B.C. FRANKLIN AND THE TULSA MASSACRE

Reading time: 5 minutes

On May 31, 1921, Buck Colbert Franklin peered up at the Tulsa, Oklahoma, sky and saw planes dropping turpentine bombs onto the roofs of nearby homes and businesses. On the street around him, he watched Black women, men, and children being felled by the guns of their white neighbours. Under the guise of extracting retribution for a Black teenager’s supposed assault on a white woman a day before, white Tulsans strategically destroyed the physical manifestations of their Black neighbours’ success.

By Alaina E. Roberts

Franklin’s account of the Tulsa Massacre is now famous, after being rediscovered through the event’s depiction in HBO’s Watchmen and Lovecraft Country. These shows used the massacre to draw a parallel between racial violence of the past and present. With the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Massacre this year, a look at Franklin’s life offers a way into thinking and teaching about this event.

The father of famed historian and former AHA president John Hope Franklin, Buck Colbert Franklin, better known as B.C., was more than a bystander to the Tulsa Massacre. Rather, Franklin’s life is a testament to the triracial history of the region and representative of how integrating Black and Native history often provides a richer, broader historical narrative.

The son of a mother of mixed Choctaw and Black ancestry and a Black father who witnessed his own father buy his freedom from his Chickasaw enslaver, Franklin inhabited a world of intertwined Black and Native history from birth. The family’s upward mobility was made possible due to his father’s ability to settle on Indian land. Franklin embodied the prosperity that made Tulsa’s Black community so notable and the deeper Black-Native history that made it possible.

The western landscape where he grew up accommodated a spectrum of freedoms for Black people. Indian Territory (part of modern-day Oklahoma) was a space of enslavement from the time that the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creek, Choctaw, and Seminole Nations arrived with Black women and men in bondage, after being forcibly displaced from their southeastern homelands in the late 1820s and early 1830s. After the Civil War, treaties between the United States and these five nations forced them to emancipate, enfranchise, and provide land to people they had formerly enslaved. Thereafter, the Black and mixed-race people whose lives and legacies were linked to these Native polities lived a life unthinkable for most other newly freed people of African descent.

Many Black people chose to stay in Indian Territory, living relatively undisturbed on parcels of land communally owned by their tribes, building institutions, and voting and serving on juries. With the help of relatives, Franklin’s father accumulated hundreds of head of livestock and cultivated over 200 acres of land. After the passages of the Dawes Act (1887) and the Curtis Act (1898), legislation designed to break up and allot communally owned Indian land, Franklin and other Black people who lived in these Indian nations were able to obtain official ownership of land allotments promised to them in the post–Civil War treaties, providing them with a key to generational wealth and self-sufficiency.

This is a post–Civil War narrative different from that of the American South. When we teach this era, we should, of course, teach about African Americans’ fight to emancipate themselves and seek political rights, the Reconstruction Amendments, white violence, and lost opportunities to rebuild the United States as an equitable society.

But we should also teach about how the federal government used its power to secure land for Black people—not in the South, but in the West. Black landownership existed in the South, of course, but as I discuss in my book, I’ve Been Here All the While: Black Freedom on Native Land, in Indian Territory, the drive for western expansion joined with Republican goals for Black economic self-determination; in this time and space, opportunity for Black people was prized over tribal sovereignty, with Black landownership emerging from Native dispossession.

It was this confluence of circumstances, along with Franklin’s own intelligence and resilience, that enabled him to become a lawyer who read Latin and practiced among other Black attorneys. Franklin became known among Black people in Indian Territory for representing their interests in land and citizenship claims, among other legal issues.

This confluence also brought thousands of African Americans from the South to Indian Territory, seeking the rights, landownership, and prosperity that Black newspapers and information networks told them the former slaves of Indians enjoyed. They built all-Black towns and Black neighborhoods within cities like Tulsa. One such neighborhood was the Greenwood District, which would come to be known as “Black Wall Street” due to the success of its businesses and the affluence of its residents. This district would be almost entirely destroyed in the Tulsa Massacre.

Franklin arrived in Tulsa about four months before the massacre. In the aftermath of the event, which he termed a “holocaust,” he was part of a legal team that successfully argued against a new city ordinance requiring new buildings in the area to be fireproof; this would have significantly increased the cost of rebuilding, pricing out many business owners who had just suffered losses their insurance companies refused to cover.

Franklin’s life encapsulates the southeastern Indian settlement of Oklahoma, the white American intervention that accorded Black and Black-Native people rare land allotments, and the Black entrepreneurial success that made Black Wall Street the envy of African Americans around the country and the bane of its white neighbors.

With this heritage, his son John Hope Franklin built a career for himself as one of the most renowned historians of the Black experience. Both Franklins stand as examples of the importance of recognizing this Black-Native history as a unique but crucial facet of the Black American narrative.

This article was originally published in Perspectives on History.

Articles you may also be interested in

Reckoning with slavery: What a revolt’s archives tell us about who owns the past

Reading time: 6 minutes

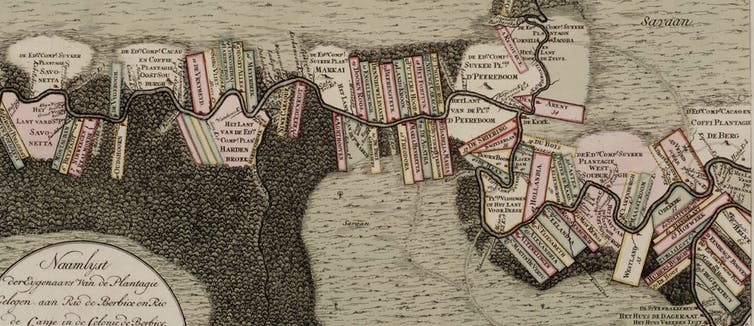

During the revolt, former slaves organized a government and controlled most of the colony for almost a year. The Dutch either fled altogether or holed up on a well-fortified sugar plantation near the coast. A regiment of European soldiers sent from neighboring Suriname mutinied and joined the rebels they had come to defeat. But obligated by treaties, indigenous peoples such as Carib and Arawak fought on the side of the Dutch. The revolt ended when the rebels, out of food and arms, were overpowered by enemies who had received an infusion of men and supplies from the Dutch Republic.

The text of this article is republished from Perspectives on History under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.