Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

By Dr Robert T. Foley.

How do Germans view the Battle of The Somme? This article explores reactions to the most famous battle of the First World War.

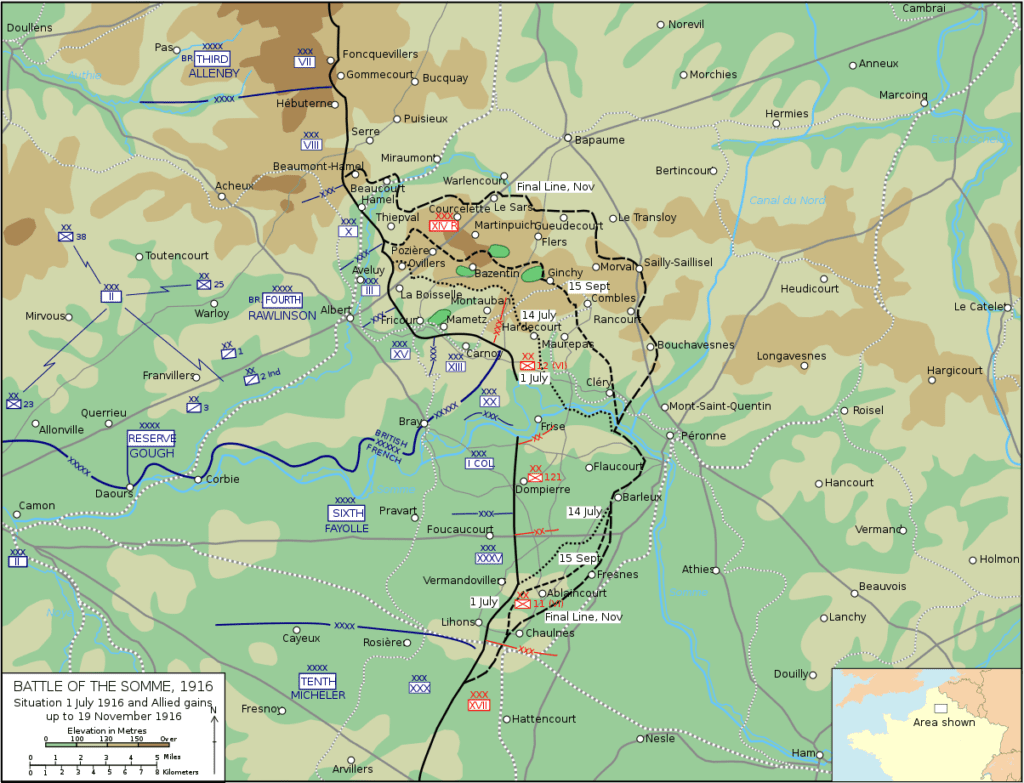

Shortly after daybreak on 1 July 1916, around 100,000 troops of Sir Henry Rawlinson’s 5th Army left their trenches and advanced on the German trenches across no-man’s-land. Many, if not most, expected the 5-day artillery bombardment to have destroyed all but the hardiest of German defensive works and to have killed, wounded or stunned the German defenders. In short, they expected to walk into the German lines largely unopposed. However, as we know today, the attack was anything but the walk-over expected.

The massive British artillery barrage had damaged the surface of the German defenses, but most defenders survived unharmed in dug-outs (known in German as Stollen) deep below the surface. When the barrage ended and the British troops attacked, the shaken but unharmed German defenders emerged and poured a deadly fire into the advancing lines of British troops. By the end of the day, the German defenders had inflicted one of the most stunning defeats on any army.

Close to 60 percent of the British attackers were dead, wounded or missing, and in most places along the 5th Army’s front, the surviving attackers were forced back to their starting points. However, the attack on 1 July was only the beginning. Although the Germans emerged victorious on this day, over the next 4½ months, the battle would ebb to and fro, all the while the three armies involved, the British, French and German, would suffer horrible casualties.

Initially, the Anglo-French attack on the Somme was welcomed by the German high command. Erich von Falkenhayn, the Chief of the German General Staff and the de facto commander-in-chief of the German army, had been long expecting the attack. In February, he had launched an assault on the French fortress of Verdun that was designed to ‘bleed white’ the French army and force the French government to peace talks. Falkenhayn believed that before the final French collapse the British would launch an offensive of their own, designed to relieve pressure on their beleaguered ally.

Given the disastrous performance of the British army in previous offensives, the German general believed that this new British offensive would also be easily defeated. After this, Falkenhayn intended to launch an offensive of his own that would possibly drive the British from the Continent and force the French to concede defeat. The results of 1 July seemed to confirm this critical assessment of the British.

From 2 July until 13 November, the British and their French ally continued to attack. While on 1 July the British had planned a war-winning advance, after the shock of the initial assault, the British changed their tactics. Learning the lessons of 1 July, they would generally employ more methodical methods in an effort to achieve more limited results for the remainder of the battle.

Rather than attempting to achieve a decisive breakthrough of the German lines, the British army instead aimed at capturing pieces of terrain – woods, hills, villages, etc. – that were key to the successive lines of trenches that made up the German defensive position. To take these terrain features, the British relied heavily on intense artillery bombardment of a limited area.

They also applied more widely creeping barrages, during which the infantry would follow close behind a slowly advancing wave of artillery fire for protection against the German defense. All of these factors slowly took their toll on the Germans. Weeks and months of heavy artillery bombardments battered down the German defensive works, caved in the deep Stollen, and killed German defenders. The battle had shifted from being an attempt to break through the German line and win the war quickly to a slow attritional battle designed to kill and wound German soldiers.

The British were helped in their goal to kill and wound as many German soldiers as possible by the Germans themselves. At least in the initial stages of the battle, German practice was to hold all ground and to retake any position if it were lost at any price. This resulted in at least some German units packing the front trenches with troops in an effort to hold them.

The trenches closest to the British lines could often be seen by British artillery observers and consequently bore the brunt of the artillery bombardment. Closely arrayed in the front trenches, the German defenders were vulnerable to this artillery fire. Further, when the British did seize portions of the German trench line, the German infantry inevitably counter-attacked to take back the lost positions.

During these counter-attacks the German troops were often forced to leave the comparative safety of their trenches and suffered high casualties accordingly. Indeed, German troops were shocked by the weight of artillery fire used by the British and generally believed that they were losing this Materialschlacht, or battle of materiél.

The ferocity and the duration of the Anglo-French offensive on the Somme surprised the German high command. The casualties suffered during the long battle forced Falkenhayn to abandon this idea of a counter-offensive. Indeed, the British attritional tactics were extremely effective at wearing down the strength of the German army and gobbled up German reserves:

Between 1 July and the battle’s end on 18 November, 90,00 German divisions served on the Somme front. During the height of fighting, German divisions could only last around 2 to 3 weeks on the front before having to withdraw to rest and refit.

However, contrary to what the British commander-in-chief, Sir Douglas Haig, argued at the time and some historians have argued since, the battle did not force the Germans to abandon their offensive on Verdun; the decision to slow this offensive had been taken before the Anglo-French attack. Moreover, the Germans still had a sufficient reserve of forces to send a number of divisions from the Western to the Eastern Front to face the Romanians when they entered the war in August.

Along with all armies that fought in the battle of the Somme, the German army suffered greatly. As each army calculated casualties by different means, estimates of the numbers of dead, wounded and missing have been a matter of great debate since the war itself. Estimates of the German losses vary from 420,000 to 630,000.

However, despite these heavy losses, the battle of the Somme can be seen as a German victory. The Entente forces were unable to break through the German defence and were unable to achieve the victory for which they hoped in July. Further, as the British army had, the German army learned valuable lessons from the experience. By the end of the battle, they had developed a more flexible defence in depth that was not dependent on holding forward positions at all costs.

This defensive system allowed them to absorb the continued Anglo-French attacks both during the battle of the Somme and in the battles of 1917. Additionally, the battle forced the German high command to face up to at least some of their deficiencies in the technical realm. Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff, the team that took command of the German army after the Romanian entry into the war forced Falkenhayn’s resignation, developed an ambitious building program that re-equipped the German army with modern artillery and aircraft. Thus, despite the horrific casualties, the German army emerged from the battle of the Somme an even more formidable foe than before the battle.

Articles you may also like

The Long Tail of the First World War

Fallen Empires and Civil War By Caitlan Hester The popular view of the First World War is that it ended with Armistice in 1918. But the end the First World War did not put an end to conflict and combat. The 1918 Armistice was followed by events that radically shaped today’s geo-political landscape: the spread […]

How Romania’s WW1 Gamble Paid Off Spectacularly

Reading time: 6 minutes

The Great War was a major turning point for virtually all European countries, but not too many of them enjoyed a positive outcome. Although it took two years for Romania to enter the war and another two for the conflict to reach a conclusion, the result was an unlikely unification of its historical lands and the beginning of the most prosperous period in the nation’s history.

Body text – Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 : The Open University