Reading time: 6 minutes

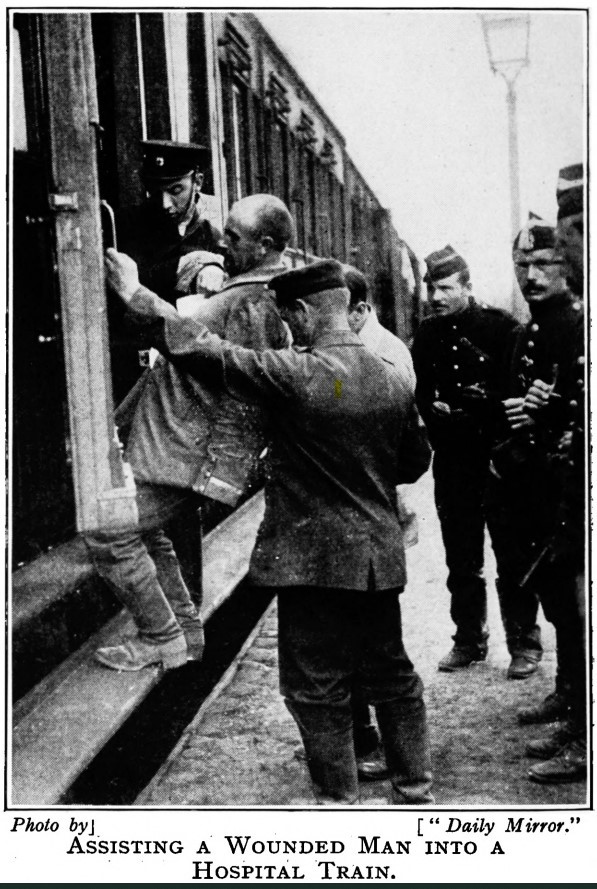

The railways, and the men and women who worked on them, made a significant and varied contribution during the First World War. Some railwaymen joined up to fight, and others helped to run the railways in France and Belgium, delivering men and supplies to the front line. One requirement considered early on in 1914 was the necessity of having to treat sick and wounded servicemen urgently, and the task of moving them away from the Front to hospitals and other places of recuperation.

The answer was the creation of ambulance trains – hospitals on wheels. Such trains were not purpose-built from scratch but instead created from existing rolling stock. They are a striking example of how ingenious adaptation of railway carriages was employed to service a need widely different from the purpose originally intended.

By Chris Heather.

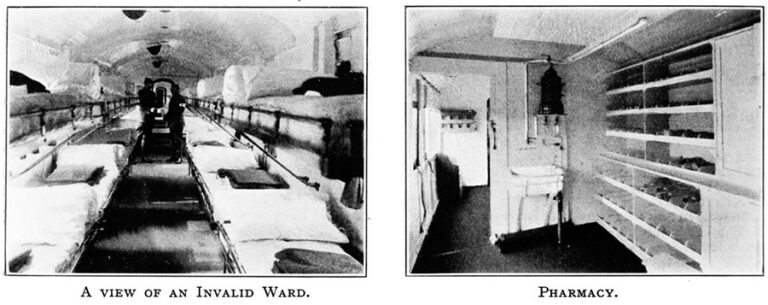

The Great Eastern Railway Company built an ambulance train from nine coaches, five of which were brake thirds (a combination of brake van and third-class carriage), which were converted into hospital wards, each containing beds for up to 20 men. A luggage van was converted into a pharmacy, complete with operating room, while two further carriages were adapted to provide accommodation for medical staff, nurses and attendants, with additional space for stores.

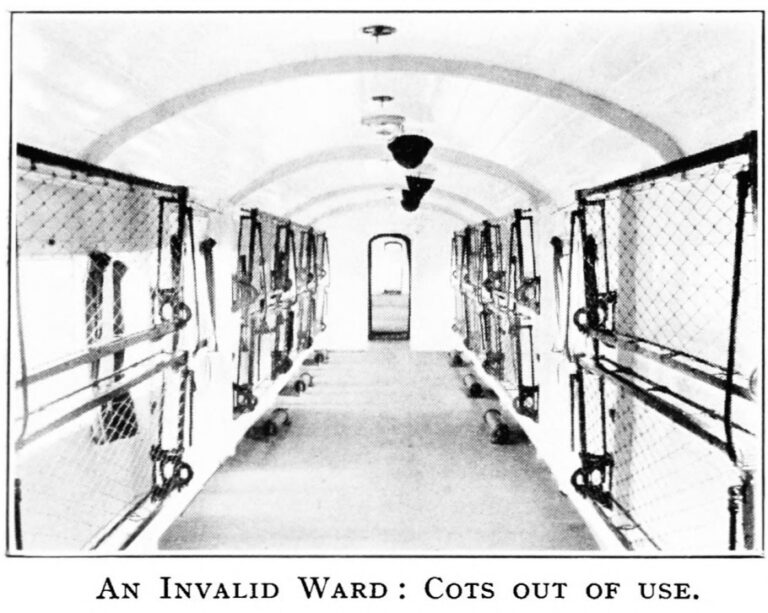

To build the ward cars the whole of the interior of each carriage was stripped of internal fittings, and most of the doors were screwed closed. In to this 50-foot-long ward two tiers of beds, or cots, were installed. Each bed would fold down from the walls of the carriage. In one of the cars fours beds were specially allocated for officers only. The walls were painted white, and green curtains were fitted to the windows. A lavatory and washbasin were provided, as was a strong steam jet used for sterilising equipment. The floor was lead-covered in certain areas, and had linoleum in others.

The Pharmacy car retained the original carriage corridor, but it was widened to allow stretchers to be carried through. There was also a frame of pigeon holes and shelves for storing medical and surgical equipment, and a gas heater for hot water.

Other adaptations included a dining car, fitted with collapsible tables which could be taken down and replaced with beds as required. The whole train was fitted with steam-heated ventilation, with a heater under every bed in the lower tier of each ward car. The lighting was gas powered, and the water supply was provided by a large water tank in the roof above the pharmacy. There was even a telephone system installed.

A large red cross on a white background was painted on the outside of every vehicle in the train, as a sign of the train’s mission of mercy to the sick, injured and disabled.

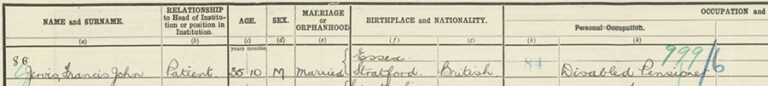

One invalid who may well have used the train was Francis Jervis, originally a booking clerk at Maryland Point (Stratford, East London) on the Great Eastern Railway (GER). He joined the Royal Engineers in February 1915, went to France and made it to Acting Company Sergeant Major before he was so severely wounded in 1917 that he lost the use of his lower limbs, and was partly paralysed in one arm. He was still in hospital when the 1921 Census was taken. However, as reported in the GER Magazine for May 1922 under the heading ‘Determined Invalid’, despite his great physical disabilities Jervis was ‘pluckily’ making the best of it.

Bed-bound and residing at Gifford House Hospital, Roehampton, London, 35-year-old Jervis had obtained a small printing press which he managed to balance on the end of his bed. He had then proceeded to start a small business printing and selling visiting cards, wedding invitations and Whist Drive cards, taking orders from former GER colleagues and elsewhere. The new business provided a useful service, not only to his customers, but to Jervis who, it was hoped, would benefit financially, and to some extent help him forget the unfortunate position in which he found himself. He was producing sets of 50 Gentlemen’s Ivory Visiting Cards for two shillings (Ladies equivalent were 2s 6d), along with headed notepaper and matching envelopes at four shillings for 50 sheets. Requests would be supplied by mail order.

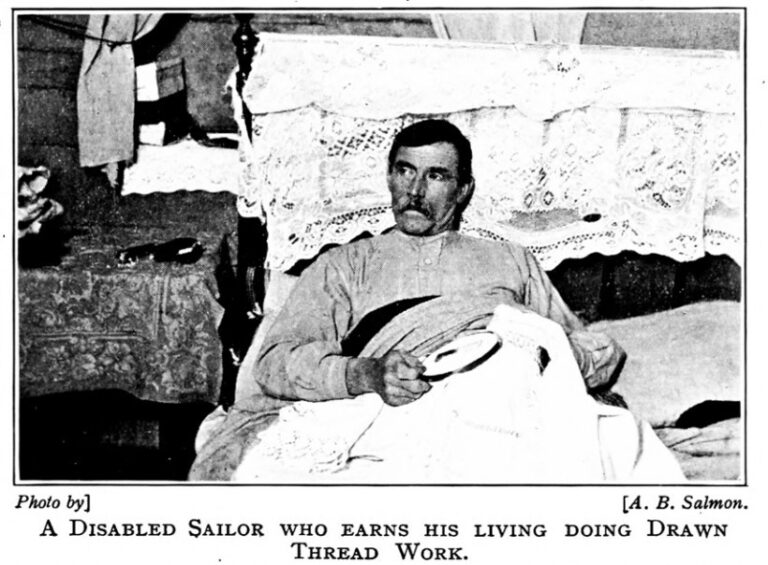

Jervis was not alone in managing to find a useful occupation while confined to bed. Prior to the First World War a sailor named James Watts worked at sea for 12 years, during which time he was shipwrecked twice, once in the Mediterranean and once off the coast of China. Having survived these and other perils he lost the use of both legs in a street accident in London, and his sea-faring career was cut short.

However, Watts did not let his disability stop him using his talents. When in Bombay (Mumbai) he had been fascinated by the skills of local needle workers. He would spend hours watching them, learning their skills, and copying their patterns into a notebook when he got back to his ship, adding designs of his own. He became something of an expert needleman without having received any formal training at all. Following his accident, and finding himself unable to continue a life at sea, he embarked on a new career, undertaking all sorts of needlework and specialising in drawn-thread work. On wet days he would work from his bed, but on sunny days he would wheel himself in his invalid chair to Southwark Park where he could be found working on a dainty brush bag, or a tray cloth in a tambour frame.

It is not known whether he ever drank toast water, an ‘Invalid Drink’ suggested by the Great Eastern Railway Magazine in 1915:

This is just some of the history of disability that the Great Eastern Railway Magazine Periodicals can help us shed a light on. These records are found in record series beginning ZPER here at The National Archives.

This article was originally published in The National Archives.

Podcasts about WW1 ambulance service:

Articles you may also like:

Weekly History Quiz No.255

1. Who painted Liberty Leading the People in 1830?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

General History Quiz 130

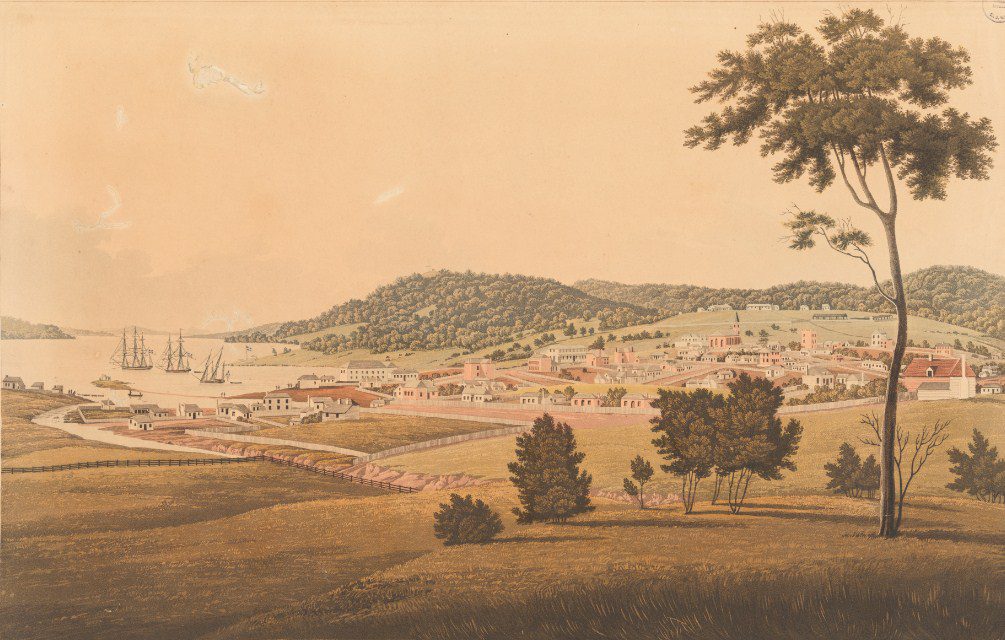

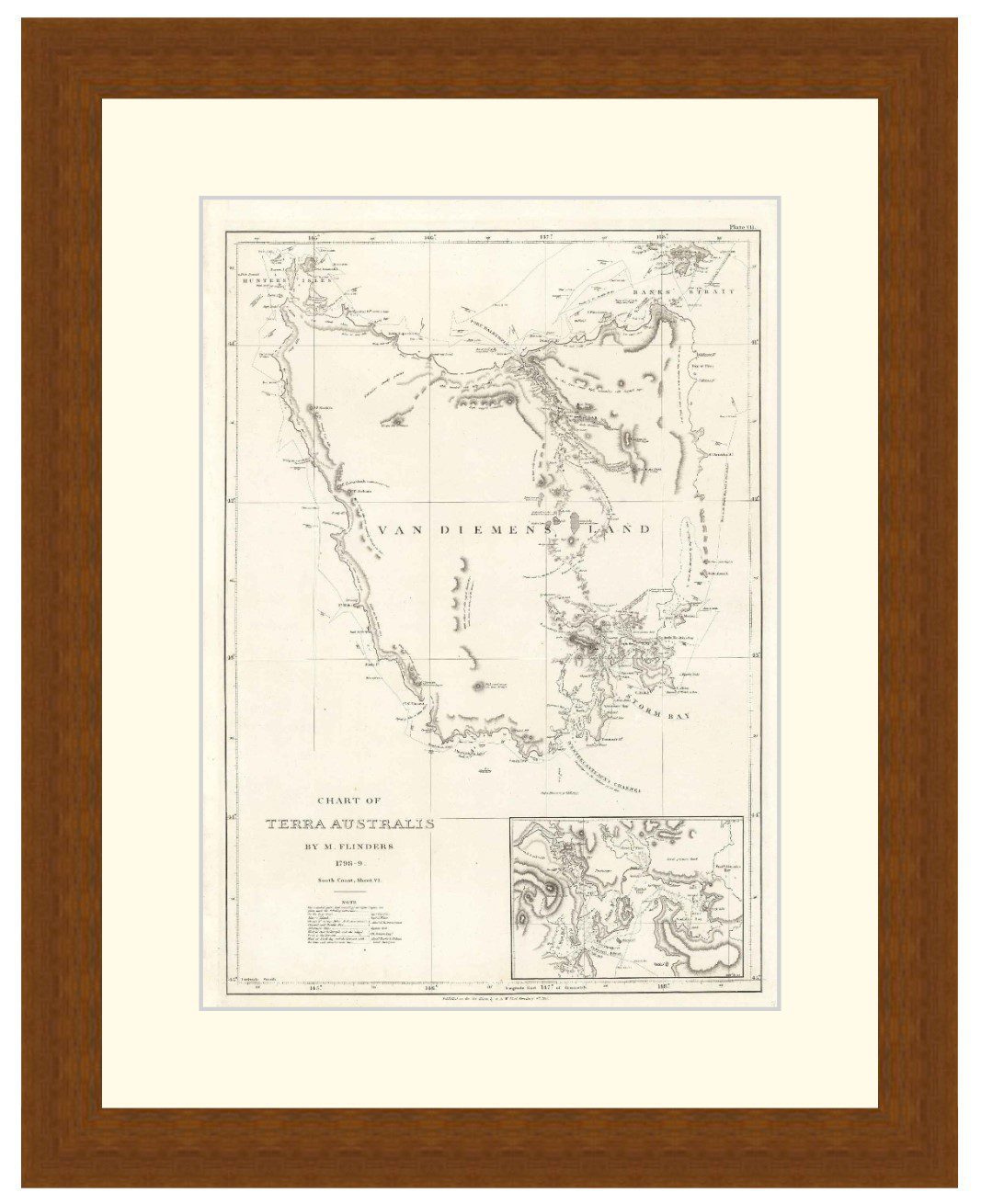

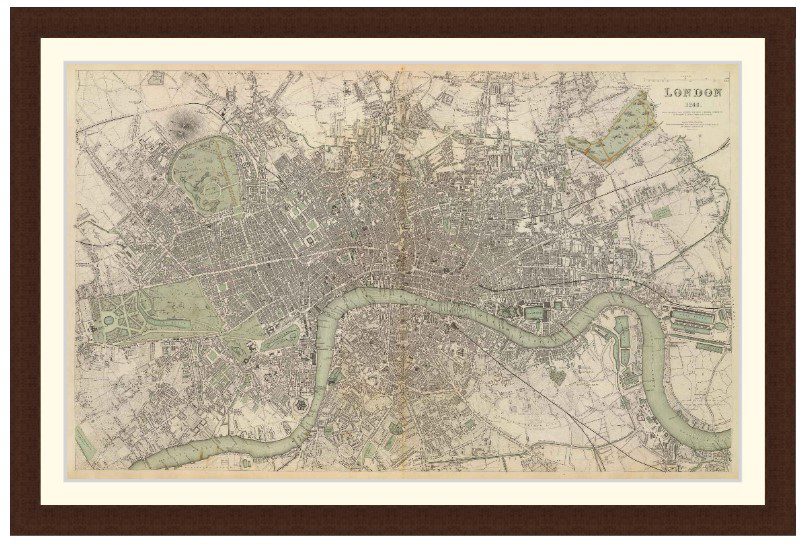

1. Pictured in 1662, which city is this?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

Why Oliver Cromwell may have been Britain’s greatest ever general – new analysis of battle reports

Reading time: 6 minutes

At the age of 43 Cromwell had strapped on his sword for the first time – as a captain of a troop of horses in parliament’s army at the beginning of the English Civil War.

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.