Reading time: 4 minutes

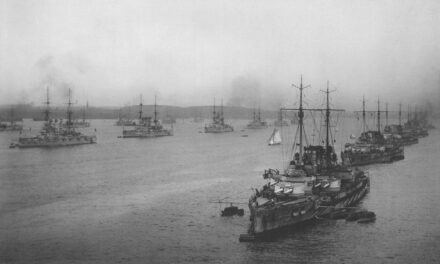

When Allied troops stormed the beaches at Normandy, France on June 6, 1944 – a bold invasion of Nazi-held territory that helped tip the balance of World War II – they were using a remarkable and entirely untested technology: artificial ports.

To stage what was then the largest seaborne assault in history, the American, British and Canadian armies needed to get at least 150,000 soldiers, military personnel and all their equipment ashore on day one of the invasion.

By Colin Flint, Utah State University

Reclaiming France’s coastline was just the first challenge. After that, Allied troops planned to fight their way across the fields of France to liberate Paris and, finally, onto Berlin, where they would converge with the Soviet army to defeat Hitler.

When Gen. Dwight Eisenhower and his advisers pressed for this ambitious invasion of Nazi-occupied France, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was dubious.

Could it be done?

Such an operation would require more than a million soldiers – all equipped with weapons, ammunition, food and clothing – plus hundreds of thousands of vehicles, tents and medical personnel.

Getting so many people and materials from ship to shore while battling waves, tides and currents presented an enormous logistical challenge.

Churchill, recalling the failed marine campaign to capture Gallipoli during World War I, feared that Allied troops would get trapped on the beaches and be sitting ducks for the German soldiers awaiting atop Normandy’s cliffs.

So Churchill demanded that a team of engineers, scientists and military officers design a marine staging area that could actually support a successful operation.

The team’s solution was ingenious: two easy-to-assemble artificial ports where Allied ships could safely anchor to stage the massive operation.

As I write in my 2016 book on what became known as the “Mulberry Harbours,” each of these artificial ports consisted of artificial breakwaters – barriers against waves made up of sunken ships and huge concrete chambers.

Behind the circular breakwaters was a sophisticated system of floating piers anchored to the seabed.

All of these parts were towed 30 miles across the English Channel on D-Day from southern England, then sunk into place, about a mile off France’s northwest shore, the same day.

German planes doing air reconnaissance did spot the concrete chambers, which had been filled with air to make them float before they were sunk. But, according to my archival research, they had no idea what they were seeing or how these giant containers would be used.

A floating solution

Once complete, each Mulberry Harbour – a code name that has no deeper meaning – gave Allied troops about 1 square mile of quiet, wave-free ocean from which to stage the invasion.

Nearly 200 military ships and landing crafts anchored at Mulberry Harbours in their first week, sending 12 military divisions, or about 180,000 men, straight into enemy territory.

Ten thousand of them were killed or injured on the first day, blown up by landmines and picked off by camouflaged German machine gun nests and blasted by artillery in concrete bunkers.

On June 19, 1944, a storm permanently disabled the Mulberry Harbour used by the American armed forces.

But Britain’s Mulberry Harbour continued to serve Allied forces for another 10 months as they freed all French ports from German control.

War games in the bath

Churchill became convinced of the merit of the Mulberry Harbours design while in a bath tub on the Queen Mary, as he traveled to Washington to discuss war strategy with President Franklin Roosevelt in 1943.

Churchill’s scientific adviser, Professor John Bernal, floated paper boats in the prime minister’s bathtub, agitating the water to simulate waves, then used a loofah, or sponge, to demonstrate the pacifying effect of breakwaters.

Churchill, who often worked while bathing, saw in that Queen Mary bathtub the answer to the challenge he had issued in the 1942 memo commissioning portable harbors for D-Day.

“They must float up and down with the tide. The anchor problem must be mastered. Let me have the best solution worked out,” Churchill wrote. “Don’t argue the matter. The difficulties will argue for themselves.”

After D-Day, some Mulberry Harbours engineers were sent to the South Pacific with the idea that similar portable ports would be needed for the invasion of Japan. The atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki made that unnecessary.

No similar wartime engineering feat has been tried since.

This article was originally published by The Conversation.

Podcasts about Mulberry Harbours:

Articles you may also like:

How plague helped make Rome a superpower

Reading time: 7 minutes

That Rome prevailed and would go on to conqueror the Mediterranean world was perhaps in no small way due to the tiny bacteria or virus that destroyed Himilco’s army outside Syracuse in the autumn of 212.

The Battle for Crete: Hard Fought

Reading time: 8 minutes

Wherever they fought in the Second World War, Australian troops acquitted themselves well. They escaped the clutches of the Afrika Korps in the Benghazi handicap and soon after helped hold back Rommel at the second battle of El Alamein. Even certain defeat couldn’t stop Australian troops, like in Crete, where they and their New Zealand counterparts fought a rearguard action that delayed the German war effort considerably.

Finding Your Ancestors: Researching Aboriginal Family History in NSW

Most Aboriginal people are already historians. They hold knowledge of family ancestry, culture and history, and often treasured family photos and documents. There is much more to find online and in libraries and archives, but if you haven’t searched in these places before, it can be a bit hard to know where to start. Finding Your […]

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.