Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

By Madison Moulton.

The causes of global inequalities between the West and the East is a great debate among historians. This phenomenon – the rise of the West and the supposed ‘reversal of fortunes’ of the East after 1750 – was deemed the ‘Great Divergence’ by Samuel Huntington in the 1990s. In recent years, the Great Divergence debate has attracted a number of scholars presenting their theories for the differences between ‘the West and the Rest’. No theory is widely accepted; which argument is more compelling is up to the individual to decide.

Theory 1: The West is Best

The initial literature on the Great Divergence describes the rise of Europe as a completely internal process. Scholars David Landes, Allen MacFarlane, and Niall Ferguson argue that the West’s unique cultural and social life gave the region the ability to break away from others and become the dominant economic power. Some of these unique characteristics include rationalization; the scientific method; a culture that promotes labour, discipline, freedom, and knowledge; individual property rights and a free-market economy; inventiveness; and individualism.

Scholars ascribing to this theory have been accused of bias and Eurocentrism (seeing the world through a European lens). However, Landes has not denied this charge and believes the unique nature of the West necessitates a Eurocentric view. Other charges include the focus on the positives of the West while ignoring external factors like imperialism and the appropriation of resources from other continents. And, critics claim the comparison between regions like Britain and China is unfair due to massive differences in territory and population.

Theory 2: Eastern Appropriation

On the opposite end of the debate, some argue Europe’s rise was not internal but facilitated by Eastern appropriation. John Hobson and Andre Gunder Frank begin their argument by denouncing the Eurocentric claim that Europe pioneered its own development. Instead, they believe Europe’s success resulted from the appropriation of ideas, technologies, institutions, and resources from the East. Oriental globalisation was therefore the precursor to the modern West. Taking it a step further, Frank argues the global economy has always been characterised by Asian dominance – the current success of the West is a temporary event achieved through luck and violence.

In their attempt to discredit the Eurocentric school of thought, some argue the Eastern Appropriation theory leans too far in the other direction. Instead of Eurocentrism, critics believe these scholars are guilty of Sino-triumphalism. They focus on the negatives of the West and the positives of the East. And, they describe an Asian-centred global economy without a holistic analysis of the facts.

Theory 3: Coincidence

Stepping away from Eurocentric and Sinocentric thinking, historian Kenneth Pomeranz joined the debate with his book The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy published in 2000. Pomeranz presents a wildly different view of the rise of global inequalities in which coincidence plays a major role.

While scholars of previous theories date the Great Divergence to 1750 or earlier, Pomeranz argues that the decline of the East only occurred after 1800, before which the West and the East were strikingly similar in modernization and development. After 1800, capitalism and the industrial revolution arose out of necessity, not intention or innovation as other scholars claim. China was always rich in natural resources, but Europe suffered from a lack of energy and raw materials. Europe’s response to this dilemma was to develop industrial technology and initiate colonisation to obtain raw materials. Pomeranz believes this gave Europe the advantages it needed in technology and trade to become the dominant power.

This theory has been praised by many historians, including Andre Gunder Frank, who claim it provides a more complete picture by relying on various factors and contingency over unitary explanations. Historians agree his analysis has brought a 1990s discussion up to date and provided compelling evidence that few can ignore. However, as with all fervent discussion, it is unlikely to end the Great Divergence debate for good.

Other explanations

Many scholars have thrown their hat in the ring in recent years, producing a wide range of theories. Jared Diamond uses an environmental approach to discredit views that attribute the Great Divergence to cultural differences and biological determinants. Diamond argues that geography and climate were the main forces behind Europe’s dominance and that the environment had the greatest role to play.

Even before the term ‘Great Divergence’ was coined, scholars were analyzing the success of the West. Economist Adam Smith argued higher wages caused the gap, improving standards of living and technological advancements. Another theory mentions (among other things) political geography: Joel Mokyr argues the separation of Europe into smaller independent states resulted in faster development than large unitary states like China. Each explanation has its pros and cons, yet to provide a complete answer.

The Great Divergence debate has been a central discussion among historians and history enthusiasts for the past 25 years. The lack of a completely compelling and widely accepted view means the debate is likely to continue unsolved. Perhaps the answer is one theory, perhaps it is a synthesis of all theories – the answer is up to the individual historian to argue.

Other Articles you may like

Why the Legions Beat the Phalanx

The societies of ancient Greece and Rome valued brawn as well as brains. Philosophers fulfilled military service and some of the most masterful speeches held in the senate or agora argued for war. However, it was the Romans that would end up dominating the Greeks, which was largely to do with the way they fought […]

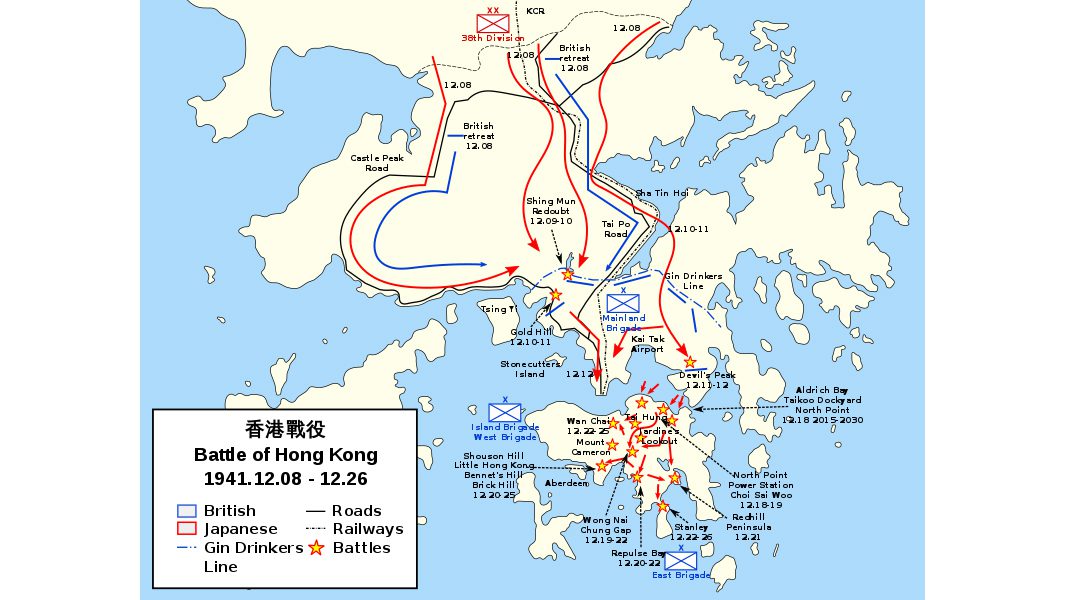

The Battle for Hong Kong – London’s Lost Cause?

Within 12 hours of Pearl Harbour being bombed by the Japanese at the outset of their entry to World War 2, they began their invasion of the British Territory of Hong Kong on the 7th December 1941. The British didn’t just roll over as is assumed but instead followed Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s command – […]