Reading time: 13 minutes

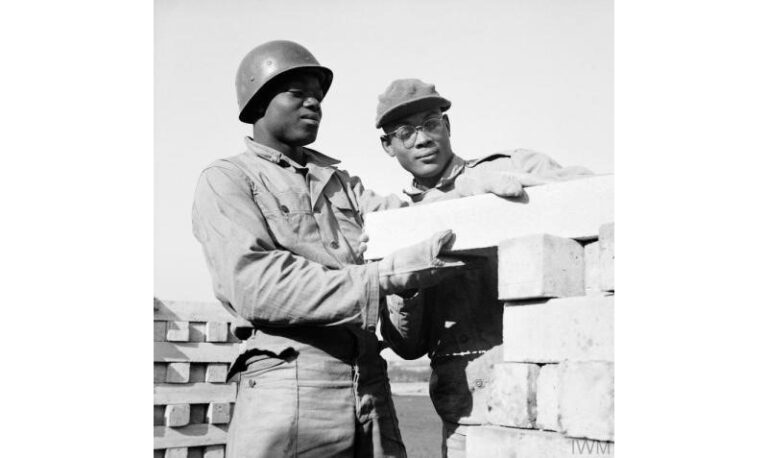

In this blog post I’m going to draw on the Cabinet Papers to explore the British Government’s response to the arrival of Black GIs in Britain during the Second World War. I refer to government records and other primary sources of the time which use terminology which we now consider offensive, for example, ‘coloured troops’ and ‘negroes’.

Several years ago I recall hearing a story about villagers in the West Country during the Second World War refusing to go along with a local US Army segregation order that Black GIs were excluded from the local pub and that only white American troops could use it – the villagers protested and effectively overturned this order. I’m pretty certain that it was the singer-songwriter and activist Billy Bragg that related this story to me, when I had the pleasure to meet him some years back. The story made a big impression on me and I thought, one day, I must follow this thread up. Now I have, and here are the fruits of my research so far.

By Mark Dunton

President Franklin Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill negotiated the decision to send US troops to Britain in late 1941. The first wave of (white) American troops arrived in the British Isles on 26 January 1942, at Belfast in Northern Ireland. The Britain of 1942 was not as ethnically diverse as Britain today.

When it became clear that a proportion of Black troops were going to be sent, one can see the British Government trying to ‘put the brakes on’, attempting to restrict the numbers. Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden was the leading advocate of this approach, as we can see from this extract from the Cabinet Minutes of 31 August 1942.

‘The Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs said that it seemed that the United States authorities were still sending over the full authorised proportion of coloured troops (about 10 per cent) with the contingents of forces reaching this country. Having regard to the various difficulties to which this policy was likely to give rise (including the fact that the health of coloured troops would be likely to suffer during the English winter), he thought that we were justified in pressing the United States authorities to reduce as far as possible the number of coloured troops included in the contingents of United States forces sent to this country.

This view was endorsed by the War Cabinet.’CAB 65/27/35, WM (42) 119

Eden’s argument that ‘the health of coloured troops would be likely to suffer during the English winter’, is, I have to say, fatuous. He clearly had no idea about Black communities routinely dealing with harsh winters in Detroit, Chicago and New York! What was really behind this strong desire to restrict the number of Black troops –what were ‘the various difficulties to which this policy was likely to give rise’?

The government was concerned about how the British people would react if white Americans tried to impose segregation (described as the ‘Jim Crow’ laws) in their villages and towns. They were worried that the public would object if it saw Black troops being treated unfairly; and they were also concerned that some white American soldiers might react aggressively if they saw the Black GIs being welcomed with kindness. And, as I will show in my second blog post on this subject, they were broadly right that the British public would be supportive of the Black GIs.

Another factor was that Britain was a colonial power and the issues surrounding the ‘colour problem’ could well have implications for Britain’s relations with its colonial allies, the peoples of the territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. British politicians were conscious of this and therefore reluctant to tell America what it should be doing, and they did not want to jeopardise relations with a crucial ally.

Confused approach

The British Government floundered around in its attempts to address the issues raised by US segregation policies. As author and journalist Linda Hervieux has written, ‘reluctance to tackle the issue directly by Churchill’s government would lead to much dithering over how to handle the matters raised by America’s race problem. The result would be confusion’.

In early August 1942 a British Army Officer, Major General Arthur Dowler, who was in charge of the administration of Southern Command, decided to issue some guidance on his own initiative entitled ‘Notes on relations with Coloured Troops’. The distribution was intended to be limited, but it was apparently widely circulated. This guidance became known as ‘Dowler’s Notes’. The key passage of this, expressing the most appalling and breathtaking prejudice, makes for a truly depressing read. It is also riddled with contradictions.

‘While there are many coloured men of high mentality and cultural distinction, the generality are of a simple mental outlook. They work hard when they have no money and when they have money prefer to do nothing until it is gone. In short they do not have the white man’s ability to think and act to a plan. Their spiritual outlook is well known and their songs give the clue to their nature. They respond to sympathetic treatment. They are natural psychologists in that they can size up a white man’s character and can take advantage of a weakness. Too much freedom, too wide associations with white men tend to make them lose their heads and have on occasions led to civil strife. This occurred after the last war due to too free treatment and associations which they had experienced in France.’CAB 66/29/21, WP (42) 44

Dowler went on to state: ‘White women should not associate with coloured men. It follows then, they should not walk out, dance or drink with them.’ Dowler’s guidance was tantamount to complicity with the segregation-style policies. By contrast, in early September 1942, F A Newsam of the Home Office issued this directive to chief constables across the country.

‘It is not the policy of His Majesty’s Government that any discrimination as regards the treatment of coloured troops should be made by the British authorities. The Secretary of State, therefore, would be glad if you would be good enough to take steps to ensure that the police do not make any approach to the proprietors of public houses, restaurants, cinemas or other places of entertainment with a view to discriminating against coloured troops.’CAB 66/29/36, WP (42) 456

There were significant differences between members of the Cabinet on this subject. The Minister of Information, Brendan Bracken, produced an article in the Sunday Express headlined ‘Colour Bar must go’. By contrast the Secretary of State for War, Sir James Grigg, issued a memorandum ‘suggesting that Army personnel should be educated to adopt towards coloured troops the attitude adopted by the United States Army authorities’.

Cabinet debate

The War Cabinet debated the subject at a meeting on 13 October 1942. The Cabinet minutes record that ‘it was generally agreed that the people of this country should avoid becoming too friendly with coloured American troops’. However, the discussion was more nuanced than this depressing statement would suggest. The Secretary of State for the Colonies ‘expressed some uneasiness’ about this point, though he was concerned with safeguarding the relationship with the colonies, rather being driven by a broader anti-racist or humanitarian sentiment.

‘The Secretary of State for the Colonies expressed some uneasiness at the point made under (2) above, namely, that the people of this country should avoid becoming too friendly with coloured American troops. He thought that this involved some departure from the attitude hitherto adopted towards coloured British subjects who came to this country, and that there was a risk of creating an atmosphere which would give offence to the coloured people now in this country and lead to their becoming a focus of discontent when they returned to their homes in the Colonies.’CAB 65/28/10, WM (42) 140

Another point was expressed during the discussion – that the Americans ‘must not expect our authorities, civil or military, to assist them in enforcing a policy of segregation’. And the suggestion was made that it would be desirable to refer in future to ‘American negroes’ rather than ‘United States coloured troops’. The reason for this change in terminology was not explained.

The dominant figure in this debate was Sir Stafford Cripps, the Lord Privy Seal. He was tasked by the Cabinet with drawing up a revised memorandum (‘United States Negro Troops in the United Kingdom’) which was to be circulated as ‘Private and Confidential’, for limited basis to senior officers in the Army and Royal Air Force. Looking at this document it is disappointing to find that Cripps, in his analysis of the situation in the USA, reflects some elements which appear in Dowler’s notes. One could argue that he is describing prejudicial attitudes rather than lending support to them, but again, to read this memo makes for uncomfortable reading:

‘In the South the white population still tend to regard Negroes as children for whom they have a moral responsibility; like children Negroes commonly inspire affection and admiration; but they are not considered “equal” to white men and women any more than children are considered equal to adults, although an increasing number of them are now playing an active and influential part in the public life of communities in which they live.’ CAB 66/30/3, WP (42) 473

Cripps went on to argue that ‘it is not for us to embarrass them [the Americans], even if we have different views on how race relationships should be treated in our own country and in the Empire … there is no reason why British soldiers and auxiliaries should adopt the American attitude but they should respect it and avoid making it a subject for argument and dispute’. His view on white women mixing with Black soldiers was slightly more nuanced than that advocated by Dowler: ‘for a white woman to go about in the company of a Negro American is likely to lead to controversy and ill-feeling, it may also be misunderstood by the Negro troops themselves. This does not mean that friendly hospitality in the home or in social gatherings need be ruled out, though in such cases care should be taken not to invite white and coloured American troops at the same time’.

So this memo represented the British Government’s advice on the subject. It was far from clear and open to interpretation. President Eisenhower took some enlightened measures but was not prepared to enforce racial integration in the US army. He left matters to the judgment of his local commanders. As Linda Hervieux has written, ‘the result was a series of orders by subordinates that wove a crazy quilt of Jim Crow across Britain’ (footnote 4). In my second blog post I will explore how this played out on the ground – and there were many heart-warming and refreshing aspects regarding the reaction of the British public to the presence of the Black GIs in Britain.

The first white American troops landed in Northern Ireland in January 1942, and they soon began to arrive in the rest of the UK. The friendliness, informality and cheerfulness of the GIs were greatly appreciated by the British public. It is well known that the GIs brought various treats to war-battered, heavily rationed Britain – including fruits, chocolate bars and chewing gum.

There were many positive interactions with the British public in general, many acts of kindness. My Mum has a childhood memory of being given an orange (a true rarity in war-torn Britain) by friendly GIs in Bridport (Dorset) and being allowed to take a ride in their jeep. The American Red Cross arranged dances and concerts, and local girls found themselves dancing the ‘jitterbug’ with these glamorous new arrivals in their smart uniforms.

The American presence was a huge boost to the morale of the British public, strengthening the conviction that the allies would be victorious. These were our allies, our friends, coming to fight alongside us. The strong appeal of this huge influx of American troops was captured in the uplifting music of Glen Miller, with its promise of a better world to come.

But there was a troubling undercurrent. The British people were taken aback by the prejudice directed at Black people by many white Americans. Author and journalist Linda Hervieux cites an incident in March 1942:

‘a group of U.S Marines outside a London restaurant accosted Samson Morris, a black corporal from the Caribbean serving with the British forces.

“You’re not going in there to eat with us”, a marine told Morris.

“I am a British subject from the West Indies and you are not in America where you lynch us people”, retorted Morris.

More marines entered the fray until there were six, and one grabbed Morris by the collar. A policeman intervened before the situation got out of hand’.From ‘Forgotten: The Untold Stories of D-Day’s Black Heroes’, Linda Hervieux (Amberley, 2019), p.167-68

This incident was discussed at a high level in Churchill’s government, but the Foreign Office decided not to take a forceful line about it when presenting a report about the incident to the US chargé d’affaires.

Signs of enlightenment

I previously explored the British Government’s response to the arrival of Black GIs in Britain during the Second World War. There were some depressing statements (not unsurprising) though the messages emanating from government were occasionally enlightened, for example, the Home Office directive of September 1942 which began ‘It is not the policy of His Majesty’s Government that any discrimination as regards the treatment of coloured troops should be made by the British authorities’. In this post I’m going to focus on the reaction of the British public to the African-American soldiers who came to this country to prepare for the grand invasions that were to take place in Europe.

The picture I’m going to paint has some refreshingly positive aspects reflecting opposition to racism but, of course, I’m not viewing the past with rose-tinted spectacles. The Sunday Pictorial quoted the views of a Somerset vicar’s wife: ‘If she [a white woman] is walking on the pavement and a coloured soldier is coming toward her, she crosses to another pavement … White women, of course, must have no relationship with coloured troops. On no account must coloured troops be invited into the homes of white women’.

However, the Sunday Pictorial countered this, in robust terms:

‘Any coloured soldier who reads this may rest assured that there is no colour bar in this country and that he is as welcome as any other Allied Soldier. He will find that the vast majority of people here have nothing but repugnance for the narrow-minded, uninformed prejudices expressed by the Vicar’s wife. There is – and will be – no persecution of coloured people in Britain’.

We have seen, in my first blog post, how racial prejudice could sometimes find confident expression which remains shocking to read, as in Major Dowler’s notes. However, as Kate Werran points out, Ministry of Information opinion surveys and other government analysis, censored letters, diaries, newspapers and articles all show, convincingly, that ‘Major Dowler’s unreconstructed view was not the majority opinion. At all’.

It is good to keep in mind the fact that ‘in most areas of the UK where black G.I.s were stationed, locals would have been seeing and interacting with black people for the first time’ (the Britain of 1942 was not as ethnically diverse as the Britain of today). There is a considerable amount of evidence showing that the British public were well-disposed to Black GIs, whereas reactions to their white comrades sometimes struck a critical note. The celebrated author and journalist George Orwell wrote that ‘the general consensus of opinion seems to be that the only American soldiers with decent manners are the Negroes’.

Black American soldiers welcomed

Weekly reports by the Home Intelligence Division of the Ministry of Information (MOI), based on surveys of public opinion, tend to support this view, for example, ‘the good behaviour and manners of the coloured troops is approved in three Regions’. A report by the Postal and Telegraph department of the MOI entitled ‘Opinion on American Troops in Britain’ of July 1943, quoted from a Hull canteen worker’s censored letter:

‘We find the coloured troops are much nicer to deal with … they’re always so courteous and have a very natural charm that most of the whites miss. Candidly, I’d far rather serve a regiment of the dusky lads than a couple of whites … All my friends – most of them were colour conscious before – who serve in canteens feel the same.’Catalogue ref: FO 371/34126

Her language jars with us today but her positive sentiments are certainly clear.

A report by the Home Intelligence Division of the MOI of 14 January 1943 stated that:

‘Discrimination against their coloured brethren by white U.S. soldiers has been criticised consistently though not on a very wide scale. The “colour bar” is criticised as being undemocratic and as “conflicting with the Englishman’s idea of fair play”.

Members of the public who witnessed discrimination being inflicted on Black servicemen appealed to the Government to intervene. Mark Mendoza, from Westcliff-on-Sea, wrote to the Foreign Secretary (Anthony Eden) on 25 May 1944. Mr Mendoza had taken his wife and two daughters to a dance at the Palace Hotel, Southend-on-Sea, where a group of over 100 US sailors and officers were present, including two ‘coloured’ sailors. Mr Mendoza described an ugly incident:

‘At about 9 o’clock five or six white sailors attacked one of the coloured men simply because he was dancing with a white girl. American Officers … ordered the victim out of the place and in spite of protests from several of the British people who were incensed at this absurd behaviour, he was forcibly ejected. An ugly scene seemed to be presenting itself as the ladies then refused to dance with the Americans who began to show their annoyance and feeling rang so high that the management stopped the dance.’Catalogue ref: FO 371/38624

Mr Mendoza conveyed his outrage to the Foreign Secretary in eloquent terms:

‘I am particularly disgusted that at this point of the War when so many men are dying in the fight for the rights of mankind, this sort of persecution should be allowed a free hand in our liberty loving Empire.’

He goes on to mention other examples of racial prejudice when black soldiers had been victimised in Westcliff-on-Sea.

Mendoza’s reference to the Empire grates with our modern day sensibilities, but it needs to be viewed in the context of the time and there is no denying his total revulsion of witnessing prejudice in action.

Mr Mendoza received a brief reply from Nevile Butler of the Foreign Office, on behalf of Eden, dated 6 June 1944:

‘Mr Eden is grateful for the trouble you have taken in writing to him and he has noted your views. Every effort is naturally made by senior American officers in this country to guard against the occurrence of incidents of the sort you describe.’

I doubt that Mark Mendoza found this reply satisfactory.

Nuances to the historical story

Racial tensions within US military units repeatedly surfaced from 1942 until the close of the war. A particularly shocking incident took place on 26 September 1943, when there was a shootout between white and Black US servicemen in the Cornish town of Launceston, researched by Kate Werran.

However, it’s important to make the point that there were of course nuances to this historical story. Linda Hervieux makes the point that racial integration within the US army could, and sometimes did, occur: ‘A white soldier from Georgia stationed in central England found that he preferred the “Negro” Red Cross club to white clubs elsewhere. There, he was free to speak with black GIs, some of whom he befriended, something he would never have done in front of his white friends.’

As I hope I’ve demonstrated, there were many positive aspects to the stories concerning the African-American soldiers stationed in Britain, particularly the respect with which they were treated by many ordinary British people, who protested, and sometimes directly intervened, to stop the implementation of Jim Crow-style segregation. The Black GIs experienced a freedom and respect that they had not experienced at home, and they retained positive memories when they returned to the United States, which fed into the civil rights movement.

Further sources of interest

- Home Intelligence Reports can be searched on the MOI Digital website: Reports (moidigital.ac.uk)

- See also this excellent blog post, by Lucy Bland and Chamion Caballero, which includes some very interesting and moving stories: ‘Brown Babies’: The children born to black GI and white British women during the Second World War

This article was originally published in The National Archives.

Podcasts about African-American GIs in WW2

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 193

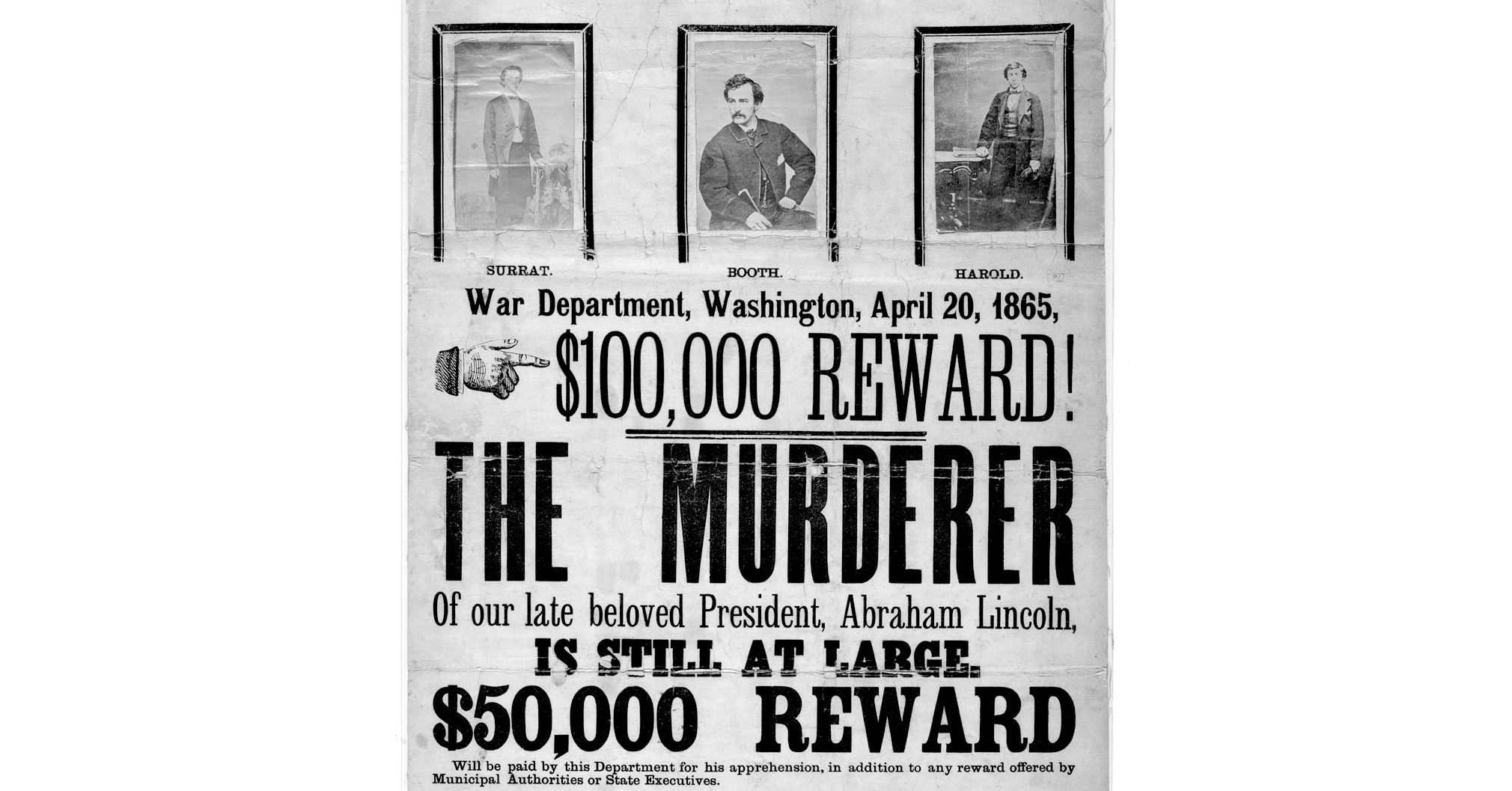

1. Who took over as US President after Abraham Lincoln was assassinated?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

Earning the Enemy’s Respect: Victoria Cross Recommendations from the Other Side

Reading time: 7 minutes

Many readers will be familiar with the 1964 epic movie Zulu, which depicts the 1879 landmark Battle of Rorke’s Drift in the Anglo-Zulu War. In the film, perhaps the most iconic scene takes place at the end of the movie, whereby the Zulu warriors chant in respectful salutation towards the British soldiers before withdrawing after the battle. Moving, cinematic, and honourable, it’s clear why the scene lives so memorably in the hearts of fans today.

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.