Reading time: 7 minutes

The world loves a good April Fools’ Day prank – from telling your schoolmates it’s non-uniform to assuring a coworker the boss has definitely given everyone the day off, April 1st is a day of big and small pranks all around the world.

While mostly celebrated in Western countries such as Northern Europe, America, and other English-speaking countries like the UK, Australia, and New Zealand, much of the world knows of and sometimes takes part in the light-hearted tradition of April Fools.

But where does it come from?

The truth is, no one knows for sure.

A day of playing practical jokes, spreading hoaxes, and generally messing with your friends and family for fun, the history of April Fools Day is uncertain. Here’s what we do know about April Fools Day, along with some of the best pranks ever pulled.

When Did April Fools’ Day Start?

There are many historical origins for April Fools Day, although they almost all originate in Europe. One of the leading explanations comes from France in the 16th Century. Aiming to counter and respond to the rising protestant movement in Europe, Pope Gregory XIII called the Council of Trent which convened between 1545 and 1563, setting out to unify Catholic doctrine.

Within this came the idea of the Gregorian calendar, which Europe’s astronomers recommended to the Pope to fix the Julian calendar which lost 12 minutes every year. Soon after in 1582, King Charles IX of France reformed the calendar in line with most other Catholic nations in Europe. This had the effect of moving the start of the year from April 1st to January 1st.

Not everyone got the memo, and people who mistakenly continued to celebrate the new year in April were mockingly called “April fish” (poisson d’avril) and became the targets of pranks and hoaxes, starting with the placing of paper fish on a victim’s back. The term “April fish” persists in French-speaking areas, and likely comes from the abundance of fish in streams during early April, making them easy to catch – much like gullible people being pranked.

While the Gregorian calendar change is one of the leading historical explanations, some historians have also connected the modern April Fools’ Day to the ancient Roman festival of Hilaria, celebrated at the end of March. Like our current April Fools’ Day, during Hilaria Romans would dress up in disguises and mock fellow citizens and even magistrates. Given the timing and jovial nature of the festival, it may be related to modern April Fools – though no certain link has been established.

Similarly, some historians also link April Fools Day to the vernal equinox, which occurs in late March. This is because of Mother Nature “fooling” people with unpredictable weather during this time of year, as spring can bring both warm sunshine and unexpected snowfall. Historically speaking, the calendar change may seem the most plausible, however, our modern April Fools’ Day has likely been influenced by these other traditions as well.

How Did April Fools’ Day Become So Popular?

While it may have begun in the 1500s or even earlier, April Fools’ Day really became popular in the 18th Century in Britain – roughly around the time Britain also adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1752. Despite this, the earliest known April Fool’s Day prank in Britain occurred a little earlier, in 1698 – a prank we will get to later.

As Britain spread its influence and customs across the globe, April Fools’ Day went with it – and only continued to grow with its prominence in America and its rising global influence. In the 20th century, mass media gave a platform to corporate involvement in the day, massively boosting its popularity. Companies began to see the marketing potential in pulling elaborate pranks, often garnering widespread attention and free publicity. These corporate jokes, combined with media outlets joining in on the fun, helped solidify April Fools’ Day as a globally recognized phenomenon.

April Fools’ Day Around the World

While April Fools’ Day is mostly celebrated in Europe and English-speaking countries, similar traditions exist in other cultures. In Iran, the holiday of Dorugh-e Sizdah (literally “the lie of the 13th”) is celebrated on the 13th day of the Persian New Year, which usually falls on April 1st or 2nd. On this day, people play jokes on one another and enjoy outdoor picnics.

In Spanish-speaking countries, the Día de los Santos Inocentes (Day of the Holy Innocents) is celebrated on December 28th. While originally a solemn remembrance of King Herod’s massacre of young male children, it has evolved into a day of pranks and practical jokes similar to April Fools’ Day.

The Biggest and Greatest April Fools’ Day Pranks Ever Carried Out

Over the centuries, numerous memorable pranks have been pulled on April Fools’ Day. Here are five of the most famous and creative hoaxes:

Washing Lions in London

One of the earliest recorded April Fools’ Day pranks occurred in 1698 when several people in London were tricked into going to the Tower of London to ‘see the Lions washed.’ Pranksters distributed tickets for this non-existent event, and many Londoners turned up to nothing but other victims wandering around.

The prank was so successful that it would be repeated multiple times for a few hundred years after, with one victim of the 1848 prank stating:

‘I was not prepared for the extraordinary credulity of the British Public. They flocked up in shoals to see the lions washed. The warders were almost at their wits’ end. They had the bits of pasteboard flourished in their faces, with angry gestures and angrier imprecations, by the indignant crowd of sight-seers and seekers.‘

A Fake Eruption at Mount Edgecumbe Volcano

When you live next to a volcano, the last thing you want to see in the morning is unexpected smoke. In 1974, that’s exactly what the residents of Sitka, Alaska, woke up to. Smoke appeared to be pouring out of the nearby dormant Mount Edgecumbe volcano. Panic quickly spread across the town and soon made local and even national news – until a Coast Guard pilot investigated and discovered the truth.

Inside the volcano was a pile of old tyres, set alight by local prankster Oliver “Porky” Bickar, who had flown hundreds of old tyres into the volcano’s crater and set them on fire, along with spelling out ‘APRIL FOOL’ in 50-foot letters.

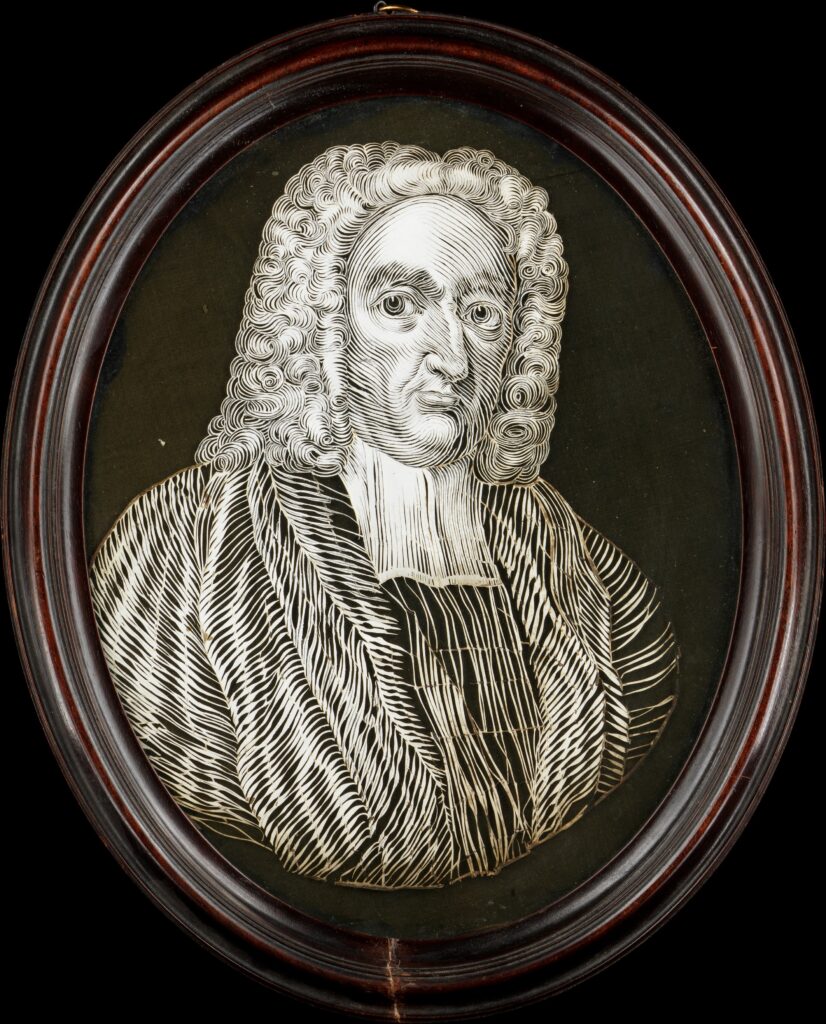

The Death of John Partridge

Going back to Britain and back in time to 1708, infamous satirist and writer Jonathan Swift set out to create one of the most targeted, elaborate, and long-running pranks in history. Adopting the pseudonym Isaac Bickerstaff, Jonathan Swift predicted the death of astrologer John Partridge, mocking Partridge’s own regular “predictions”.

Swift published an almanac forecasting Partridge’s death on March 29th, 1708. To further prepare his April Fools Day prank, he released an elegy confirming the astrologer’s demise on March 30th. Partridge, very much alive, was then forced to spend considerable effort convincing people he wasn’t dead on April 1st.

When Partridge eventually published another set of predictions Swift was quick to publish again, denouncing the “imposter” and insisting the real John Partridge was dead, just as predicted. This prank not only fooled the public but also effectively ended Partridge’s career as an astrologer.

Just a handful of the millions of pranks pulled over the long history of April Fools’ Day, there’s no doubt that the celebration is engraved in the social consciousness of much of the world.

Podcast episodes about the history of April Fools Day

Articles you may also like

Weekly History Quiz No.222

Who painted Luncheon of the Boating Party in 1881?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.