Reading time: 8 minutes

Hamilton: An American Musical by Lin-Manuel Miranda remains one of the best Broadway musicals of all time. Of course, as with any art depicting history, there are some discrepancies for the sake of entertainment value.

One of the most entertaining characters on stage has to be Marquis de Lafayette. While he was an asset to the American revolution, parts of his story are either unexplored or altered. So, let’s dive into the true tale of Lafayette – America’s favourite fighting Frenchman.

By: Jade McGee

His American Beginnings:

In Hamilton, he is simply known as Lafayette, which many simply called him. This is no surprise given that his full name is Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette.

Like our main man Alexander Hamilton, Lafayette was an orphan and craved glory as a soldier. However, Lafayette inherited extreme wealth upon the death of his family. This money allowed him to move from Versailles to the American colonies following the Declaration of Independence.

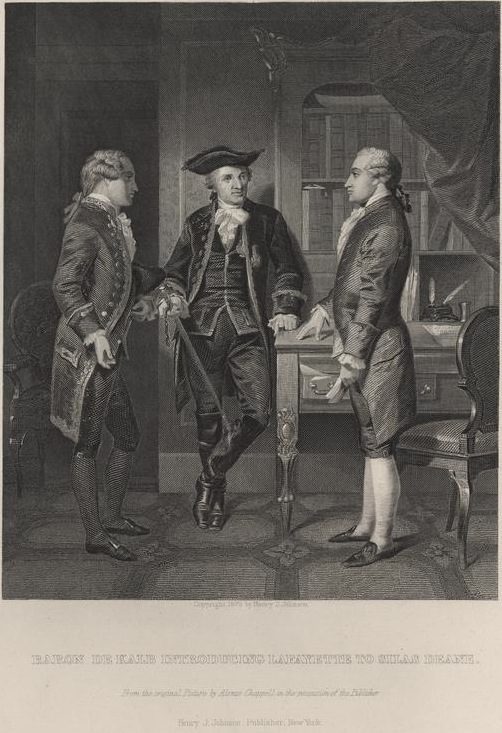

Despite only being a spritely 19-year old with no combat experience, Lafayette was appointed a major general in the Continental Army. When he met George Washington in Philadelphia in August 1777, it’s said the pair bonded almost immediately.

Learning the way of war

Lafayette first experienced combat at the Battle of Brandywine in September 1777. He performed well, despite it being an American defeat. Lafayette was wounded in the leg, however he managed to rally his troops and carry out an orderly withdrawal. This is never an easy task to achieve, and showed his potential as a military commander. After the battle, Washington recommended Lafayette for the command of a division in a letter to Congress, citing him for “bravery and military ardour.”

Independent command

Lafayette was given the opportunity to demonstrate his military skill at the Battle of Gloucester. This was a reconnaissance in force, with Lafayette leading 350 men. They forced back an equal sized Hessian force, obtained the information they needed and withdrew in good order. They had inflicted 60 casualties on the Hessians, while only suffering one killed and five wounded themselves.

Honing his negotiation skills, in 1778 Lafayette convinced the Oneida tribe to join the American army in Albany. These skills were used to their full extent the following year when he returned to France. His mission: convince Louis XVI to send aid to the North American colonies.

Lafayette succeeded, bringing back 6 ships and 6,000 troops – which is referenced in Guns and Ships, a song in Hamilton: An American Musical. Despite his long list of achievements at this point – this is the song where Lafayette receives the most glory.

Yorktown

After his return from France Lafayette spent almost a year organising aid for the American forces from both France and the individual American colonies, as well as proposing various military ventures, including a wildly optimistic plan for capturing New York City. In 1781 Washington ordered him to reform his force in Philadelphia. From there, he and his troops went to Virginia, joining up with Baron von Steuben and his command.

Queue the Battle of Yorktown song from the musical.

Lafayette’s forces were able to bottle up Cornwallis and his troops at Yorktown. Once the French fleet defeated the British at the Battle of the Chesapeake, their isolation was complete. Washington’s forces then joined Lafayette at Yorktown, inflicting a decisive defeat on the British, who surrendered.

After his brilliant efforts at Yorktown, Lafayette became known as the “Hero of Two Worlds.”

It’s here where Hamilton leaves Lafayette’s tale behind. He doesn’t reappear in Act 2, with the actor playing him, Daveed Diggs, taking on the role of Thomas Jefferson. However, his story did not abruptly end after the Battle of Yorktown. Lafayette still had a part to play in the world.

Lafayette’s Act 2

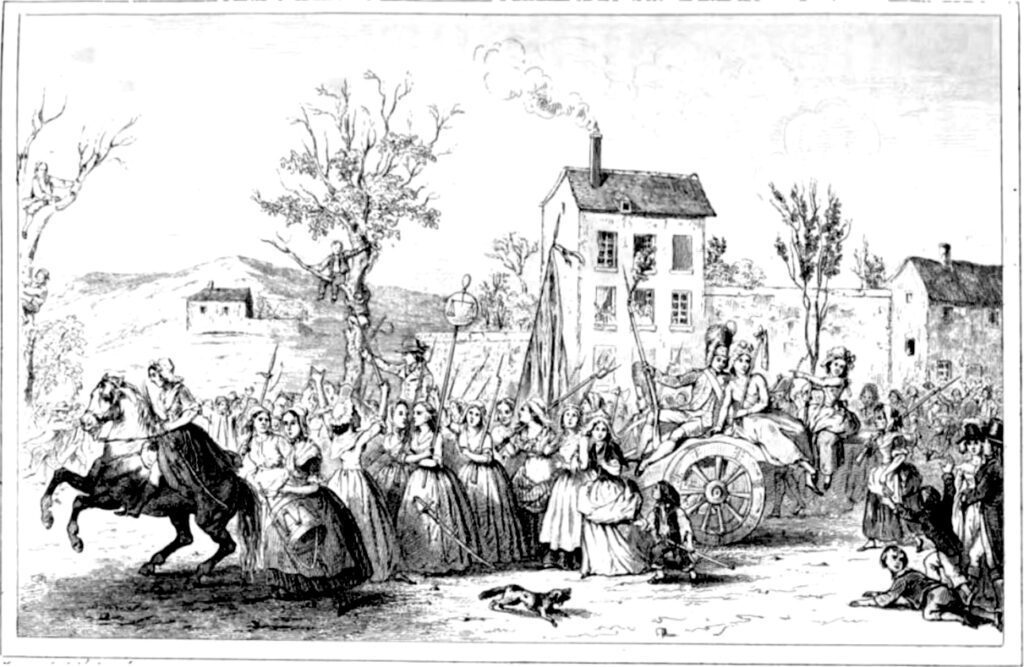

In The Battle of Yorktown, Lafayette’s character states that once the war is won, he’d return to France to join the French Revolution. While he did return to his home country, his involvement in the revolution wasn’t as clear cut, with many describing it as ‘messy.’

Back home in 1789 Lafayette was elected to the Estates General as a representative of the nobility from Riom. Lafayette became the leader of the Fayettistes or the Liberal Aristocrats. Despite his desire for reform, he was not as willing to forgo his aristocratic status, he advocated for a constitutional monarchy.

Quite different from the staunch revolutionary depicted on stage.

Thanks to these conflicting ideals, Lafayette was forced to make several contradictory decisions. For one, he worked closely with Thomas Jefferson to draft the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. He also supported the conversion of the Estates-General to the revolutionary National Assembly.

However, when a mob stormed Versailles following the King’s refusal to move to Paris (as per the National Assembly’s demands), Lafayette and his troops rescued the royal family.

Lafayette was a vocal advocate for transferring power to the bourgeoisie, but he remained against any further democratisation. He even went as far as to fire on a crowd of protestors against the King.

From Hero of Two Worlds, To Citizen of None

Lafayette’s middle way placed him in a very precarious position when the monarchy was completely overthrown. Following a few tumultuous months, he fled to Austria after the revolutionaries captured the royal family. However this was not to be a place of safety for him. The Austrians imprisoned him for his role in enabling the French revolution. This did afford Lafayette the good fortune of not being guillotined during the Reign of Terror.

At the time, his friends in America were working tirelessly to attempt to free him. Jefferson managed to find loopholes to get Lafayette money – this was essentially remuneration for his time as a general during the American Revolution.

Hamilton’s sister-in-law, Angelica Schuyler Church, ended up paying for an escape attempt – demonstrating Lafayette’s and Hamilton’s long-standing friendship. While this escape attempt did fail, Lafayette was eventually conditionally released in 1797 and allowed to return to France, although he was no longer considered a French citizen.

Now paupers, Lafayette and his wife were forced to live quiet lives in La Grange, avoiding politics and the public eye.

Final Years and Legacy

After being regranted citizenship by Napoleon in 1800, Lafayette resisted a return to politics. He was offered and refused several posts, including French minister to the United States. In 1824 he returned to the United States, where he was still wildly popular.

On this Grand Tour, Lafayette visited most of the country. He spoke at the US House of Representatives, the first foreign citizen to ever do so.

Meanwhile, more political changes were occurring in France – King Charles X was forced to step down during the July Revolution. When Lafayette returned to France, he supported Louis-Philippe as France’s new “citizen king.”

Throughout the last four years of his life, Lafayette remained in politics, defending his beliefs until the very end. Lafayette died at 76 on 20 May 1834. He was buried next to his wife in the Picpus Cemetery. His son, Georges Washington, sprinkled soil collected from Bunker Hill upon him.

Lafayette’s involvement in revolutions left a long-standing legacy in both America and France. However, he is better immortalised in the former. His Grand Tour sparked a wave of patriotism, and as a result, several cities were named after him.

To honour him and correct the wrongs of the past, the US government granted him American citizenship in 2002.

While the Hamilton musical’s depiction of Lafayette has some discrepancies, his overall portrayal as ‘America’s Favourite Frenchman’ is rings true.

Read More: WHAT HAMILTON GOT WRONG

Podcasts about the Marquis de Lafayette

Articles you may also like

How Cyprus Became Divided

Reading time: 8 minutes

Cyprus is a country that on paper is whole, but in reality is divided into several parts. Greeks, Turks, Cypriots and the United Kingdom have all staked claims on the island, with the UN in the middle, doing their best to maintain the peace. But what made Cyprus into an island of lines?

How the world failed West Papua in its campaign for independence

Reading time: 6 minutes

At the UN, West Papuan activists sought the support of African delegates who they believed were likely allies. They argued West Papua and Africa shared a history of racial oppression and a desire to see the end of colonialism in all its forms.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.