Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

When marking the centenary of the terrible events of 1917, some of the most devastating of World War I, it is perhaps understandable that the British have focused their attention on the Passchendaele offensive and the Americans on their entry into the war against Germany. Unfortunately, their desire to commemorate the heroism of their own service personnel often has an ugly flip-side: the denigration of the courage and skill of their French allies.

By Gervase Phillips.

This attitude is best captured in the phrase “cheese-eating surrender monkeys”, coined in a 1995 episode of The Simpsons and popularised by journalist Jonah Goldberg in a 1999 column for The National Review. It suggested, among other things, that the French “surrendered Paris to the Germans [in 1940] without firing a shot”.

Doubtless the piece was satirical in intent, but the seriousness of the underlying prejudice became all too obvious in 2003; witness the invective directed at the French by US and British politicians and media following France’s (retrospectively, wise) decision not to support military intervention in Iraq.

If the British and Americans are serious about remembrance, then let’s remember France’s military performance fairly.

Be fair on the French

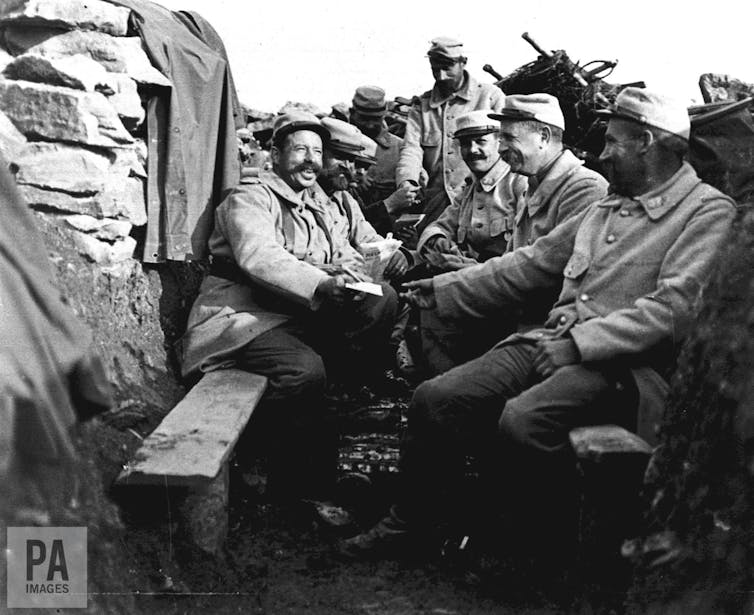

From August 1914 to early 1917, it was the French Army that bore the brunt of the fighting on the Western Front – and with astonishing stoicism. In one two-week period – August 16-31, 1914 – they suffered 210,993 casualties. By comparison, British casualties numbered 164,709 in the opening month – July 1916 – of the Somme offensive.

The French Army also adapted effectively to the challenges of trench warfare, perfecting artillery “barrage” fire and pioneering innovative platoon-level infantry tactics, centred on automatic weapons and rifle grenades. While the first day of the Somme – July 1, 1916 – was a disaster for the British, the French took all of their objectives.

In early 1917, 68 French divisions suffered mutinies. But the soldiers taking part in what were effectively military strikes neither refused to defend their trenches nor abandoned France’s war aims. The army itself rallied magnificently from this near collapse and played a pivotal role in the Allied victory of 1918. From July to November 1918, French troops captured 139,000 German prisoners. In the same period, the American Expeditionary Force captured 44,142 Germans.

In the interwar years, the French invested heavily in massive defensive fortifications, the Maginot Line, along the Franco-German frontier. This decision has often been derided as indicative of a defeatist attitude. Yet France had a smaller population than Germany and could not hope to match its field army in size. Fortresses could make good the deficiency. The key point of the Maginot Line was to protect France’s industrial heartland from a rapid German offensive and funnel a German invasion through Belgium. It worked.

The German Army won the ensuing campaign in May and June 1940, through its audacious “sickle cut” through the Ardennes Forest, which was thought impassable by Allied commanders. This cut off the British, French and Belgian armies to the north and doomed them to defeat.

French strategic planning must bear much of the blame for this catastrophe, yet this was an Allied defeat, not simply a French one. The Dutch and Belgians had been reluctant to risk their neutrality and so there was little coordination before the Germans struck. And the British clearly assumed that France was to bear the main brunt of any land fighting.

The British Expeditionary Force of 1940 had a maximum strength of just 12 divisions. In 1918, it had numbered 59. Small wonder that the Nazi propaganda machine used to taunt their enemies with claims that the British were “determined to fight to the last Frenchman”.

The Dunkirk ‘miracle’

Although their generals were outclassed in 1940, French troops fought courageously and skilfully. For example, at the Battle of Gembloux – May 14-15, 1940 – elements of the French First Army checked the vaunted German “Blitzkrieg” and won enough time for their comrades and allies to withdraw. Without such tenacious rearguard actions, there would have been no “Miracle of Dunkirk” and the war might have been lost in 1940.

Having crossed the Meuse River, the German Panzer divisions only had to advance 150 miles to the Channel coast to trap the bulk of the Allied forces – 1.8m French soldiers were captured, and 90,000 killed or wounded.

In the opening phase of Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union the following year, the Red Army suffered nearly 5m casualties, including 2.5m who surrendered. The Russians also lost 600,000 square miles of territory. Yet, as Charles De Gaulle observed to Stalin, in the aftermath of this colossal defeat, the Soviets still had 5,000 miles of Eurasia into which they could retreat. The French did not lack courage in 1940; they lacked space.

The French military contribution to Allied victory in World War II did not end in 1940. There were 550,000 Free French soldiers under arms in 1944 and they made a major contribution to the liberation of Western Europe. In particular, Operation Dragoon – the invasion of southern France in August 1944 – was effectively a Franco-American operation, with limited British involvement.

Many of the French soldiers involved were recruited in France’s African colonies, but this was no different to the British reliance on 2.6m Indian soldiers to support their empire’s global war effort. By all accounts, the French units serving in Italy and Western Europe between 1943 and 1945, fought well, in the best traditions of the French Army.

Cheese-eating surrender monkeys? It’s time to think again.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Articles you may also like

In their own words: letters from ANZACs during the Gallipoli evacuation

Just five days before Christmas, in the early hours of Monday December 20, 1915, the last Anzac troops left Gallipoli in what Australian historian Joan Beaumont called an “elaborate game of deception”. Self-firing guns were rigged to take pot-shots and camp fires lit to give the impression of there being more soldiers than there were. The Australians […]

The Somme: The German perspective

By Dr Robert T. Foley. How do Germans view the Battle of The Somme? This article explores reactions to the most famous battle of the First World War. Shortly after daybreak on 1 July 1916, around 100,000 troops of Sir Henry Rawlinson’s 5th Army left their trenches and advanced on the German trenches across no-man’s-land. […]