By Thomas Suddendorf, The University of Queensland and Michelle Langley, Griffith University

Today, bags are everywhere — from cheap canvas ones at the supermarket to designer handbags costing up to US$2,000,000.

But archaeological evidence shows we have been using mobile containers — bags and other carrying devices — for tens of thousands of years.

Before sedentary life took root after the end of the last ice age (around 12,000-years-ago), people hunted, fished, and gathered everything they needed for day-to-day life.

Without bags, such a lifestyle would have meant only a couple of tools could be kept on the body at any one time. Anything else would have to be made when and where it was needed, or left at strategic locations.

With carrying devices, our ancestors could carry many tools and there was a benefit in making tools in advance — even those only used occasionally.

Consider the 5,300-year-old frozen man found in the Ötztal Alps in Tyrol, Italy, in 1991.

Ötzi carried dozens of tools in his quiver and string and birch bark baskets, including an axe, a bow-and-arrow, a dagger, medicinal fungi, and a fire-making kit. A pouch sewn to his belt contained small tools including a drill, an awl, and a scraper.

Carrying such tools was a major advantage in allowing humans to be prepared for unexpected events.

When did humans invent mobile containers?

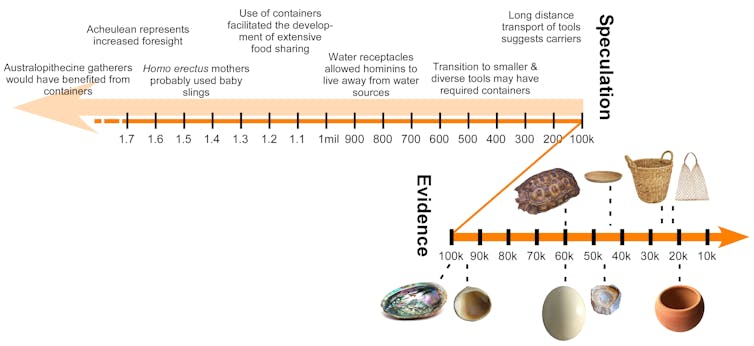

We recently reviewed the archaeological record for the earliest signs of mobile container use in humans.

Indicators of baskets, nets, and pots reach back some 30,000 years, with containers made from wood and stalagmites made some 50,000-years-ago.

Earlier this year, a study reported a small piece of 3-ply cord made from inner bark fibres found at a Neanderthal site dated to between 41,000 and 52,000 years old. This could point to the creation of bags and the weaving of baskets.

Natural containers, such as shells, were used much earlier by both modern humans and Neanderthals: archaeological sites at Blombos Cave in South Africa and Qafzeh in Israel record the use of shells for holding red ochre more than 100,000-years-ago.

When were bags first invented? Probably a very long time ago.

M.C. Langley & T. Suddendorf.

It is likely the origins of carrying devices are, in fact, much older than we have found evidence for. However, most materials used for making carrying devices – such as hides, barks, and fibres – decompose rapidly and leave no traces behind for us to find.

It is possible older containers will be eventually reported, especially when archaeologists pay more attention to them in their collections.

We suspect that without realising the critical importance of these tools to human evolution, and perhaps because of the association with gathering and “women’s work”, some evidence may have been overlooked.

What about the animals?

Marsupials have pouches to carry their offspring. Pelicans have throat sacks to carry fish to their young.

But do any animals make carrying devices?

Many species use tools, and a few even make tools, such as chimpanzees stripping twigs of a branch for termite fishing. But there is little to suggest these animals retain their tools for future problems, or they have invented carrying devices to keep these tools for a long period of time.

Wouldn’t a bag be a better choice?

Pixar/Walt Disney Studios.

There are a few reports of animals independently using human-made containers, such as a crow transporting food with a cup. Humans have, of course, long attached containers to animals, making beasts of burden carry or pull loads.

The physical capacity to use such tools isn’t in question; just the mental capacity. There is little evidence of animals having the foresight required to recognise the usefulness of containers for future activities.

These donkeys have bags – but they didn’t invent them.

It has pockets!

The emergence of humans using mobile containers at least 100,000 years ago indicates people were increasingly thinking ahead and recognising the future utility of their tools.

This ability may be right at the heart of what it means to innovate.

Humans and other animals constantly solve problems. But once we recognise the potential of using a solution in the future we become motivated to retain and safeguard new tools. We may even be willing to invest time and effort refining those tools further – perhaps sharing them with our friends and family.

In this way, the appearance of mobile containers in the archaeological record can indicate a key cognitive shift in our ancestors: foresight began to drive tool innovation (including further containers) and the evolution of ever more sophisticated material cultures.

Today mobile containers are everywhere. Our clothes have pockets, we have suitcases for clothes, and trolleys for suitcases. We put suitcases in containers and containers on ships. Large mobile containers carry humans across water, through the air, and into space.

Containers in containers in containers.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Mobile containers are so ubiquitous it is easy to overlook the fundamental importance of this basic invention.

These carrying devices allowed our forebears to have tools and resources at the ready wherever they went. The dramatic exploitation of this concept has allowed humans to create a world full of containers transporting endless amounts of stuff — big and small — to where we want it to go.

Without the invention of bags, we’d still be running in the woods with our hands full.![]()

Thomas Suddendorf, Professor, School of Psychology, The University of Queensland and Michelle Langley, Senior Research Fellow, Griffith University

This article originally appeared in The Conversation.

History Guild Members can read more about this in the library.

Direct evidence of Neanderthal fibre technology and its cognitive and behavioral implications.