Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

The history of the Dutch East Indies is a blood-soaked tale of war and subjugation in the name of national honour, though in the background it was lucrative spice trade that was the real motivator. In this article, we’ll lift out one particular aspect of this 350-year-long saga, and talk about the Aceh war, one of the longest military conflicts ever fought by the Dutch.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

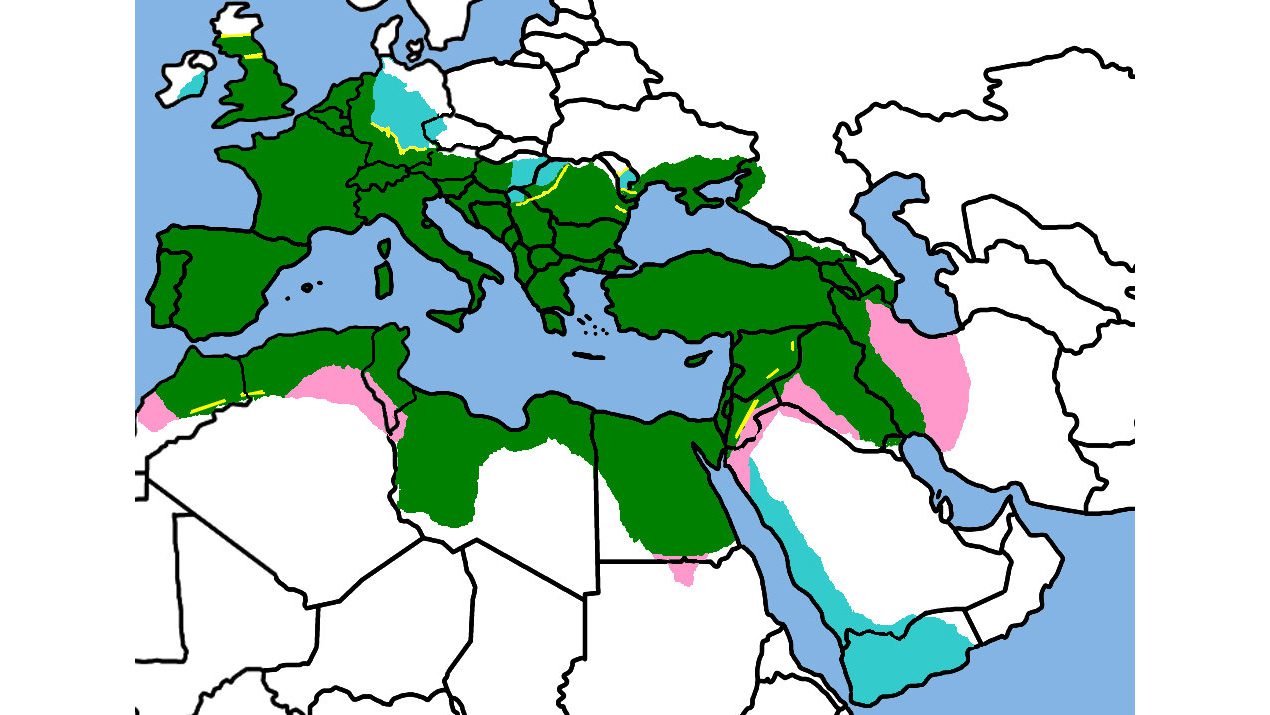

When the Dutch arrived in what’s now called Indonesia in the very late 1500s, the archipelago wasn’t one cohesive whole. Instead, much like, say, India or Europe, it was split into dozens of smaller states, some more powerful than others. The Sultanate of Aceh was just another one of these statelets, officially a vassal of the Ottoman sultan.

Much like with British rule in India, the Dutch in the East Indies relied on an indirect system of governance fuelled by divide-and-rule tactics. Though there was some direct rule, most of the archipelago was governed by indigenous rulers who were forced to listen closely to their Dutch advisors. By maintaining rivalries between princelings and staying behind the throne, the Dutch were able to control this massive territory and control its supply of natural resources, most importantly spices.

British Guarantees

Aceh, however, maintained its independence until the late 19th century thanks to having its independence guaranteed by the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824. Until 1824, Britain had considerable influence on Sumatra, which it gave up for concessions in Malaysia. The British did, however, negotiate for the Sultanate’s continued independence.

In 1871, however, the Dutch and British concluded a new treaty in which Britain gave up Aceh’s independence in return for the free use of Sumatran shipping lanes. This was the green light for The Netherlands to invade and claim the Sultanate’s pepper — about half the world’s production — for itself.

The Dutch Invasions

The pretext for the war was found in negotiations the Sultanate had held with other foreign powers, notably the United States, but, as this article explains a lot better than we can, it was all a smoke screen. The Netherlands wanted more territory and the pepper and oil it contained.

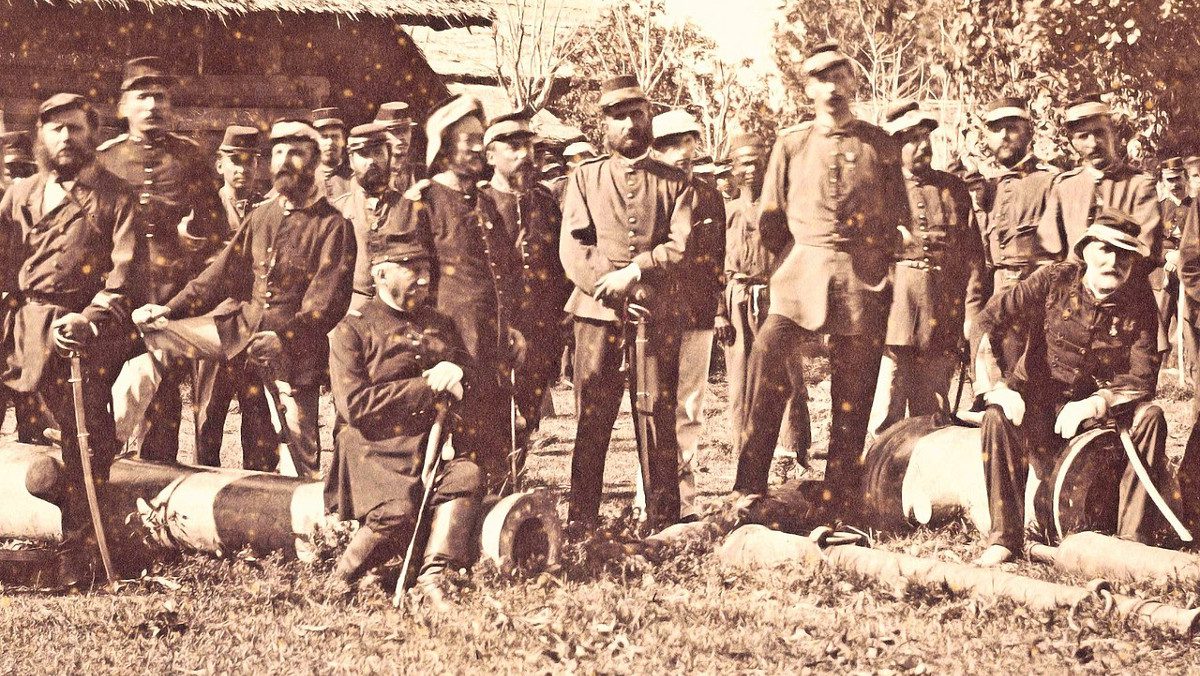

The invasion started in March 1873, but it quickly stalled out. The Dutch had seriously underestimated the Acehnese forces, which had rapidly modernized with the help of other Western powers, and had brought far too few men and no artillery. After some minor skirmishes which cost the lives of about 80 men and the force’s top commander, the Dutch retreated and installed a naval blockade of the Sultanate itself.

In November, after the Dutch had bandied the blame for the failed expedition about in a flurry of paper, a second invasion was staged, which proved more successful. The invaders came better prepared this time and captured the Sultan’s palace in Banda Aceh, the nation’s capital. Victory was declared, but it was a hollow one: much like in, say, Afghanistan in the 21st century, the Dutch held the capital, but the overwhelming majority of the nation was still controlled by the indigenous forces.

Guerilla Campaigns

Like in Afghanistan or Vietnam, what followed was a long period of on-and-off warfare, fought exclusively by guerillas. In an interesting analog to present-day, one of the ways in which the Acehnese, by and large devout Muslims, sustained their struggle is by declaring it a holy war against an infidel invader.

Though this article is too short to go into the details of the guerilla campaigns, what is interesting to note was how the Dutch slowly but surely extended their control over Aceh, though they never would control all of it, and their rule was never exactly stable; a recurring theme in asymmetrical warfare.

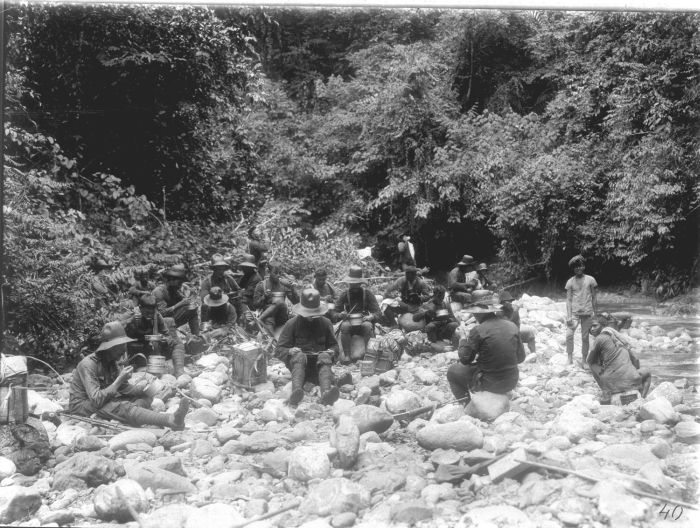

The first method involved the usual divide-and-conquer approach: using troops from other islands, especially the Moluccas and Ambon, who had no empathy toward the Acehnese but were familiar enough with the type of terrain in Aceh and the tactics used by the guerillas. Through targeted attacks as well as scorched earth campaigns, many Acehnese were brought to heel.

Of course, an army is only useful if you have the right target to point at, and this is where the story gets an interesting twist in the form of a man named Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje, a Dutch aristocrat who converted to Islam while studying Arabic.

His biography deserves a few articles of its own, but his role in the Aceh wars is interesting. As a famous scholar and fellow muslim, he was able to cozy up to the Acehnese leaders and gain their trust. In a rather spectacular betrayal, he then gave all the information he gleaned to the Dutch authorities, who used it to launch several nasty punitive expeditions that stamped out much dissent. To this day, his name isn’t particularly popular in either Aceh or Indonesia as a whole.

Pacifying the Unpacifiable

In the end, and end to hostilities in Aceh was proclaimed in 1880, 1898, 1904 and 1914, showing that the Dutch at no point truly held sway over the territory (they were also distracted by their neutrality during WW1). In fact, pockets of resistance held out until the Japanese invasion of 1942, when the remaining resistance fighters decided to fight these new invaders, instead.

Even after independence, the Acehnese didn’t feel at home in the new Indonesian state and ended up fighting an insurgency between 1976 and 2005, which was only ended by concessions towards autonomy for the province. It seems that nobody is able to control Aceh, except for the Acehnese.

Articles you may also like

The Battle of Kadesh and the World’s First Peace Treaty

For a shining example of ancient warfare and the cause of the world’s first recorded peace treaty, look no further than the Battle of Kadesh. By Madison Moulton. The characteristics of ancient warfare are often shrouded in mystery. There is evidence of the existence of early warfare, but intricate details of battle are scarce. However, […]

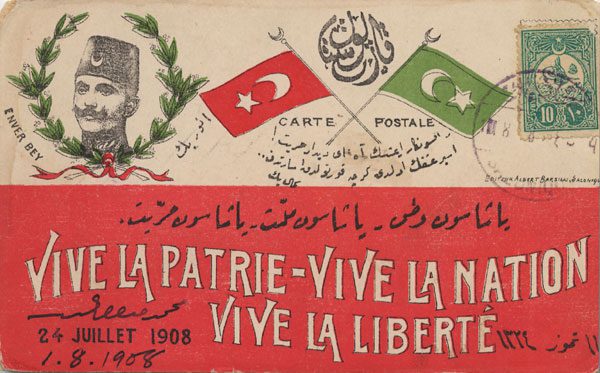

A Period of Change: Global Events in the Lead Up to WWI

The history of the lead up to WWI is undoubtedly dominated by Europe. European powers understandably take centre stage, given their influence on the start of the Great War. However, the years before WWI were a period of change – not just in Europe – but all over the world. Revolutions, wars, and political upheaval […]