Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

The 200th anniversary of his death (1821-2021) renews discussion on how the former Emperor should be commemorated.

By Michael Vecchio

Military genius. Autocratic despot. Progressive visionary. Bloodthirsty war monger. The contrasting list of terms to describe the legacy of Napoleon Bonaparte indicate just how polarizing of a figure the former French Emperor was not only during his lifetime, but continuously into the modern era.

Now two centuries after his death on the island of Saint Helena on May 5, 1821, the utterance of the name Napoleon still brings up fervent discussion amongst historians and the public as to how this diminutive Corsican should be commemorated; yet whether one is for or against him the one word that would be on the list of both sides of the argument is surely, unforgettable.

In reality it is indeed possible to label certain historical individuals a hero and a villain, as contradictory as it may seem. The life of Napoleon Bonaparte is but one of the best examples of this; simultaneously uniting, inspiring, and building his nation in an age of constant war, the youthful brilliance and ambition of Napoleon would only be masked by a growing addiction to power and a seemingly endless quest for foreign dominance.

Born to Italian parents on the French controlled island of Corsica in 1769, Napoleon’s early life was a showcase of a budding prodigy; his rapid ascent in the French military entrenched his unmatched ambition making him one of Europe’s leading generals by his late twenties. Dashing, charming, motivated, and brilliant, the presence of Napoleon became a true representation of the future of France. Taking advantage of the unstable situation after its sanguineous Revolution, the young general had an ambitious agenda for himself and the country.

Though he would be subsequently criticized for betraying the principles of the Revolution, in effect becoming the undisputed Emperor of the French, Napoleon aimed to transform the nation through a new style of leadership and progressive vision.

While seemingly unchecked in his position of power, Emperor Napoleon incarnated the notion of an “Enlightened despot” establishing numerous liberal reforms throughout the French Empire. Amongst these actions included a road and sewer system, greater access to higher education, the famed Napoleonic Code of French Civil Law (still in place today, though with amendments), the creation of the Banque de France, the adoption of the metric system, the re-chartering of the Académie Francaise and the formation of the Legion D’honneur order of merit, amongst others.

He encouraged the flourishing of arts and science, religious tolerance, and secular education; and yet to achieve and promote these goals and solidify himself as ruler outside of France’s borders, Napoleon’s realm would find itself in continued conflict with much of Europe’s other powers. Whether it was the British, the Prussians, the Austrians, the Spanish, or the Russians, the list of France’s foes grew with every year of Napoleon’s rule.

Initially vastly successful with Napoleon’s military innovations (mobile artillery and such strategies like the Manoeuvre de Derriere), opponents eventually caught on to his style of warfare, and many adopted similar techniques against him. These series of conflicts which spanned his entire reign would be known as the Napoleonic Wars, and saw victories and defeats for the already controversial Emperor.

Though the quality of life had certainly improved for many in France itself, the cost of war and conquest marred Napoleon’s reputation; death, debt, and humiliation had reduced the glory of France and whatever progress his reforms initiated, while citizens of occupied countries had little access to the rights of the French.

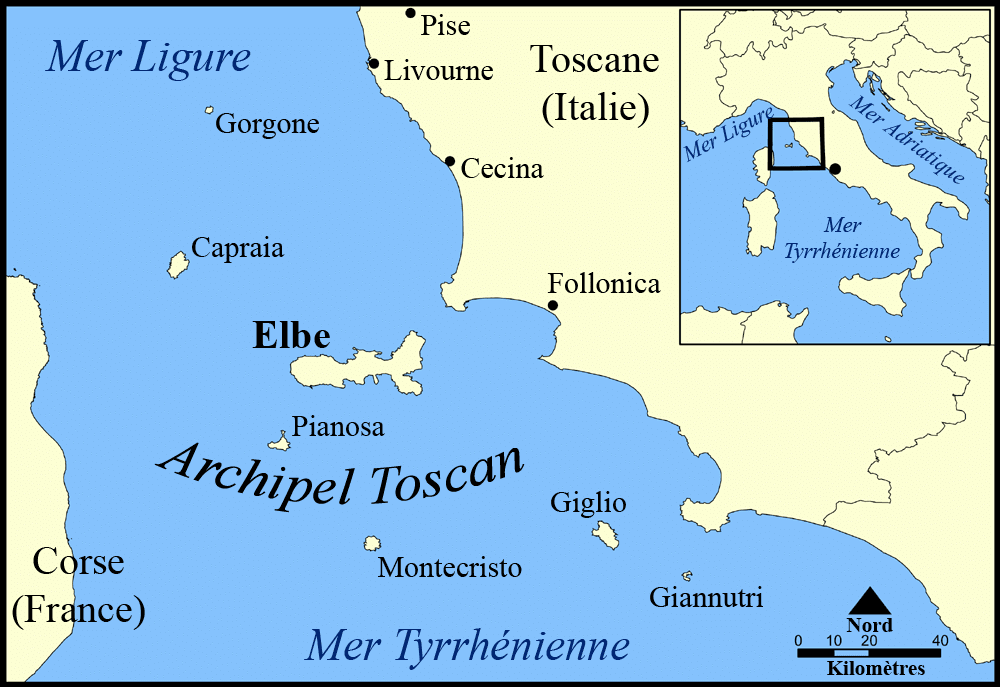

After a failed invasion of Russia in the summer of 1812, a coalition of Russian, Prussian and Austrian forces defeated Napoleon forcing his abdication and exile to the Mediterranean island of Elba in 1814.

It would be a brief departure, for the seemingly vanquished Emperor who had an amazing ability to rouse the emotions of his countrymen, escaped his exile and returned to Paris for a period now known as the Hundred Days, taking back control of the country he had ruled for a over decade.

Thus came the decisive Battle of Waterloo in June of 1815, where again the once mighty Napoleon was defeated, vanquished, and exiled for good. This time however his isolation would be on Saint Helena, a remote British island in the South Atlantic.

Upon his death in 1821, the 52-year-old Napoleon was immediately glorified, lauded, and of course vilified. 200 years later, his legacy remains as complex as ever; France and Europe were forever transformed by the Napoleonic era, and no single leader had a greater impact on the continent in the 19th century. While names like Garibaldi and Bismarck too would shape their nations, no man was so intrinsically tied to the destiny of his country for better or worse like Napoleon Bonaparte.

As historian David A. Bell notes in his book, Napoleon: A Concise Biography, “In France, the laws, and institutions he created still largely stand; much of central Paris still bears his mark, from the additions to the Louvre to the Arc de Triomphe. Film, television and literature have returned to him in regular intervals.” Still he remains a flawed, yet eternally fascinating figure of world history, who is embedded in popular culture and forever etched an image of the romantic and visionary leader. Bell concludes that;

“Napoleon may have been, from many points of view, a criminal, but he was not a criminal on the scale of the twentieth century dictators, who made mass murder and terror the basis of their social and political systems.”

David A. Bell.

For all of Napoleon’s errors and crimes, his life was also an embodiment of human ambition, possibility, and genius. And so while we may recoil in horror at parts of a legacy of war and conquest, we also stand back in awe at a visionary man that left an indelible imprint on the world, unlikely to be replicated.