Reading time: 6 minutes

As the eighteenth century came to a close, Dr. Elisha Perkins appeared poised for a truly successful career. He had served his young nation as a surgeon in the Revolutionary War, and even established a private hospital in his own home. He was respected by his colleagues, and stood as a member of the Connecticut Medical Society, which his father had founded.

Still more exciting: in the 1790s, Perkins believed himself to have made an astonishing discovery. During tooth extractions, he noted that patients experienced a brief reduction in pain when their inflamed gums were touched with a metal instrument.

This stands to reason, if the instrument was cold, but Perkins ascribed this effect to some other property of the metal: its supposed ability to “draw off the noxious electrical fluid that lay at the root of suffering.”

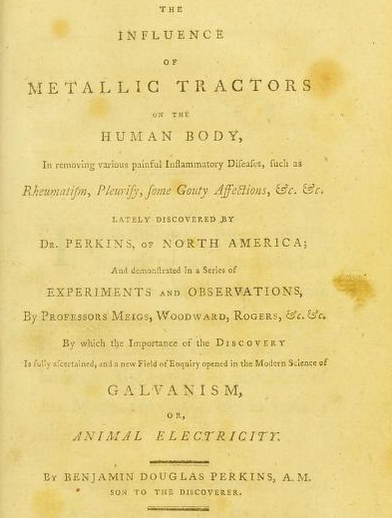

The concept of these ‘electrical fluids’ was related to a fringe theory called animal magnetism, which had already fallen out of favor with the medical establishment. Still, Perkins invested further in his ‘discovery,’ and in 1796, introduced the first medical device to be patented in America, the Perkins Metallic Tractors.

By Mye Brooks

A set of tractors (the term here meaning ‘attractor,’ similar to ‘tractor beam’) consisted of a pair of small metal rods, tapered at one end to a point. These were made of brass and steel, and Perkins promised that rubbing the tractors alternately over sites of pain would relieve a wide range of symptoms, from rheumatism and gout to animal bites and epilepsy.

Historian James Delbourgo describes these tractors as “disarmingly simple things,” which, in the age of ‘heroic’ medical practices such as purging and bloodletting, contributed significantly to the tractors’ massive appeal. And not only were the tractors painless—they were also reusable. Instead of paying for a doctor to visit every time one experienced pain, a person could simply pay once for a set of Perkins tractors and use them over and over.

Another contributor to the tractors’ success was Perkins’ clever marketing tactics. Shortly after the tractors were patented, he brought them before some of the most influential men in America, won their favor, and used their names and testimonials to add an air of legitimacy to his product. He made much of the fact that he had sold a set of tractors to George Washington, for example, and had received an endorsement from then U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth.

The tractors became incredibly popular despite their steep price: twenty-five American dollars, or five guineas when they were introduced to England—over $500 in today’s money. Perkins’ son Benjamin, who relocated to London to sell his father’s invention, wrote “the price at which [Dr. Perkins] offers the Tractors to the Public, the Author conceives cannot be a reasonable cause of complaint. Should they produce their salutary effects… even in one half of the cases in which they shall be employed, Five Guineas must be acknowledged but a very trifling consideration.”

A ‘trifling consideration’ indeed—many people sold off significant parts of their property in order to afford a set of tractors. Said a contemporary, “a gentleman in Virginia sold a plantation and took the pay for it in tractors. Nothing was more common than to sell horses and carriages to buy them.”

Perkins’ runaway success drew the ire of the medical community. A family with a set of Perkins tractors would be less likely to send for a doctor to alleviate pain—so there was a significant financial motive for their disdain. However, much of the dissent came from genuine scientific skepticism. The theory behind Perkins’ tractors had already been debunked: the Connecticut Medical Society decried the principle as having been “gleaned up from the miserable remains of animal magnetism.”

Furthermore, they decided that Perkins’ “delusive quackery… may occasion disgrace to the Society and mischief abroad.” In 1797, Perkins was expelled from the very society that his own father had founded.

Dishonored as he had been, Perkins continued to practice medicine until his death in 1799, when his purportedly miraculous cure for yellow fever failed to do its job.

Marketing for the tractors didn’t fizzle out, either: Perkins and his son only became more predatory. They began to claim that the tractors were made out of secret, exotic metal alloys, when in fact they were still made of ordinary brass and steel. Doctors and ministers might receive unsolicited sets of tractors in the mail with a ‘polite’ request to pay for them if they proved useful.

Benjamin Perkins published pamphlets in England denouncing the Connecticut Medical Society’s decision to expel his father, writing that the vote was “couched in terms which would far better have become the persecutions of a Copernicus and a Galileo, in an age of ignorance and superstition, than those who would be fondly considered as the patrons of science and philosophy in the enlightened era of the eighteenth century.”

He even went so far as to secretly commission a political cartoon that lampooned the tractors, perhaps abiding by the principle that all publicity is good publicity.

Still, just as the Perkins family persisted, so did the medical establishment. In 1799, a well-regarded English doctor called John Haygarth conducted a series of experiments to test the efficacy of Perkins tractors. One day, he treated several rheumatic patients with the tractors. A large percentage of them reported a reduction in pain. The next day, Haygarth repeated the procedure—but this time, using pieces of wood painted to look like genuine tractors. The same patients reported the same reduction in pain.

Haygarth had shown “to a degree which has never been suspected, what powerful influence upon diseases is produced by mere imagination.” These experiments were the first genuine scientific documentation of what’s come to be known as the placebo effect, and our understanding of it helps us to determine whether new medicines actually work.

Thus, the quack doctor’s scheme unwittingly gave rise to the knowledge that’s defeated a slew of charlatans since. Still, medical scams continue to arise, and continue to harm those who have not learned from this history. Wrote Lord Byron, “what varied wonders tempt us as they pass! / The Cow-pox, Tractors, Galvanism, Gas / in turns appear to make the vulgar stare / ‘till the swoll’n bubble bursts–and all is air.”

Podcasts about Medical Scams throughout History

Articles you may also like

The Long Tail of the First World War

Fallen Empires and Civil War By Caitlan Hester The popular view of the First World War is that it ended with Armistice in 1918. But the end the First World War did not put an end to conflict and combat. The 1918 Armistice was followed by events that radically shaped today’s geo-political landscape: the spread […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.