Reading time: 6 minutes

The German-Jewish painter and writer Paul Cohen-Portheim had spent a peaceful summer in 1914 visiting friends in Devon and enjoying the beautiful south-west coast. But his idyllic holiday came to an abrupt end after Britain’s entry into war on August 4. Despite there being no suggestion of any sympathy towards his homeland’s military ambitions, Cohen-Portheim was classified as an “enemy alien” and prevented from leaving the country.

By Stefan Manz, Aston University

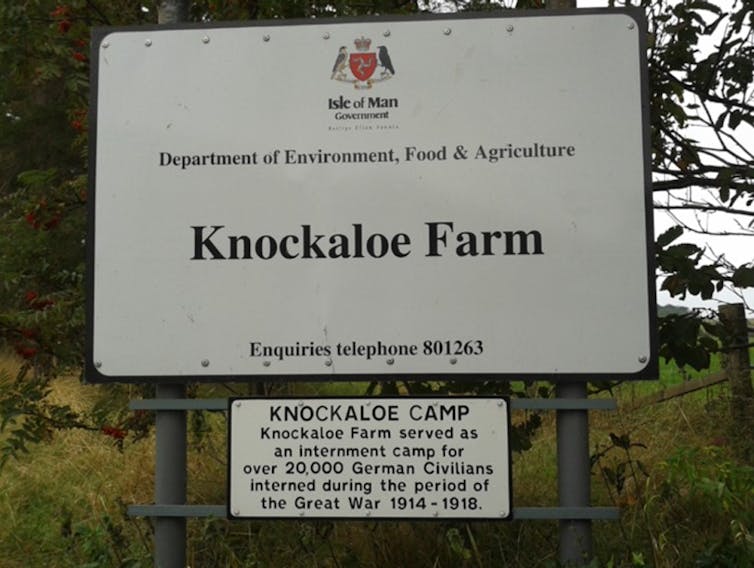

In May 1915 he was interned in the Knockaloe Camp on the Isle of Man – and later in the Lofthouse Camp near Wakefield where he stayed until being sent back to Germany in mid-1918.

30,000 civilian prisoners

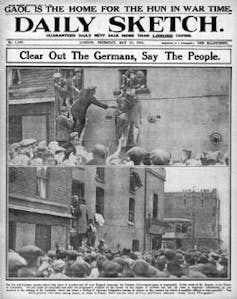

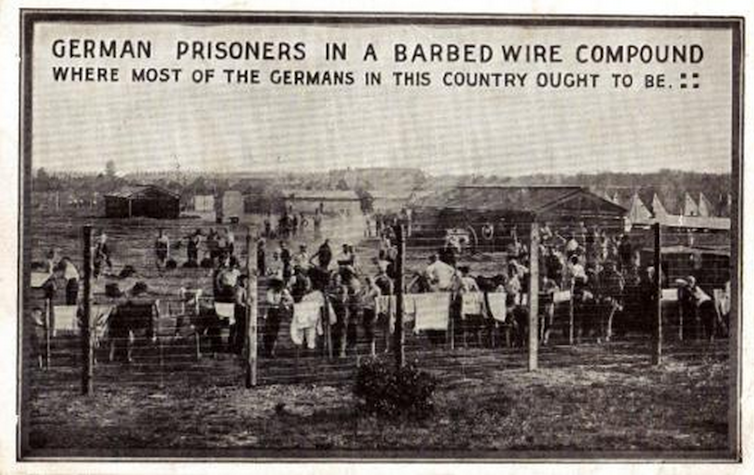

He was far from alone. In 1914, Britain stood at the forefront of organising one of the first civilian mass internment operations of the 20th century. 30,000 civilian German, Austrian and Turkish men who had been living or travelling in Britain in the summer of that year found themselves behind barbed wire, in many cases for the whole duration of World War I. Public opinion supported this, with headlines braying: “The entire country is in the grip of the German octopus”; and “The German Jew in this country was the lowest type of Hun”.

As you drive along a quiet country road near Peel on the Isle of Man, you could quite easily miss the only publicly visible acknowledgement of this civilian mass internment in Britain during World War I.

For those who know where to look, unusual walls on the driveway of the sleepy Knockaloe Farm offer another clue. They are made of the broken-up concrete platforms on which the prisoners’ timber huts were built.

Uncovering this story throws up some uneasy questions about Good Old Blighty during this period. Funny, then, that it has been locked away from public memorialisation, even (or especially) in the full swing of centenary commemorations. As some of the British media are currently busy constructing a new “enemy in our midst” in the form of Muslim minorities, it is imperative that we confront these questions.

Enemy aliens

Friedrich Wiegand, a hairdresser, was another innocent civilian punished by accident of birth. In 1899 he had moved from Saxony to Glasgow, setting up a successful barber’s shop and marrying into a local family. He was detained in the Isle of Man in May 1915, leaving behind his pregnant wife Rebecca and their young daughter. Wiegand was only reunited with his – now enlarged – family in November 1918.

It is no coincidence that both Cohen-Portheim and Wiegand were interned in the crucial month of May 1915. On May 7, the British passenger liner Lusitania had been sunk by a German submarine, killing 1,000 passengers. This sparked a wave of anti-German sentiment in the British public, leading to mass riots against German-owned shops and properties and demands for wholesale internment.

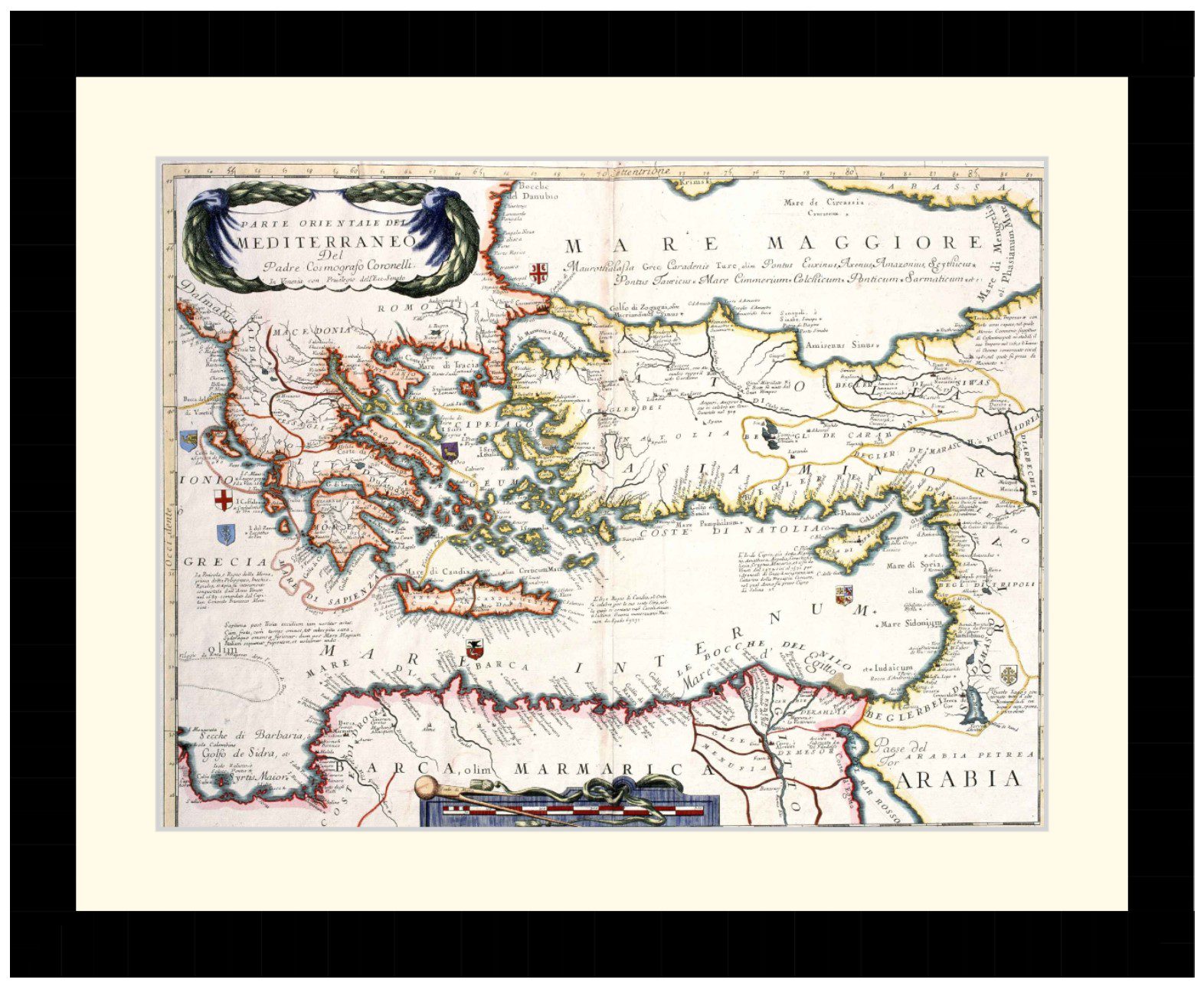

The government – as nervous governments often do – gave a knee-jerk reaction and aggressively pursued a policy of mass internment of male “enemy aliens”, although women and children were excluded. Throughout the British Empire and Dominions there was a multitude of further camps such as Ahmednagar in India, Fort Napier in South Africa, and Holsworthy in Australia. Other belligerent powers pursued similar policies. An estimated 800,000 civilians were held captive throughout Europe.

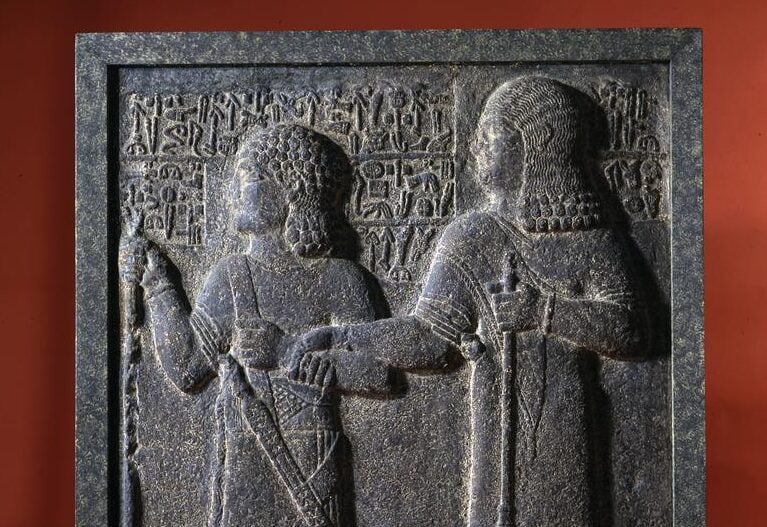

Knockaloe was the biggest of at least 16 civilian camps across the UK. Its 20,000 internees lived in primitive, open-plan timber huts, each holding around 30 people. The vast majority were German subjects, but smaller numbers also came from the multiethnic Austrian and Ottoman Empires.

All camps were surrounded by barbed wire. Work, recreation and education were the only ways to escape the greatest enemy: boredom. Many set up workshops to pursue their occupations, with activities such as shoe-making, tailoring, or hairdressing staving off frustration. Camp schools taught a multitude of subjects. Music, sport and theatre societies sprang up, and camp newspapers – albeit highly censored – reported on day to day life.

All these activities were attempts to avoid the psychological disorder, which we would now recognise as depression, described by the Swiss camp inspector Dr Vischer as “barbed-wire disease”. The incidence of barbed-wire disease amongst inmates was massive, with prisoners often psychologically scarred for life by their experiences.

Never forget?

Britain suffers from amnesia when it comes to this locking up of huge numbers of civilians. The memory doesn’t sit nicely with publicly held perceptions of the Great War and, indeed, British identity. Detaining civilians without any evidence of wrongdoing contravenes any notions of a “just war”. But the war released a deep-seated xenophobia which had been building up over decades, not least since East European Jews had started moving to Britain in the 1880s.

This is not to suggest that the internment policy was born of pure viciousness on the part of the British people and government. But it does demonstrate the power of fear, especially in times of war and conflict. The public were quite understandably concerned by the idea of spies in their midst, especially with their fathers, brothers, sons and friends fighting at the front. This panic spiralled out of control, leading the government to take hasty decisions in an attempt to regain a sense of calm.

Only a generation later, the world was appalled to see that the Holocaust would turn the policy of internment into one of mass extermination. Images of imprisoned Jews dominate our collective memory of 20th-century persecution, and the struggles of interned Germans in Britain in no way compares to this. But this also makes it difficult for us to imagine Germans as victims, even if they were just hairdressers like Friedrich Wiegand, or bakers like V. Fleck, who had a British-born wife and four children – one of whom served in the British army. Or Heinrich Abraham, a German Jew who died in British captivity and is buried in a small graveyard next to the Knockaloe site.

Wiegand, Fleck, Abraham and Cohen-Portheim were just four out of 800,000 civilian internees throughout Europe. Suppressing their memory goes against the very principle of “remembrance”. The centenary commemorations should seize the opportunity to bring their stories to life, not least for the sake of those who might all too easily be labelled “enemy aliens” in the future.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about civilian interment in WW1 Britain

Articles you may also like

Weekly History Quiz No.290

1. How many ships did the Battleship Bismarck sink?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.