Reading time: 7 minutes

Video games love historical settings: from adventure games like the Assassin’s Creed series, to action games like Call of Duty and its sequels, to strategic sagas like Europa Universalis; there’s no shortage of examples. Can computer games be more than entertainment, though, and can they actually teach their audience about what happened in the past?

By Fergus O’Sullivan

That can be pretty difficult to pin down, says Pieter Van den Heede, a lecturer at the Erasmus University in Rotterdam and author of Engaging with the Second World War through Digital Gaming, a thesis that looked at how games and their marketing materials can influence our view of the Second World War. On the one hand, he says during our interview, games can make a meaningful contribution to our insight into what history is.

Historical sediment

One good example he brings up is Sid Meier’s Civilization from 1991, where he could compare the different states of his in-game map and see how his actions, and that of his AI opponents, influenced how the world looked. For instance, he often changed the names of the cities he conquered, creating a constantly shifting pattern not unlike what we often have seen in Central European history. As a result, he says, he experienced “a historical insight I didn’t get elsewhere.”

According to Van den Heede, “to understand the history of a place, you need to understand the encounters that took place there,” he says. In his example, Civilization shows you how with every event, a “sediment” can form which can transform a place in significant ways. Like walking down the street in a place like Goa, India, yet still get a Portuguese feel.

The way games can choose to approach history, namely by letting players make decisions and then experience the consequences, can add a richness to the way we approach history. “It added a whole new dimension to my understanding of the past,” says Van den Heede. That said, there are limits to how games can impart history.

The way games are set up, they don’t primarily “teach” history, but rather represent it and they’re bound to make mistakes. To stick with the example of Civilization, by-and-large it only has one way to progress in technology regardless of which civilization you choose to play, and you plod through it in more or less the same order. You can also claim that the game is very Eurocentric, something it shares with most history-based strategy games, even more intricate titles like Europa Universalis.

A source like any other

Then again, any criticism you level at a game or film about the tone and setting you can also level at more serious scholarship. As Van den Heede says, anything you create is influenced by who you are and where you get your information. If you skip a source, knowingly or unknowingly you’re slanting the piece a certain way.

In his view, it’s important to get past the post-modern criticism and get people interested in the way we process history. The idea of constantly asking questions of the way history is pictured, thus making history a process of continued interrogation rather than something we consume. If you can somehow create venues where we consume media and then have a serious conversation about it, we have a powerful way to reflect on history.

Games are in Van den Heede’s view an excellent medium to get started with this process, especially since they’re very good at drawing you in emotionally and teaching you the “mechanics” of events; “this is what happens when a battle is won in a certain place.” That said, games are still primarily a medium of entertainment and as such distort history more than a good book does. They may set a train of thought in motion, but you need to keep fuelling the engine.

Finding depth

Much better would be if a game’s community, or even developers, would organise a chat talking about the history of a game. You could talk about what is missing from a game? Why did a game choose to take purely a military slant? What does it say about the narrative that’s created? Paradox Interactive does this with a package of history lessons that integrates with Europa Universalis IV, but are there further steps we can take?

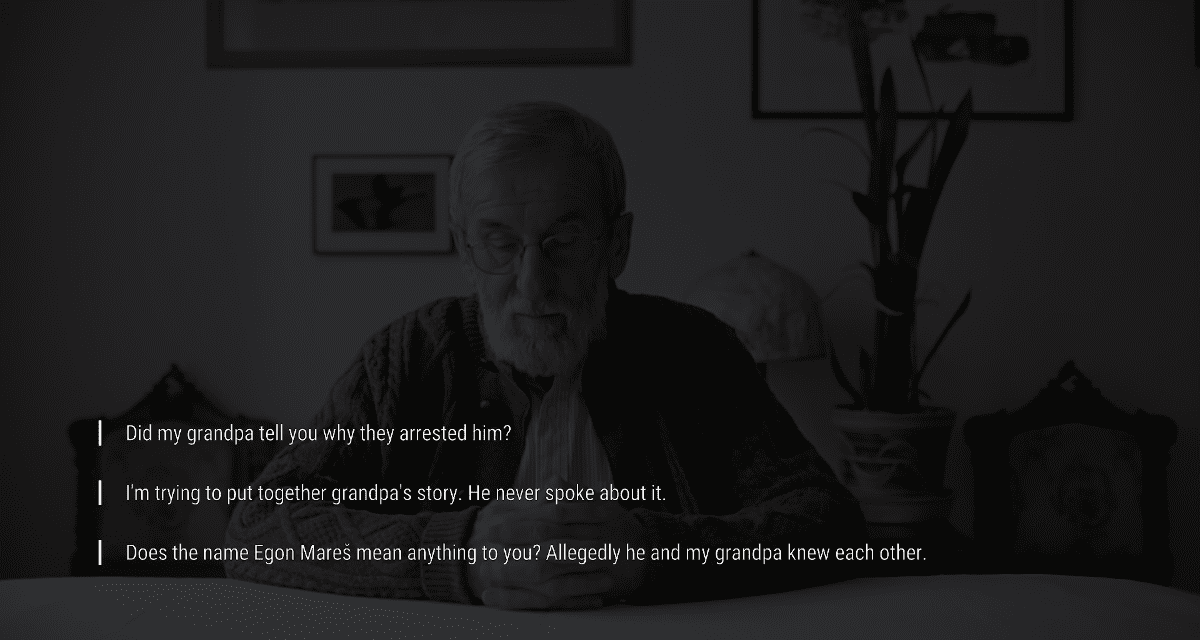

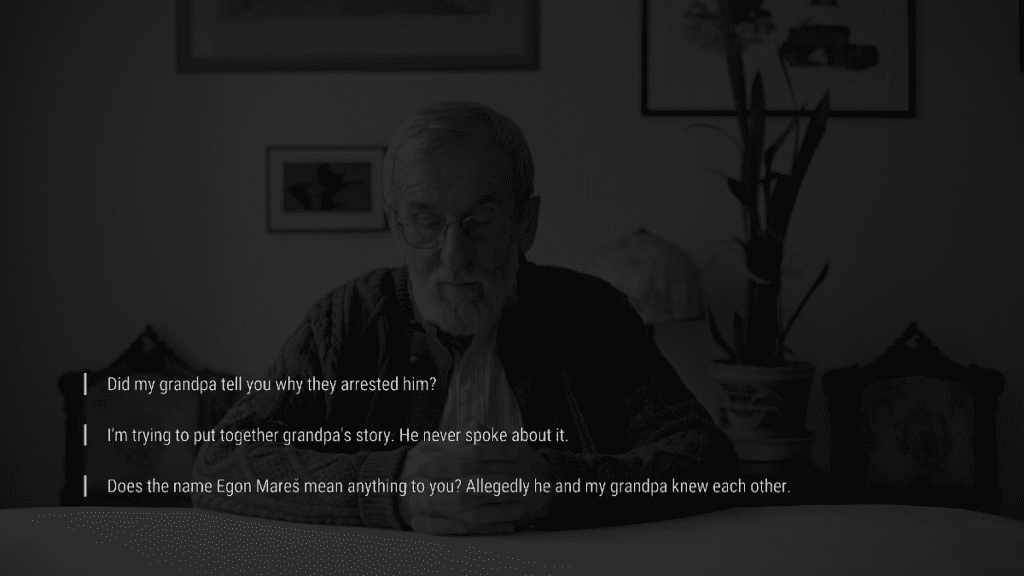

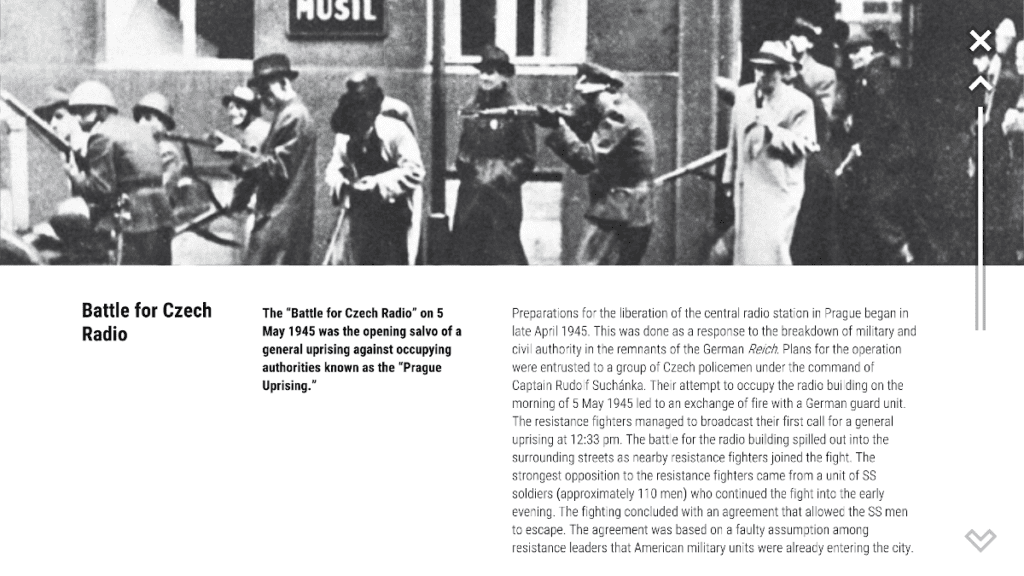

A great example of asking questions of history can be found in Attentat 1942, a Czech game that places you in the shoes of somebody interested in what happened to their grandfather, who was taken away by secret police right after the assassination of Heydrich, the German official in charge of occupied Czechia, in 1942. Was he involved somehow? Or was something else going on? You find out the answer by visiting people who knew your grandfather at the time, asking them what happened.

As Van den Heede remarks, a game like Attentat 1942 is far more interested in the methodology of history. If you ask the wrong question, an interviewee might throw you out of their apartment, but if you let them ramble too long you may never get the answer you need — experiences that any interviewer will tell you can really happen.

As a game that was at first developed for Czech classrooms, Attentat 1942. and its successor Svoboda 1945, were intended as a way to spark classroom discussion, with teachers given instructions on how to do so. As such, they meet a lot of Van den Heede’s criteria. However, as he himself admits, as fun as they are they’ll never get the same mass appeal that a heavily marketed shooter will have.

Outside of the narrative

From a historian’s perspective, commercial games often choose narrative impetus rather than contextualising history. As a result, players are learning something about what happened in the past, but may not always fully grasp what they’re experiencing. For example, in Call of Duty: WWII you walk through a liberated concentration camp for Jewish American POWs, but players aren’t left to dwell on what happened there. You walk through, and roll credits.

The scene in question.

A better example would be Brothers in Arms, a game that would give you a little more background on what your actions during the last level meant. According to Van den Heede, this gave players a lot of material to draw from if they ever decided to dig a little deeper into the history of the game.

As a medium, games are a great way for people to learn something new in a playful manner, and it seems a shame that they’re not used that way more often. It wouldn’t make games any less compelling; in fact, it could make them even better, says Van den Heede.

At the same time, there is a larger role set aside for historians, as well. Van den Heede suggests that we could, for example, confirm work on historical simulations as a serious work of scholarship. Historians could help model spread of disease, for example by looking at sources surrounding the Black Plague.

When you look at serious historical games like Attentat 1942, Through the Darkest of Times, or even wartime simulation game This War of Mine, there’s no doubt games have a role to play in historical education. It’s up to game developers, teachers, and academics to make this a reality.

Articles you may also like

Trump Administration’s Attempts to Curtail Academic Freedom

History Guild supports the Australian Historical Association’s Statement in Response to the Trump Administration’s Attempts to Curtail Academic Freedom. The Australian Historical Association stands in solidarity with our colleagues in the United States of America, where President Donald Trump is attempting far-reaching political interference in the work of historians and museum sector professionals. In his […]

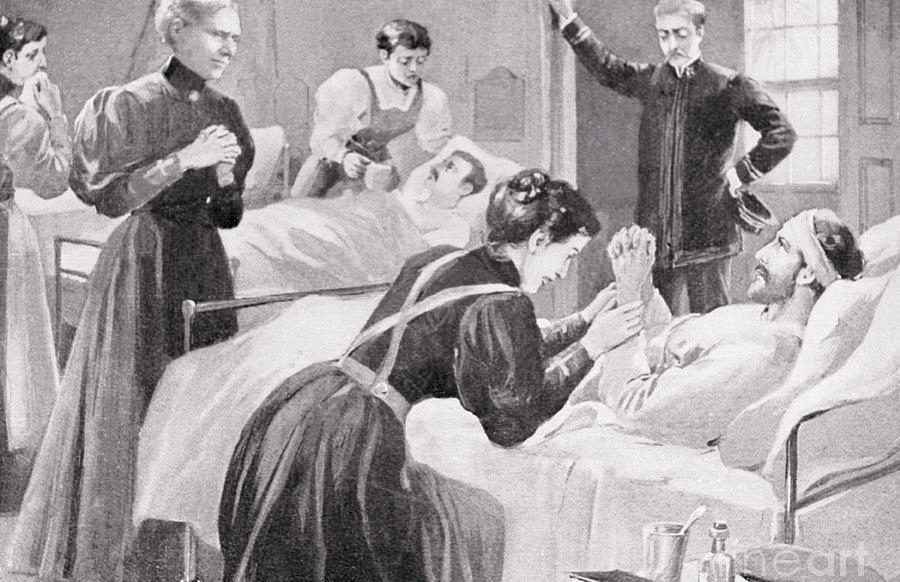

The Life of Clara Barton – Volume 2 – Audiobook

THE LIFE OF CLARA BARTON – VOLUME 2 – AUDIOBOOK By William E. Barton (1861 – 1930) Clarissa Harlowe Barton (December 25, 1821 – April 12, 1912) was a pioneering American nurse who founded the American Red Cross. She was a hospital nurse in the American Civil War, a teacher, and a patent clerk. Since nursing […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.