Reading time: 10 minutes

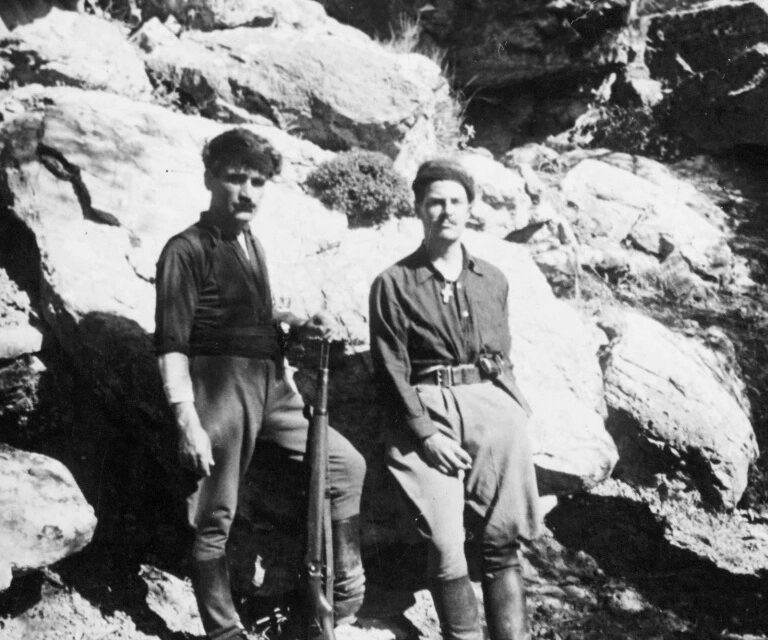

One of the more impressive feats of arms during the second World War was the way in which the people of Crete fought a guerrilla campaign against the German occupation force. With help from the allies, the Cretans — men, women and even children — fought a brutal and bloody campaign against the invader. In this article, we look at what happened through the eyes of some of the people who participated, Cretan, British and Australian.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

In June 1941, after the fierce battle of Crete, the island had fallen into the hands of the Germans. The Commonwealth troops on the island had managed to fight a bloody rearguard action to get as many onto Royal Navy transport ships, but in the end only roughly 19,000 made it to safety in nearby Egypt.

Capture and Evacuation

That left about 12,000 men and their materiel on the island. Most of the men surrendered or were captured by the Germans, though some gave the invader the slip and escaped into the mountains of central Crete, helped by local villagers. For example, one Australian veteran, Frank Reiter from Meeniyan, Victoria, was on the run for six months in the Cretan mountains, moving around until he got news he could be evacuated.

About 100 other men, including some Australians, were rescued in July 1941, only a few weeks after the last evacuation ship had left Crete. Lt. Commander F.G. Poole of the submarine HMS Thrasher landed near Limni in western Crete and made contact with a local monastery’s abbot, saying he came to rescue 100 men.

The cleric was at first suspicious of Poole, but eventually was convinced of his good intentions and sent news to all the surrounding villages to find as many British soldiers as they could (most Greeks called all allied troops “British”). The next night, the men made their way to the monastery, where the abbot fed them and then made their way to the beach where Poole was waiting with his submarine. Though the source doesn’t make clear how many he rescued, they made clean their escape.

Reg Saunders, who went on to become the first Aboriginal commissioned officer in the Australian Army, as well as fighting with distinction in the Battle of 42nd Street, managed to evade on Crete for 11 months. He was assisted by the local Cretans, who provided him with civilian clothes and taught him the language. Saunders was among a party of men evacuated from Crete by a British submarine in May 1942.

Fight, Not Flight

A handful of Commonwealth troops would even join the Cretan resistance as they fought against the German garrison, bolstered by help from London in the form of operatives from the Special Operations Executive, Churchill’s “Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare.” In the end, these resistance cells would grow so strong as to be able to wage a full-blown guerilla war in the mountains of Crete.

This guerrilla war is the subject of the independent documentary The 11th Day and we draw from that film for some of the testimonies in this article. We also draw liberally from the Australians at War Film Archive, a massive treasure trove of information we’ve drawn from many times for our Australians in the Mediterranean during WW2 series.

The SOE’s role in the guerrilla war was mainly intelligence and coordination, at no point were there more than a handful of officers on the island, with maybe a few regular soldiers left over after the evacuation. The brunt of the hard work fell to the Cretans themselves, who stepped forward in impressive numbers, with the men doing the fighting, the woman handling the logistics and children acting as couriers.

Even when they weren’t actively involved in the fighting, the Cretans helped in other ways, like with feeding and hiding Commonwealth troops on the run. Most of them lived rough in the mountains or holed up in villages. In the words of Vasilis Spahis, a young boy at the time, “we idealised the [British soldiers], any time we heard there was a British soldier around, we would go and help him.”

Mr. Reiter for his part recalls how villagers would sneak into the mountains at night to feed him and his mates. “I can’t speak highly enough of [the Cretans] they helped us out with what they had […] you know they were really good.”

German Reprisals

Helping British and Commonwealth soldiers was dangerous, though, and the Germans were renowned for carrying out reprisals when they found soldiers hiding somewhere. For his part, Mr. Reiter never stayed in the villages for that very reason, because of the risk it posed to the people living there.

According to him, one Australian soldier was found living in a village during a German raid and, in his words, “they took it out on the village. I can remember seeing one village completely surrounded by troops, they rounded everybody up, shot all the blokes and burnt the village to the ground.”

Atrocities like Mr. Reiter describes weren’t unique. According to Michalis Anastasiades, all the people in his village were marched to a nearby creek and asked whether they had helped the British during the invasion. Depending on how they answered, they were divided into two groups.

With all the villagers “sorted,” the Germans started shooting the men who had helped the British. One man, who was only wounded by the rifle fire, lay on the ground crying with his hand outstretched until, according to Mr. Anastasiades, “a German walked up to him with a pistol and shot him in the head.”

This kind of slaughter would become commonplace in Crete, but, much like anywhere else in occupied Europe, it only turned the local population against the Germans even more. As a result, when SOE operatives like Patrick Leigh Fermor — who was interviewed for The 11th Day — arrived to coordinate the evacuation of remaining troops, they found, in Fermor’s words, “fertile ground” for organizing a full-blown guerrilla army.

Escalation

Fermor had been selected for service in Crete because he spoke Greek, as a young man he was quite an adventurer and had travelled on foot throughout the region. However, it wasn’t like London had a very strict plan about what to do except evacuate as many men as possible. As such, Fermor says he and his colleagues were “very free to do what we wanted.”

Fermor quickly became something of a celebrity in Crete. According to Giorgos Dondoulakis, who fought alongside him, Fermor was an “amazing character.” Fermor would stop German soldiers on patrol, ask for a light for his cigarette, and even ask how things were going. All the while he’d size up their weapons and insignia and use that valuable information when planning their next action.

There was plenty of action to be had, too: the Cretan resistance’s main aim, inspired by London, was to sabotage the island’s airfields and thus starve the German garrison of supplies. The Cretans carried out several successful raids that severely hampered the occupiers’ logistics.

The Germans weren’t taking this lying down and they further escalated their terror campaign. However, to do so, they needed to move deeper into the mountains and find the villages where the guerrillas were holed up. This turned out to be a mistake as, in the words of Manolis Tzikritzakis, “the Germans were confused in the mountains, in the mountains [they] were nothing.”

Hit and Run

The guerrillas made good use of this and ambushed the Germans whenever they could. The most significant engagement was the Battle of Trahili, a ridge near the village of Vorizia, where a resistance group under the command of Giorgos Petrakis — a famous guerrilla leader more commonly known as Petrakogiorgis — managed to escape German encirclement, losing only seven men, and inflicting as many as 33 casualties on the Germans.

However, in retaliation, the Germans ended up committing one of their worst acts of the entire occupation, the destruction of Vorizia by aerial bombardment. In the words of Fermor, “the whole palace was a pillar of smoke, it was a horrifying holocaust.”

The Final Act

In 1944, Fermor had his most audacious idea of all, to capture and abduct the German commander of Crete, General Kreipe. The full story is described very well here as well as Fermor’s own book Abducting a General, but the short version is that Fermor assembled a team of SOE operatives and Cretans, ambushed the general’s car and then drove off with it.

They abandoned the car in the mountains, left a note about how sorry they were to leave the car behind, and then marched their prisoner across the island to a waiting transport, which brought him to Egypt where he was debriefed.

This was also the crowning achievement of the SOE’s activities in Crete: a few months later, the Germans abandoned Crete, too exhausted to hold on to the small untameable island. Fermor’s name lives on in Cretan folklore, as do the actions of all the men who fought to free the island.

We recommend that anybody interested to know more about this subject check out the documentary The 11th Day for themselves on its website; it costs $9.95 to stream for three days.

This project commemorating the service by Victorians in the Mediterranean theatre during WWII was supported by the Victorian Government and the Victorian Veterans Council. Sign up to the newsletter at the bottom of the page to be notified when the next article in this project is released.

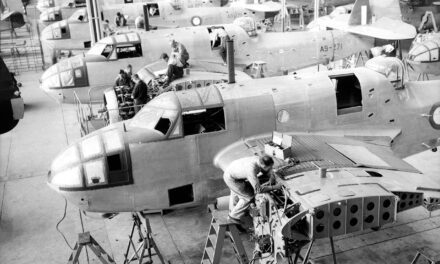

3 Squadron RAAF – Podcast

As the Allied armies fought across North Africa, first against the Italians and then the Vichy French and Rommel’s Afrika Korps, one squadron of the RAAF was there from the beginning. No. 3 Squadron was the first RAAF squadron to leave Australia and played an important part in many of the important battles from 1940 to 1943 across North Africa, Tunisia and Sicily.

The Battle for Crete: Hard Fought

Reading time: 8 minutes

Wherever they fought in the Second World War, Australian troops acquitted themselves well. They escaped the clutches of the Afrika Korps in the Benghazi handicap and soon after helped hold back Rommel at the second battle of El Alamein. Even certain defeat couldn’t stop Australian troops, like in Crete, where they and their New Zealand counterparts fought a rearguard action that delayed the German war effort considerably.

Battle of 42nd Street – Anzacs Proving Germany Could be Beaten

Morale can make all the difference on the battlefield. On the 27th May 1941, with the Greek island of Crete close to loss and the Allies in full retreat, a 12 minute moment of madness by Australian and New Zealand troops proved that aggression and bravery could overcome Germany’s elite troops. By Richard Shrubb. Background […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.