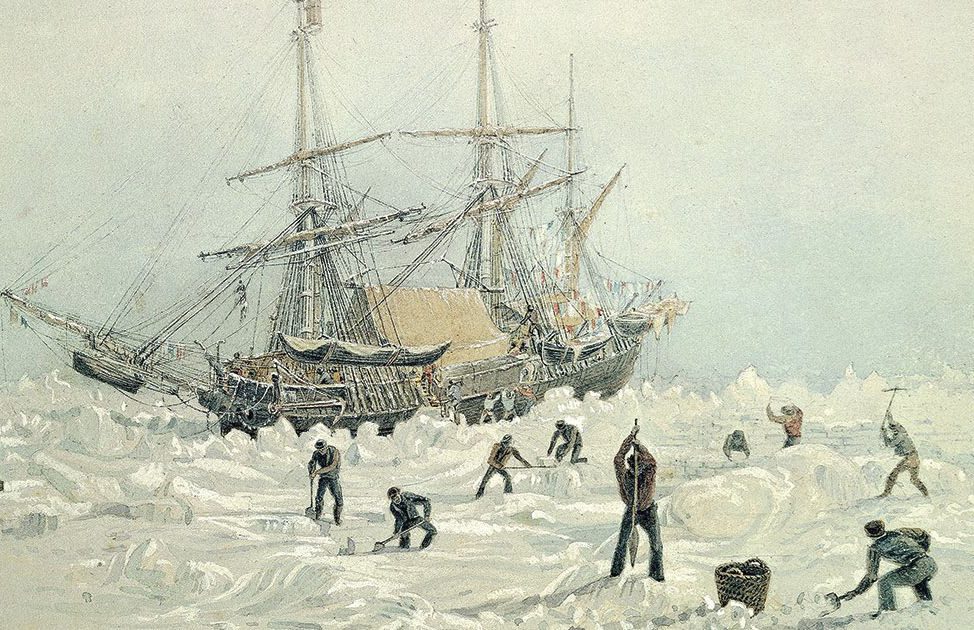

HMS Terror wreck found – but what happened to her doomed crew? Here’s the science

It remains one of history’s best-known naval tragedies – and mysteries. The loss of all 129 men of the 1845 Royal Navy expedition led by Captain Sir John Franklin to navigate a north-west passage through the Arctic remains an enigma. The only informative document to be recovered from the expedition was a single page that reported initial […]

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.