Reading time: 6 minutes

In the early decades of the 20th century, modernism forever changed artistic representation. Artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, whose experiments formed the foundations of Cubism, were just some of the many innovators responding to changes in technology and urbanization.

Picasso is possibly one of the most well-known artists today, and much is known about his life and inspirations. However, one influence behind his innovative style is less explored in popular culture—the impact of colonialism. The cubist movement arguably would not be what it became without the legacies of colonialism and imperial conquest.

By Madison Moulton

The Rise of Cubism

Although it may be hard to imagine today considering how ubiquitous cubist art became in the modernism canon, the movement was a radical break from centuries of artistic tradition, built on the foundations of earlier modern artists like Cezanne. In essence, cubists reimagined reality and representation in art by displaying objects from multiple viewpoints simultaneously.

Picasso and Braque were at the forefront of Cubism, creating a new visual language of interlocking geometric shapes and subdued color palettes that shocked the art world. This approach reflected a broader shift towards abstraction and reinterpretation, a visual metaphor for a rapidly changing world.

Cubism challenged viewers to reconsider their assumptions about form, perspective, and the nature of reality itself, a challenge that was not always welcomed by critics.

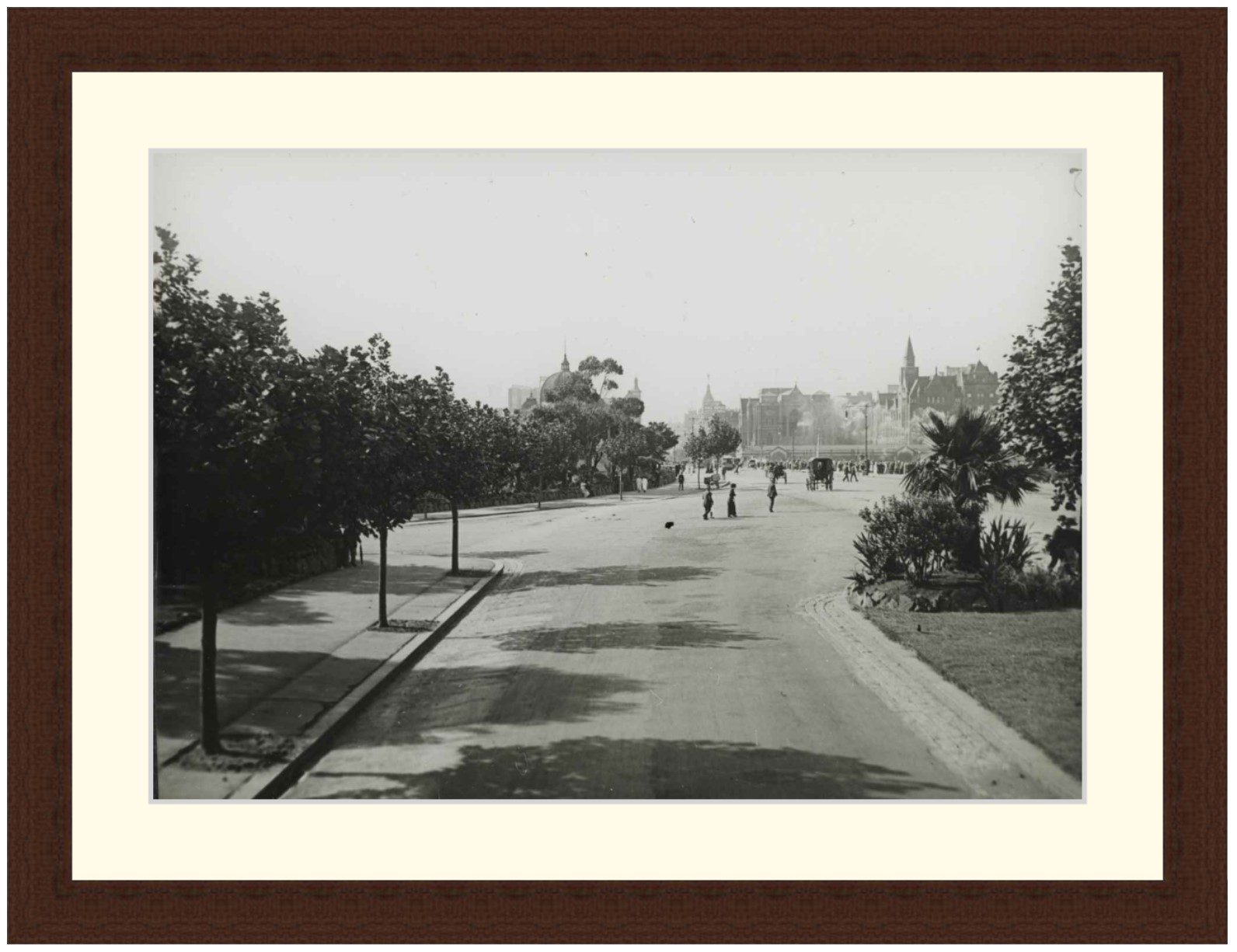

Colonial Encounters in Paris

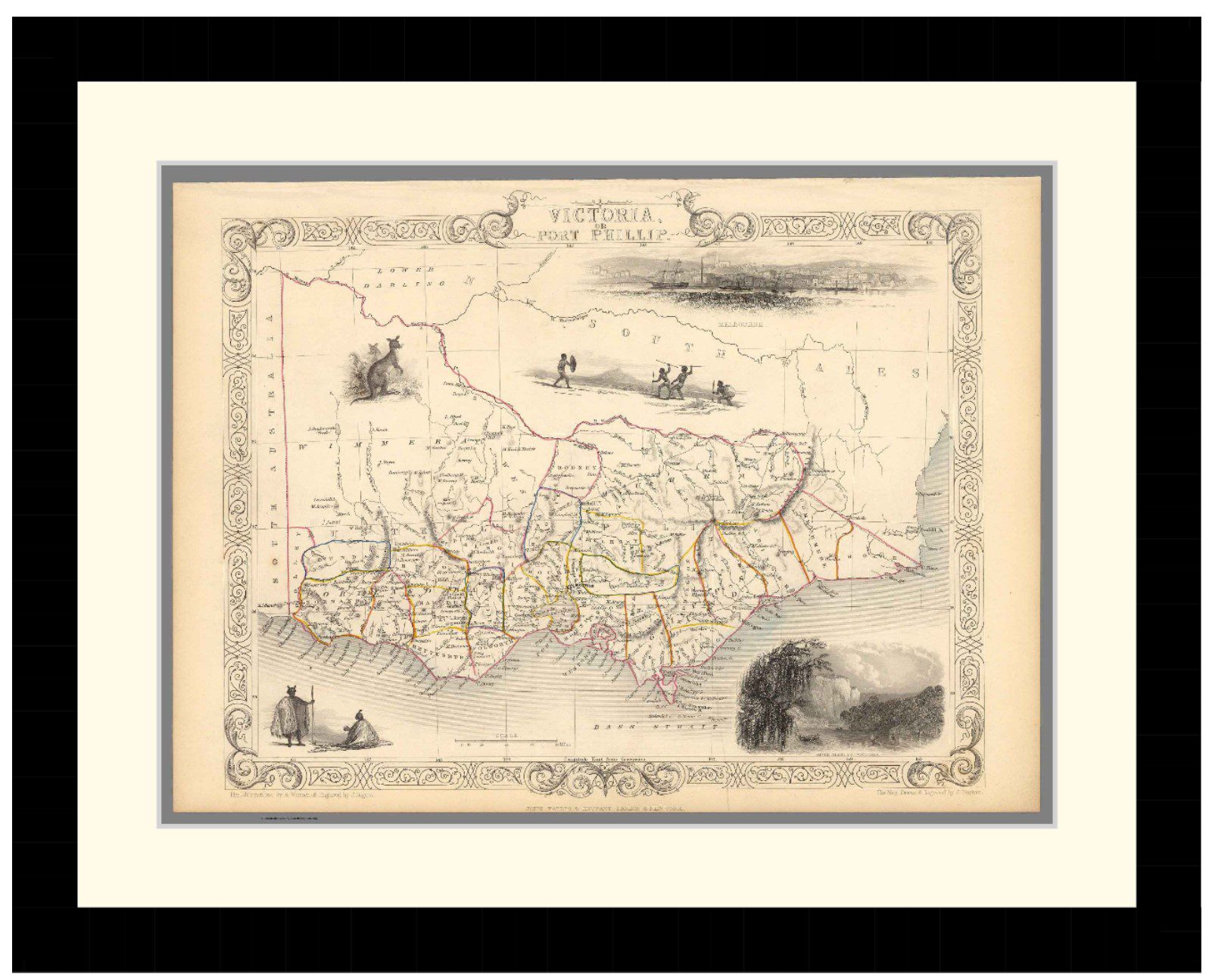

During this era of artistic experimentation, Paris was a hub of cultural innovation and urbanization supported by colonial conquests abroad. The 19th century witnessed extensive French colonial ventures in West Africa. One of the many consequences of this occupation was the thousands of African objects that were stolen and exported to Europe.

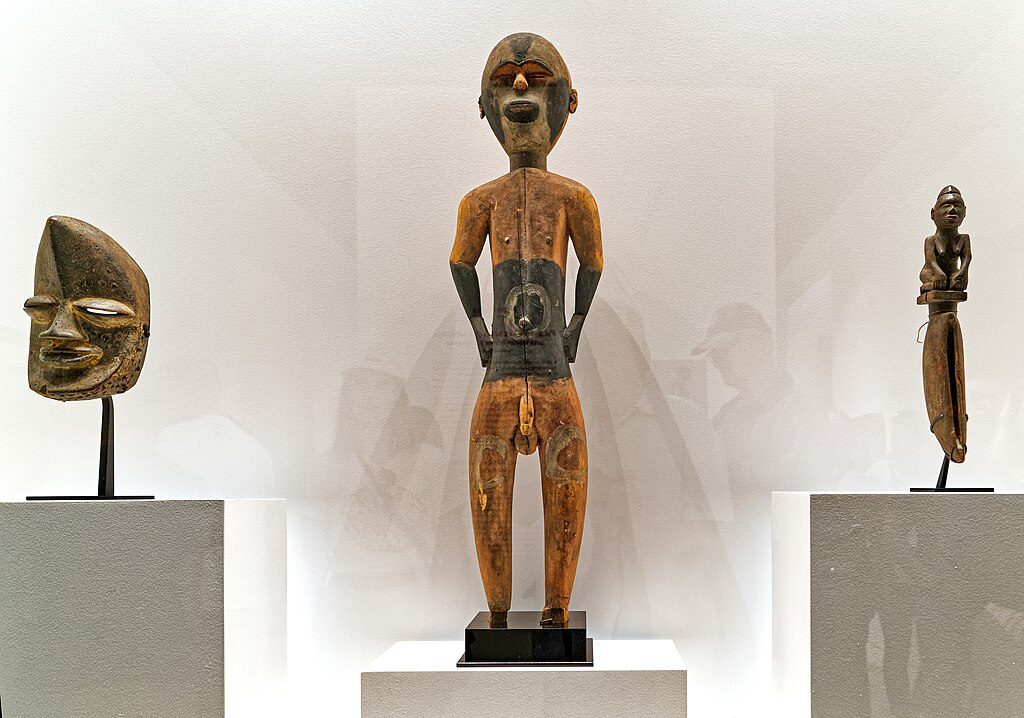

Ethnographic museums in Paris like the Palais du Trocadéro, became repositories for these objects, which were displayed as ‘artifacts’ and relics of an exotic, ‘primitive’ world. Not appreciated as art forms embedded in their native cultures, these objects were stripped of their original context and presented as evidence of a universal, static idea of African identity.

The colonial mindset saw these works as symbols of a supposedly unchanging and simplistic ‘Other’, reinforcing cultural ideas popularized at the time by works like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. They were valued for their novelty and the exotic allure they lent to European collections, supporting a narrative that fueled imperial conquest and cultural domination.

It was at one of these ethnographic museums that Picasso found inspiration for his cubist artworks.

Picasso and African Art

A defining moment in Picasso’s artistic journey came during his visits to the ethnographic museum at the Palais du Trocadéro. He moved through displays of African masks and sculptures, inspired by their representation of the human form. Captivated by the abstract forms and the perceived simplicity they conveyed, he began to integrate these visual elements into his own evolving style. Of the masks at the museum, he said they encouraged him to “liberate an utterly original artistic style of compelling, even savage force.”

It was not the cultural narratives or histories behind these objects that interested Picasso. How the objects arrived in front of him was of little consequence, as was expected at the time. Rather, he was drawn to their formal qualities (in an artistic sense). The angular lines, expressive forms, and innovative use of space were the liberating tools for reimagining artistic representation that he was searching for.

This inspiration was evident in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), one of Picasso’s most famous works and arguably the first cubist painting. The mask-like faces of the figures unmistakably echo the aesthetics of African art. This followed a broader trend of ‘primitivism’ in art, an idealisation of so-called ‘primitive’ cultures and periods in history. The phrase is often tied to Paul Gauguin and his Tahitian paintings, but certainly applies to Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. The period from 1906 to 1909 became known as Picasso’s African period, but the influence of African art persisted in his later works too, and in the cubist movement as a whole.

Interestingly, Picasso did not always admit to this influence. He initially claimed he was not aware of African art at the time of painting Les Demoiselles, but later described seeing African masks as a “revelation” that fuelled the painting’s formulation. Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler’s recalled seeing “African sculptures of majestic severity” in Picasso’s studio 1907, evidence that we shouldn’t take an artist’s words at face value.

Perceptions in Paris

The debut of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was a shock in the Parisian art world. It was first exhibited at the Salon d’Antin in July 1916, and generally deemed immoral. The style of the figures and subject matter sparked major controversy, an uproar that cemented the work in the history of modernism.

The angular features and mask-like visages in the painting bear a direct visual connection to the objects displayed in ethnographic museums. Although none have been directly linked to specific objects displayed at the time, it’s clear they had an impact on the work. The development and adjustments made to preliminary drawings reveal more (look at The Philosophical Brothel by Leo Steinberg if you’re interested in the evolution of the work).

In recent years, a more nuanced understanding of Cubism and African art (and colonialism, although less so) has emerged. Modern reframing involves recognition of two things: celebrating the important and dramatic influence African art had on modernism while also confronting the realities of how these objects were acquired, categorized, and decontextualized by colonial powers.

Picasso’s works invite a conversation between innovation and exploitation, a dialogue that continues to shape our understanding of art, history, and the politics of imperialism.

Articles you may also like

How the Ancient Egyptian economy laid the groundwork for building the pyramids

Reading time: 5 minutes

In the shadow of the pyramids of Giza, lie the tombs of the courtiers and officials of the kings buried in the far greater structures. These men and women were the ones responsible for building the pyramids: the architects, military men, priests, and high-ranking state administrators. The latter were the ones who ran the country and were in charge of making sure that its finances were healthy enough to construct these monumental royal tombs that would, they hoped, outlast eternity.

Dag Hammarskjöld: a defiant pioneer of global diplomacy who died in a mystery plane crash

Reading time: 5 minutes

The idea of a global institution has captivated thinkers since Immanuel Kant in the 18th century. But a body set up to create and maintain world peace and security needs the right people to make it work. When the United Nations was created in 1945, old sentiments — seen in the disbanded League of Nations — threatened to prevail. Would the UN and its leadership simply comply with the great powers of the day?

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.