Reading time: 7 minutes

A relatively unknown name in contemporary Britain, Sir Seretse Khama left an indelible mark on southern African politics. From 1966, he served four terms as the first president of newly independent Botswana. Under Khama, Botswana took immense economic and socio-political strides, leaving a multiracial, democratic, and prosperous nation behind him. He provided a real-world example of how racial equality could function in a part of the world that saw apartheid South Africa just beyond its southern border.

By Jordan Farrell.

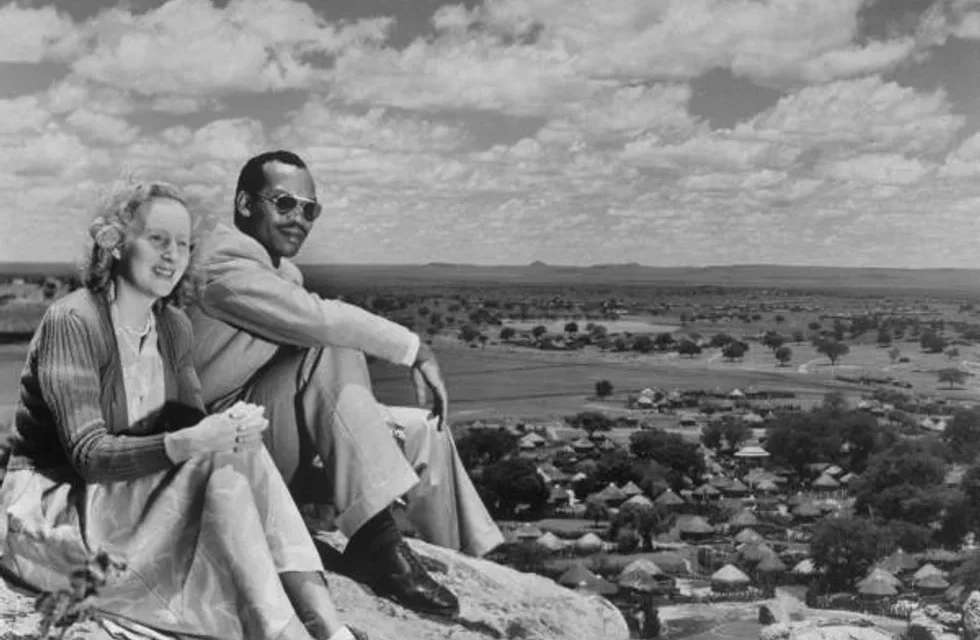

But it was his marriage to a white Englishwoman he met in 1948, while studying in London, that underpinned what was to come. Their remarkable love story not only established these foundations, shaped his image at home and abroad, but also instigated a diplomatic storm with potentially catastrophic ramifications. A file on Seretse Khama at The National Archives provides a unique insight into this story and shows how their marriage was seen as a threat to the Commonwealth itself.

Seretse Khama’s early years

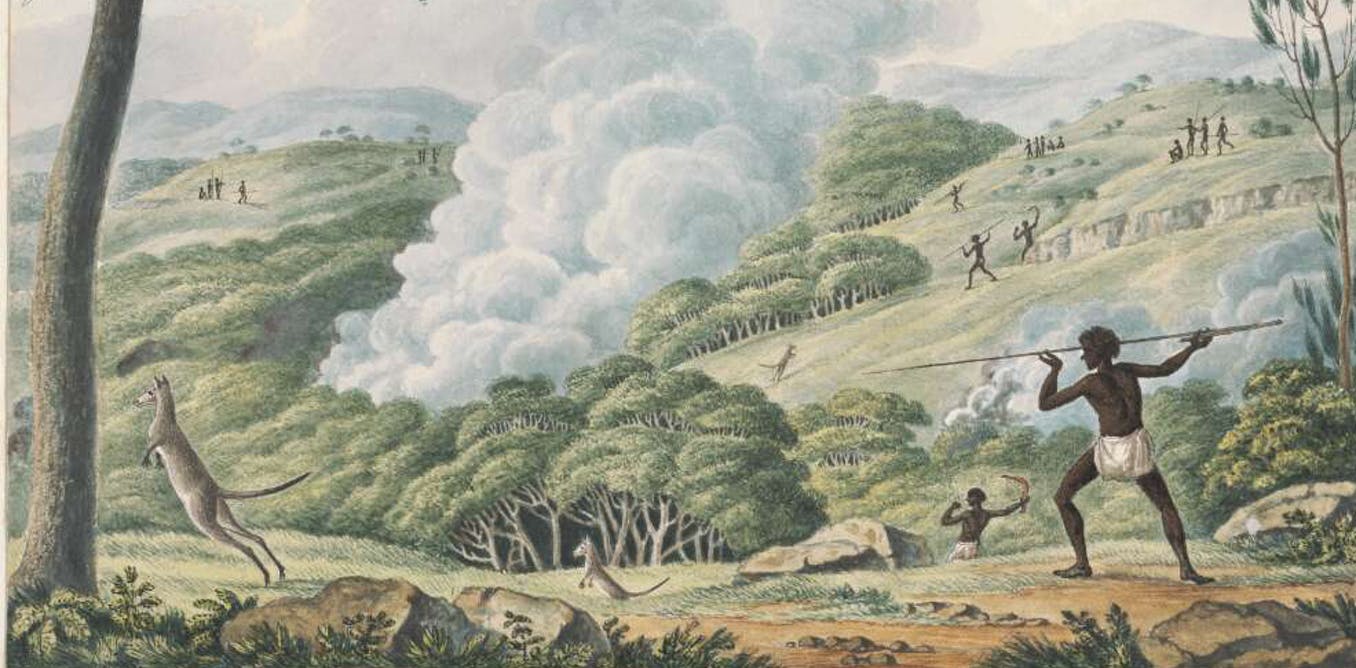

Born in 1921, Seretse was the son of King Segkoma Khama II, chief of the Bamangwato people in the British Protectorate of Bechuanaland, now Botswana. Segkoma died in 1925, when Seretse was an infant. Subsequently, Seretse’s uncle Tshekedi Khama was appointed regent and Seretse’s guardian. Once old enough, Seretse was sent to England to study law at Oxford followed by the Inner Temple in London for his bar examinations.

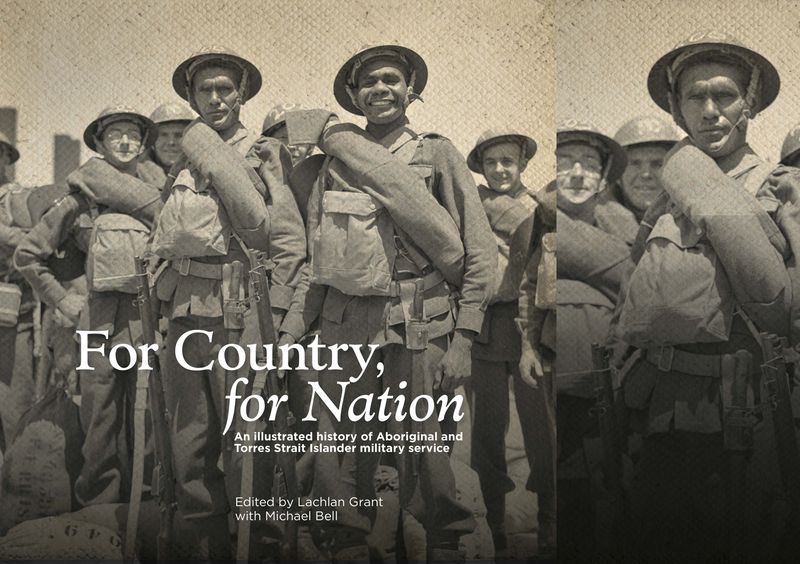

It was in London Seretse met Ruth Williams, an Englishwoman from Blackheath, south London. Ruth, who had served in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force during the Second World War, worked as a clerk at an insurance company at Lloyd’s of London, and after meeting at a dance, the pair fell in love. After some time together they decided to marry. On 30 September 1948, the couple strolled out of a Kensington registry office, having officially tied the knot.

‘This marriage would be resented’

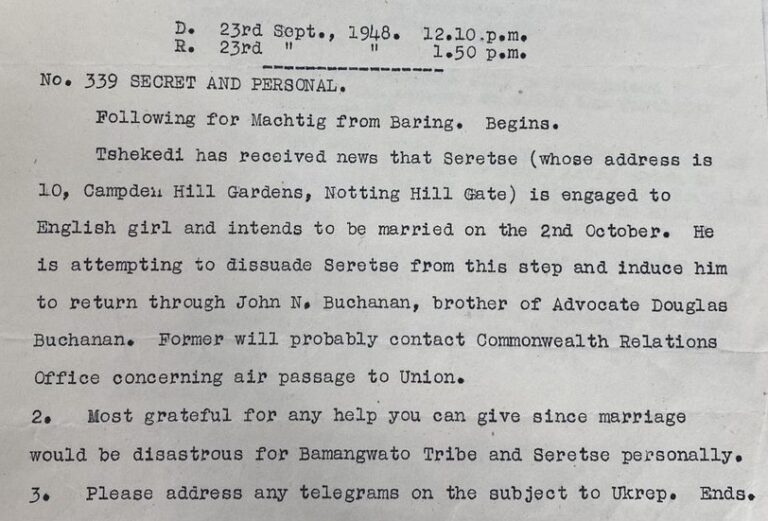

Tshekedi was incensed to learn of Seretse’s engagement and sought to dissuade him. Tshekedi had good relations with the British Government ‘having been an indispensable collaborator in the ruling of Bechuanaland’, and he attempted to use his influence to ask the Commonwealth Relations Office (CRO) to prevent the marriage (see footnote one). A secret inward telegram to the CRO revealed how Tshekedi:

‘considers that this marriage would be resented by the tribe and adversely affect their acceptance of Seretse as chief.’

At this time, the 1936 abdication of Edward VIII still lingered in the British consciousness and a certain responsibility was expected when it came to matters of royal marriage.

Events on the ground in Bechuanaland were also a cause for concern, as demonstrated in two memorandums sent to the Colonial Office detailing ‘the Law and Custom in connection with Seretse’s marriage.’ The first claimed the marriage was illegal according to local customs arguing it ‘indicated a lack of responsibility.’ It stated Ruth would never be accepted into their society and her presence in Bechuanaland would ‘ensure serious danger, trouble, and division in the Tribe.’ The second memorandum followed similar lines, suggesting Ruth would not be accepted and should not come to Bechuanaland for the sake of peace.

Seretse’s return

Three weeks after the wedding, Seretse travelled home to explain himself to his people. It was the first of three kgotla (tribal meetings). The first two resulted in deadlock after Seretse was ordered to choose between his wife and his chieftainship. He refused to agree to the demands.

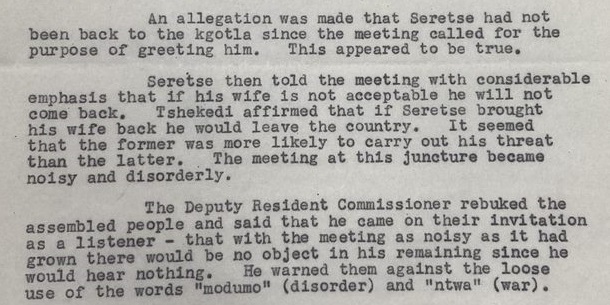

The files held at The National Archives on Seretse include notes from the second meeting in December 1948, written by the district commissioner who was present. They detail how Seretse ‘told the meeting with considerable emphasis that if his wife is not acceptable he will not come back’. It was also revealed 79% of those present fully supported Tshekedi and opposed the marriage. The meeting was said to be ‘noisy and disorderly’, and the commissioner had to warn those present about carelessly throwing around the words ‘modumo’ (disorder) and ‘ntwa’ (war). Tensions were rising.

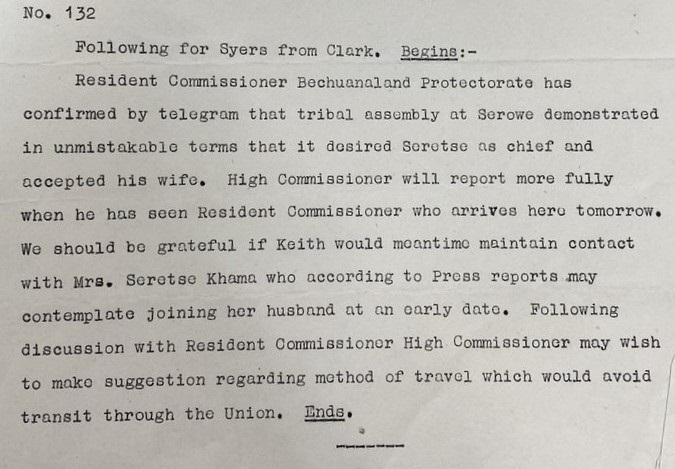

However, a combination of Seretse’s refusal to return without Ruth and rising suspicions of Tshekedi’s motives saw a complete reversal of opinion at the third kgotla, the following June. A secret telegram from the CRO detailed how the tribal assembly had demonstrated in ‘unmistakable terms’ it now desired Seretse as chief and accepted his wife.

The South African government lobby

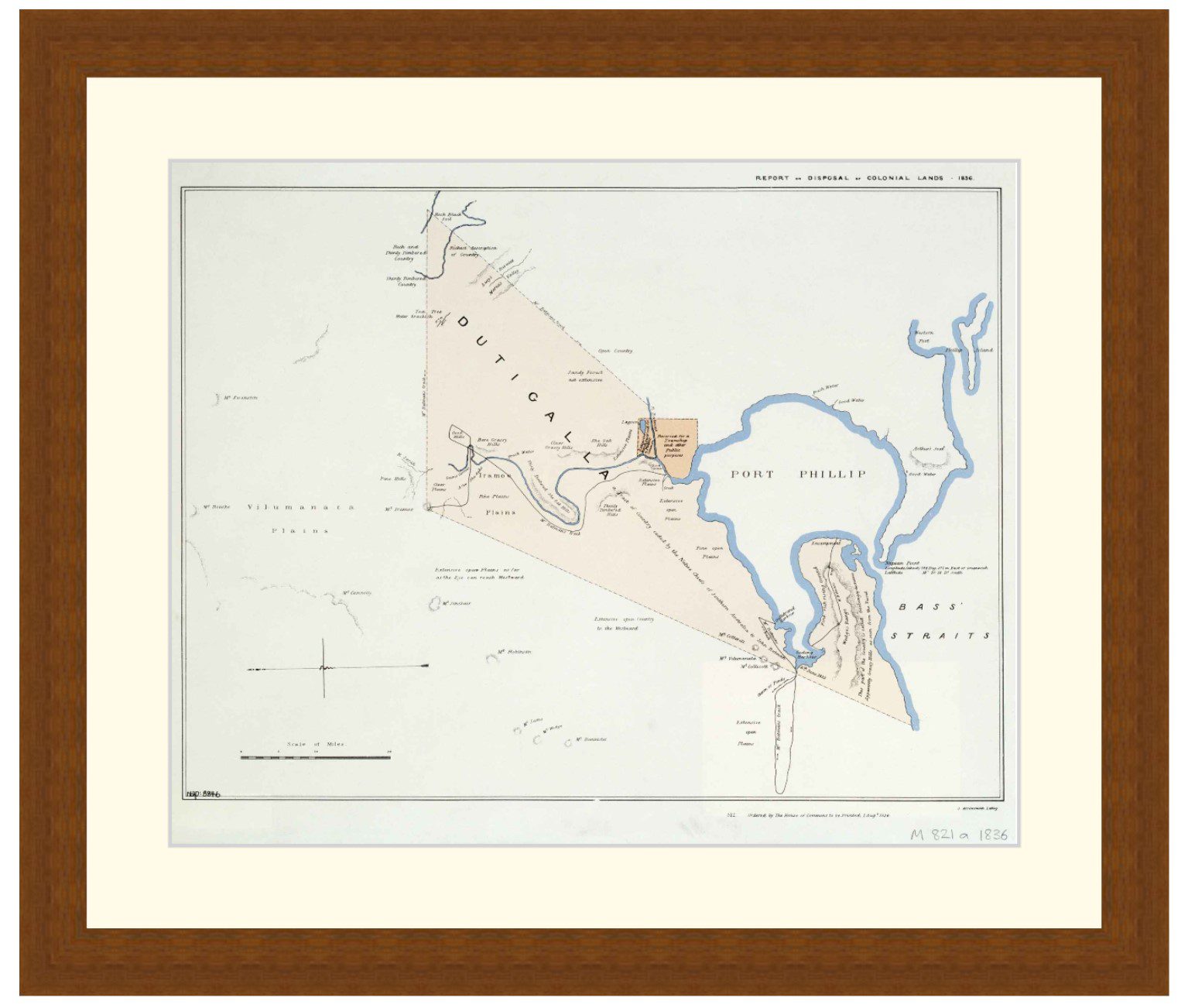

But, any relief felt by Seretse, Ruth, or the Colonial Office would be short-lived. On 24 June 1949, the very date the kgotla accepted the marriage, across Bechuanaland’s southern border, the South African House of Assembly passed the Mixed Marriages Bill, strictly prohibiting interracial marriage. Given that Seretse’s formal designation as chief was subject to British recognition, the South African government set about to immediately lobby against it.

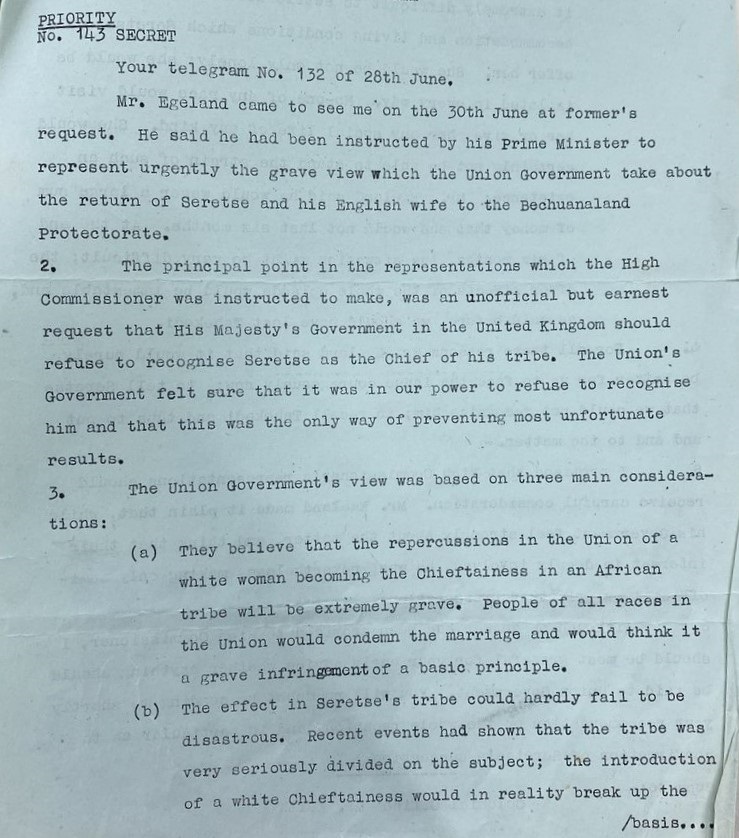

On 30 June, the South African government sent High Commissioner, Mr Egeland, to visit the secretary of state for Commonwealth relations on a ‘semi-official’ or ‘private’ representation. An outward telegram from the CRO explained Mr Egeland ‘had been instructed by his Prime Minister to represent urgently the grave view which the Union government take about the return of Seretse and his English wife to the Bechuanaland Protectorate.’ This placed immense pressure on Britain and the political consequences were potentially catastrophic.

The Commonwealth at stake?

The British government feared South Africa would escalate tensions by imposing economic sanctions or even launch a military incursion into Bechuanaland. But, to not recognise Seretse would be seen as ceding to the prejudices of South Africa as well as ignoring the wishes of the Bamangwato people. It was also thought some in South Africa would use the occasion to push for the establishment of a republic outside the Commonwealth. The Commonwealth itself, in southern Africa at least, seemed at stake (see footnote 2). The British government succumbed to this pressure following a judicial enquiry, the report of which was suppressed, and Seretse and Ruth were exiled from Bechuanaland in 1951.

The pair were denied entry to Bechuanaland until 1956, when they were permitted to return as private citizens. Seretse’s treatment at the hands of the British government made him a cause célèbre, helping propel forward the formation and growth of the Bechuanaland Democratic Party and his successful presidential campaign in 1965.

The name Seretse translates to ‘the clay that binds.’ It is both apt and ironic. Initially, Seretse’s union with Ruth Williams did anything but bind his tribe together and drove a wedge between Britain and the Union of South Africa. But his love and dedication for Ruth prevailed and his story helped carry Bechuanaland on the road to independence.

Jordan Farrell is a Public History MA student of Royal Holloway, University of London. This blog is part of a collaboration between The National Archives and the university to promote research and writing based on our records.

Footnotes

- Ronald Hyam, ‘The Political Consequences of Sertese Khama: Britain, The Bangwato and South Africa, 1948-1952‘, The History Journal, 29.4 (1986), 921-947 (p 924)

- Ibid, p 926-927

Further reading

- Clare Rider, ‘The “Unfortunate Marriage” of Seretse Khama‘ (2002)

- Chioma Echebiri, ‘Who Was Sir Seretse Khama?‘, The Republic (22 November 2021)

This article was originally published in The National Archives.

Articles you may also like:

Weekly History Quiz No.218

When did the construction of the Acropolis of Athens begin?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

Weekly History Quiz No.255

1. Who painted Liberty Leading the People in 1830?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.