Reading time: 11 minutes

The Siege of Malta, a two-year ordeal of bombs, heat and dust, was one of the most important battles of the Mediterranean theatre in World War Two. Few of the victories in North Africa and Italy would have been possible had the island fallen to the Axis. In this article, we let Australian pilots who defended Malta tell their stories.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

This article is part of our series about Australians in the Mediterranean in World War Two and draws heavily on the Australians at War Film Archive. We have a similar article about Australian experiences during the Siege of Malta on the site, as well.

Malta and control over the Med

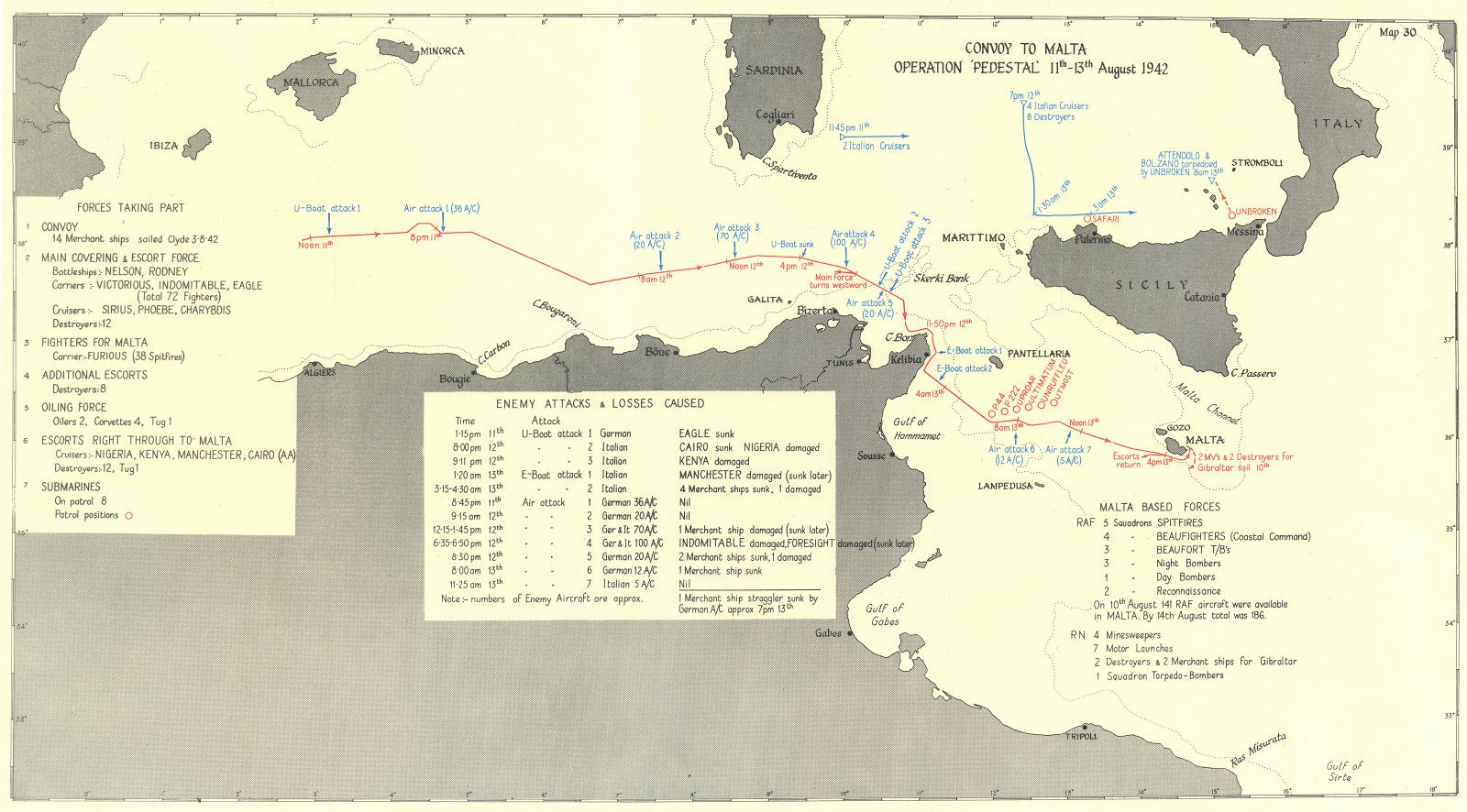

The island of Malta is situated at almost the dead center of the Mediterranean, giving the Royal Navy a perfect port to resupply their ships and the Royal Air Force a base to conduct raids against targets all over Italy, Sicily, Tunisia, and Libya. The air and sea support Allied troops needed during events like the Benghazi handicap would likely have been impossible without Malta.

The Axis, unsurprisingly, made Malta a prime target, with almost daily raids from mid-1940 until late 1942. At first, there wasn’t much the RAF could do about it. All they had was some ancient Gloster Gladiator biplanes which managed to shoot down one enemy bomber (we tell this story in our article on Australians in the fight for Malta’s survival) but were otherwise ineffectual.

An inauspicious start

In April 1941, as the North African campaign heated up, things started looking up for Malta’s defenders with the arrival of more advanced aircraft. George Paliser from Yorkshire, who moved to Australia after the war, remembers being part of the first wave to bolster Malta’s defences.

Mr. Paliser was part of the 249 squadron which after acquitting itself well in the Battle of Britain was to be sent to Cairo and fight the Italians in the desert. A flotilla including aircraft carriers was loaded up with modern Hurricane aircraft and set sail for the Middle East. However, for reasons unknown to Mr. Paliser, a brief stopover in Malta became a permanent posting — the brand-new Hurricanes, to his surprise, continued their journey.

This left Mr. Paliser and the rest of his squadron to fly the older planes at the airfield. He recalls taking the bus to the Tak Ali airfield in the north of the island and seeing the old biplanes. “I think one or two of them you could turn the prop with your hand you know, they were so crapped out. They were absolutely at the end of their tether.”

They quickly found out why the existing materiel was in such bad shape, as within a few days a raid destroyed almost all planes while they were still on the ground. According to Mr. Paliser, only about three planes were still airworthy; in fact, most losses in Malta were due to them getting shot up on the ground, which is confirmed by several other veterans interviewed.

Getting up and away

The Tak Ali airfield may have been under constant attack, at least there was a proper runway. The other, main airfield at Luqa, in the center of the island and now the site of the island’s international airport was a different story. In the words of Robert Cock from Adelaide, “to get off Luqa was a bit of a struggle.”

This is an understatement on the part of Mr. Cock. In his interview, Clarence Singe from Maryborough, Victoria, explains it in detail. “At the end of the airstrip was a great big area […] it was a quarry. It was a short runway, and if you hadn’t made your take off at the end of the quarry, you were curtains. So a few of us got together and decided we would make a ramp, the full width of the airstrip.”

Making the ramp was quite the undertaking, involving not just pilots and ground crew, but also engineering officers. Without heavy equipment, they needed to compact it by hand, then take a test flight, then see what could be improved. In Mr. Singe’s words, “we worked it out. Very gradual strip. Because when an aircraft hits it at a hundred and ten miles an hour, it makes a lot of difference. But the pilots liked it, they thought it was good.”

Bigger and better guns

What also improved were the planes. Where the biplanes couldn’t keep up with anything the Axis were throwing at Malta, soon the pilots were reinforced with much better aircraft. Robert Cowper from Broken Hill, NSW, tells the story of flying some of the first Beaufighters assigned to Malta.

Mr. Cowper, even sixty years after the war, clearly still loves the Beaufighter. “I’m indebted to the Beaufighter,” He says in his interview, then continues:

I would be dead now if it wasn’t for the Beaufighter because the Beaufighter saved my life. […] The Beaufighter was a good tough aircraft. It was really nice. You sat up the front, the pilot sat up the front in a little office of your own and you had good visibility, and they were tough and the engines were much more reliable in many ways than the Rolls Royce engine [from earlier aircraft]. The Rolls Royce engine had a radiator and a coolant and they were cooled like a car like, and if your radiator sprung a leak or you lost your coolant level, the engine seized up.

Squadron Leader Robert Cowper

The Beaufighter didn’t just perform better, it also had more and better guns than anything then on Malta. It boasted four cannon (which fire explosive shells) and six machine guns (which fire armour piercing, incendiary or tracer rounds) it was a massive upgrade to anything flying out of Malta before.

These cannon made all the difference, allowing the RAF to shoot even well armoured aircraft out of the sky. Mr. Paliser tells a story about going after a recon plane that was scouting the aircraft carrier in the Malta harbor. “our chaps had had a go at it […] but they found that the Germans had armour plating in a v-shaped thing over the back of the engine so when you attacked it from either side the bullets were just bouncing off this armour plate.”

In a meeting, Mr. Paliser and his squadron commander suggested that a Hurricane fighter, which normally only carried machine guns, be outfitted with cannons. Mr. Paliser was then volunteered to fly it: “My first four rounds — I think I’d only pressed the trigger for about two seconds — I’d knocked the engine out of the aircraft.”

Cannon weren’t just effective against aircraft, either: Mr. Paliser recalls a story where another, unnamed, pilot sunk an Italian destroyer using cannon fire. Though it took three passes, eventually the pilot managed to knock out the ship’s engine.

Air operations from Malta

Operations like this were part and parcel for the pilots on Malta. They often fly multiple missions per day, with the area they were flying changing as the fighting across the Mediterranean shifted. The only constant was the sorties flown against the bombing raids, which we talk about in our article Southern Cross over Malta.

However, there were plenty of opportunities to make use of Malta’s excellent location. In the early days of the siege, many of the missions flown by the interviewees were in aid of the forces fighting in Libya and Tunisia.

Kenneth Baird from Ballarat, Victoria recalls bombing Benghazi and Tunis: “Benghazi was search lights everywhere. We weren’t given oxygen on our aircraft in Malta because it was considered you didn’t have to go high enough to need it, but we went as high as we possibly could on circuits like that […] of course you’d puff and pant a bit, but it was better than going in lower and getting shot up more.”

Torpedoes away

Malta was a prime position from which to harass the Axis supply lines. Mr. Singe tells how more and more planes were fitted with torpedoes and depth charges, and how tricky it was to launch those properly as pilots had to fly in low and turn on a small search light (Mr Singe calls it a lee-light).

Once you turned your light on, they knew where you were. If you didn’t let your torpedoes and depth charges go pretty smartly and pull your lee-light up, you were in trouble. Once the two torpedoes went, your aircraft would go straight up in the air about five hundred feet. Straight up like that. You then turned either right or left, depending on what the strike was like, to avoid the explosion yourself, because you were so low. It was dangerous work.

Keith Cousins from Naranderra, NSW, confirms that dropping a torpedo was a precise science, saying you had to drop low to the target from “half a mile or less. Because once they hit water the little prop on the front would unwind and it was immediately armed. So yes the closer the better.”

That said, Mr. Cousins downplays the risk a little: ” if you’re down low you’ve got to remember that the ship can’t always depress its gun down if you’re down really low. A big ship. A small ship yes, they’d have a better chance I suppose of hitting you. But yes the ship we attacked we were in and gone before they were aware of it no doubt. Because nothing was fired at us.”

Raiding Italy

As the war progressed, the pilots would more and more conduct operations on Sicily and the Italian mainland, a hop, skip and a jump away. The enemy was so close, in fact, that Mr. Cowper tells about how at one time he and his squadron got lost flying at night and were worried about overshooting Malta and landing in Italy or Sicily instead. Mr. Singe even claims that Italy was so close they could hear enemy planes take off on a quiet night.

As a result, all interviewed pilots have some story about raiding Italy. There is some variation about how heavy the fighting was, with Mr. Baird attacking targets that were practically undefended, while Mr. Cowper tells a very different story: “[when] the raids on Sicily began we got fairly busy.”

During one raid on a railway emplacement, Mr. Cowper’s squadron of Beaufighters came under attack. He let the screening fighters handle it and says “I just got my usual distance away from them that I thought was quite safe and then we, the first couple of cannon shells that hit it set off a bomb or a mine and the most ginormous explosion […] and everything just disappeared in a cloud of dust and bits and pieces flew back and knocked the windscreen […] and my engine started running rough and there were holes everywhere. Bits of molten metal in my legs […] and I found the aircraft wouldn’t respond to the controls.”

The unlucky hit on his ordnance wasn’t the end for Mr. Cowper. As his plane went into a spin, he managed to pull the lever that would allow him to bail out of the aircraft. However, the constant spinning made him black out. He came to as he was falling through the air, with his plane dropping into the Mediterranean just a short distance away.

Mr. Cowper had the presence of mind to deploy his parachute, and he dropped not too far from a hospital ship which picked him up. No wonder, then, that he credits the Beaufighter with saving his life — without the bail-out mechanism working perfectly, it’s not likely that he would have survived.

Linchpin Malta

Malta played an outsized part in winning the war in North Africa and, later, the invasion of Sicily and Italy. It wasn’t until the war drew to a close and forces converged on central Europe that the tiny island, and the Australians who defended it, diminished in importance.

If you’d like to read more Australian accounts of the war, check out our other articles in this series, like the battle for Crete. If you’d like to visit Malta yourself and see where the fighting took place, we have a guide on exploring Malta.

Podcasts about Australians in the Mediterranean during WWII

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 171

1. When was the US White House burned by British forces?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The Battle of Long Tan – A Close Run Thing

Reading time: 11 minutes

The Battle of Long Tan, fought on August 18th, 1966, is a key battle in Australian military history, and the reason 18th August is designated as Australia’s official Vietnam Veterans’ Day. It was an early defining engagement for the 1st Australian Task Force (1 ATF) during their deployment in Vietnam, where the 108 men of D company, 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR), encountered a vastly superior Viet Cong (VC) force. The battle took place in a rubber plantation near the village of Long Tan in Phuoc Tuy Province, an area where Australia had been assigned responsibility for security.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.