Reading time: 8 minutes

Archaeology in the rugged landscape of Georgia reveals a medieval world where caves and underground shelters provided refuge from raiders, allowing a threatened civilisation to flourish

Southwest Georgia, close to the borders with Turkey and Armenia, is dotted with the remains of ancient defences.

Many of these structures – great and small, highly visible or hidden away – reflect the near-constant conflicts that shaped this frontier zone in medieval times.

By Abby Robinson, University of Melbourne

The country was the target of Arab and Byzantine forces, Turks, Mongols and Persians alike.

During an extensive archaeological survey of more than 1300 square kilometres of the Samtskhe-Javakheti region, I recorded dozens of these places with my collaborator, field archaeologist Giorgi Khaburzania from the National Agency for Cultural Heritage Preservation Georgia.

The first thing that strikes you here is the spectacular landscape – deep river valleys with steep walls leading up to hills and plateaus – and for every kind of terrain, there is a matching defence.

We explored castles in the gorges, manmade or modified caves in the valley walls and an unusual kind of underground shelter called darnebi in the highlands where farming communities lived, and still live today.

The food they produced was crucial to sustaining medieval Georgia, and these shelters appear to have provided them with important protection from raiders.

Together, these three defences made this borderland unconquerable. That the people survived and later thrived is borne out by Georgia’s eventual emergence as a medieval power.

And the caves and humble darnebi were just as crucial to this outcome as the grand castles.

INVULNERABLE CASTLES

In this region, three castles – Khertvisi, Tmogvi and Oloda, are spaced out along no more than 30 kilometres of the Kura River valley.

Another, Toloshi, sits in the Tashli-Kishla gorge just to the west.

Built on rocky outcrops and bounded by fast-flowing rivers, these castles were (and still are) difficult to reach, involving steep climbs and sometimes slippery and narrow paths, often from only one tenable direction.

In fact, Giorgi needed his mountaineering skills to reach the tower at Toloshi castle. High walls, strengthened with mortar, augmented these already-considerable natural defences.

For the medieval period of Georgian history, we have wonderfully evocative chronicles and folktales to supplement the information we can gather from the material remains. These texts enhance the sense of the castles’ invulnerability.

In one account, the fearsome Arab general known locally as Abu Kasim meets his match at Tmogvi castle in 914 CE:

“[He] ravaged Samtskhe and Javakheti, and besieged the fortress of Tmogvi. When he saw its strength and fortifications, he departed…”

The castles were protected still further by strategic views of the approaches along the valleys.

In short, they could see what was coming.

When we plotted their outlooks using mapping software ArcGIS, it became apparent that the castles were all working together to monitor the major routes.

The texts also help to date the castles – they are most often mentioned in connection with events of the 10th to 12th centuries. None have yet been excavated.

COMPLEX CAVES

In the walls of the region’s gorges are many manmade or remodeled caves, some of which are elaborate houses or even whole villages.

Most of them, though, seem to have had a religious purpose – they were Christian churches or monasteries, some modest, some monumental.

They found their apogee in the monastery cave complex at Vardzia, construction of which began under King Giorgi III, who reigned between 1156 and 1184, and was completed during the rule of his famous daughter and successor, Queen Tamar (1184–1213).

Vardzia is more than 500 metres wide and comprises hundreds of rooms.

Given the clear religious associations of the caves, why include them in a study of defences? Well, there are at least three reasons.

First, there is evidence in the chronicles. Vardzia was as much a bunker as a chapel when Queen Tamar summoned her troops, led by her husband David Soslani, to prepare for battle in 1204:

“They did not tarry but hastened to the church of the Most Holy Virgin at Vardzia. She wept as she committed David Soslani and his army to Our Lady of Vardzia, with the standard which had brought them good fortune; and she sent forth the army from Vardzia.”

Second, there is an inscription in one of the caves itself.

Its author took refuge there when his city was sacked by a force of Seljuk Turks commanded by Bars, a son of sultan Alp Aslan:

“I have been in terrible trouble… [Bars] came to Javakheti and threatened all Christians and especially Akhalkalaki, which he conquered taking all prisoners with him.”

Finally, sometimes there is defensive architecture in the caves like narrow entrance tunnels and heavy stone doors.

We were surprised to notice that the same features also occurred in the darnebi, although researchers had not linked them in the past.

The extraordinary rock-cut darnebi shelters are widespread and common in the highlands of Samtskhe-Javakheti but very rarely found elsewhere.

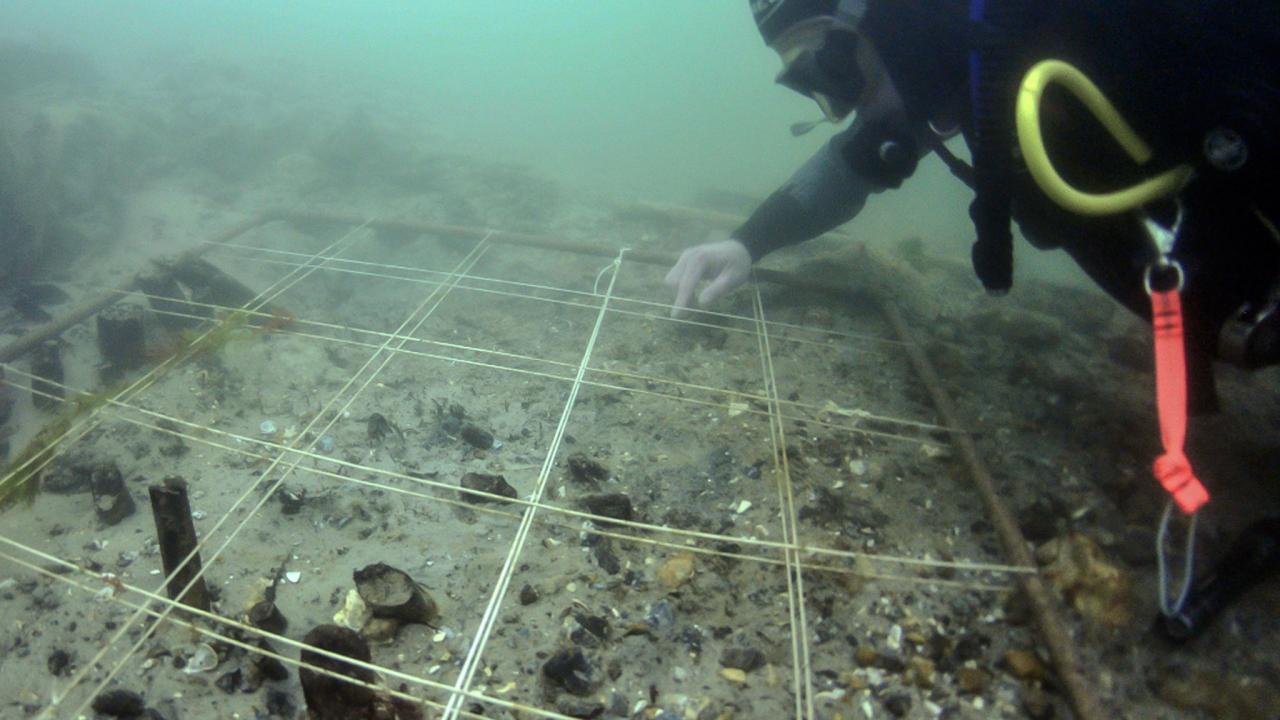

Only one of them has ever been excavated, by historian Dr Soso Burdiladze and archaeologist Dr Kakha Kakhiani in 2007.

Beneath the village of Lebisi, they uncovered an extensive system of tunnels and rooms.

Lamp niches and possible evidence of food preparation – a pit, smoke-blackened walls, a damaged millstone – complete a picture of a temporary underground home.

A heavy stone door, exactly like the ones we had encountered in the caves, closed the complex off to unwanted guests.

Crawling inside some of the unexcavated darnebi, Giorgi discovered that they all shared one or more features with Lebisi: entranceways and passages leading underground, tunnels, rooms and/or the distinctive stone doors.

There is evidence the caves and darnebi flourished alongside the castles in the 11th century.

If so, all three together formed a complete defence system, dispersed across the inhabited parts of Samtskhe-Javakheti and protecting every section of the population.

They would also have coincided with the rise of Georgia’s legendary King David IV, ‘the Builder’, who reigned between 1089 and 1125.

GEORGIA’S GOLDEN AGE

King David was the first of a line of monarchs, including his great-granddaughter Queen Tamar, to preside over what came to be known as the golden age of Georgia.

Once the southwest border was secured, the attention of these rulers could turn to expansion and growth. As a result, the Georgians were able, for a time, not only to hold their ground but expand their area of influence, ushering a period of thriving architecture, poetry and art.

Today, Georgia is on the verge of a second golden age, driven by international tourism and investment.

As development fast makes its mark on the historical borderlands of Samtskhe-Javakheti, urgent efforts are underway to have it included on UNESCO’s list of World Heritage sites.

The data we collected and the stories of the past it tells are now helping to make the case for the preservation of this unique part of Georgian culture.

This project is part of the Georgian-Australian Investigations in Archaeology (GAIA), a collaboration between the University of Melbourne and the Georgian National Museum. GAIA’s current focus is a field school for UoM undergraduates and a large-scale excavation at the important multi-period fortified site of Rabati, in Samtskhe-Javakheti. The directors are Associate Professor Andrew Jamieson, Dr Claudia Sagona from the University of Melbourne, and Dr Giorgi Bedianashvili from the Georgian National Museum.

This article was originally published in Pursuit. Read the original article.