Reading time: 7 minutes

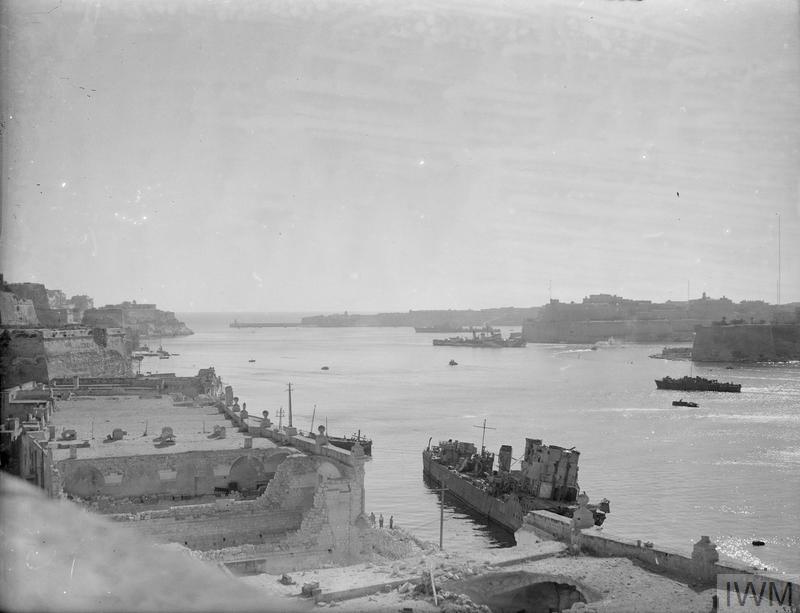

The island of Malta, located in almost the exact centre of the Mediterranean, was an important depot and staging post for the Allied efforts in North Africa and, later, the invasion of Italy. As a result, the Axis forces bombed it relentlessly for years, something you can read about more in our article on the Siege of Malta through Australian eyes.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

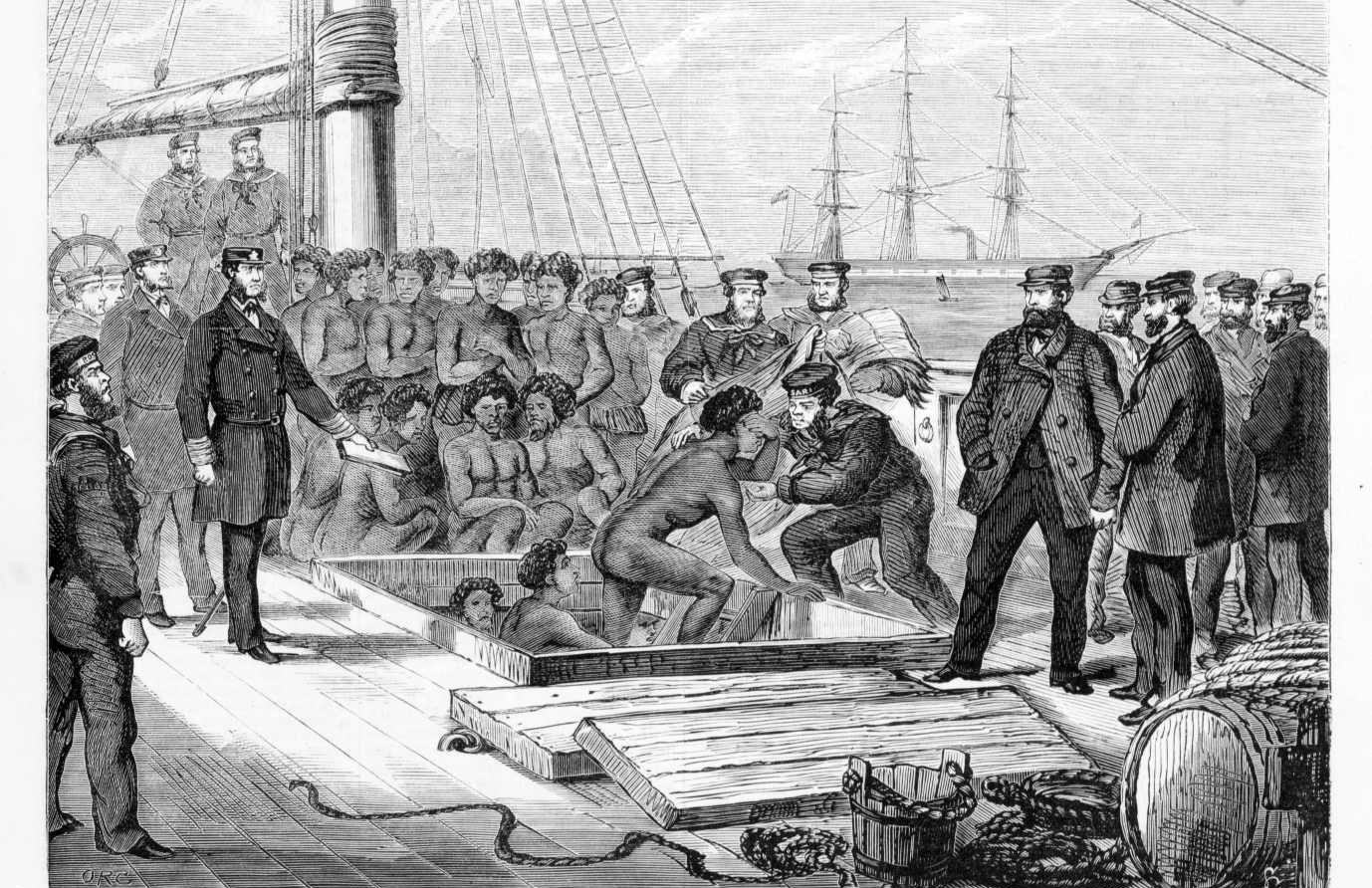

Just as important as the men and women fighting on the island, or the planes defending it from the air — read about the Australian pilots who served on Malta — were the ships that supplied the island and kept it up and fighting. In this article, we let Australian sailors who served in the convoys tell their stories.

As is always the case with articles about Australians in the Med during WW II, we owe a debt of gratitude to the Australians at War Film Archive, a massive trove of interviews with Australian veterans of all wars the country has been involved in.

“A garage for the fleet”

Located as it was, Malta served as the “garage for the Mediterranean fleet” in the words of Oriel Ramsay from Perth, a sailor who served on the HMAS Sydney, a ship we featured in our article about the Battle of Cape Spada. Because of this role, it was vital to supply the fleet that operated from there as well as the efforts that defended it.

Merchant seaman Ronald Ware from Wamberal, NSW, somebody who we’ll see a lot more of further down in this article, remembers the kind of goods being shipped. The first leg was up to Britain, where they delivered beef from Australia and cheese, butter and wool from New Zealand. Once in Britain, they stocked up on more more martial cargo:

[In] Liverpool they were loading us up then and it was pretty clear we were going to somewhere hot and they were every hold in the ship had a cross section of all the cargo. It was not all of this in in that hold or that in another. We had bombs and artillery. We had anti aircraft shells. We had depth charges. We had small arms and Bofors [an anti-aircraft gun] anti aircraft shells and then on top of that we had food and supplies and sometimes it was a mix.

To keep these supplies from reaching Malta, the Axis forces set out to force the island’s surrender, bombing the “shit out of Malta” (in the words Mr. Ware), as well as attacking any and all shipping in the Mediterranean. With the RAF preoccupied with the Battle of Britain, the Italian, and later German, air force had free rein to do pretty much as they wanted, at least until efforts could be made to shore up the defences of the island.

As a result of the Axis attacks on convoys, very few ships made it through to Malta. According to Mr. Ramsay, one convoy of 53 ships had only 10 arrive, almost all of them the victim of air attacks — while there definitely was U-boat activity in the Med, the German wolf packs were mostly active in the North Atlantic.

However, Ramsay says, morale remained high: “we knew things were damn tough, and we were doing it damn tough. And we would have sympathy for all the blokes that weren’t, that were getting knocked off, getting sunk.”

Escort duty

Even if morale was high, though, protecting convoys was hard, terrifying work. Frank Smith from the Riverina served on multiple ships during the conflict in the Med and describes what it was like to screen for a convoy.

We screened a Malta convoy. In other words screening was that you took the flak off the convoy and I think that was one of the successful convoys. I think four ships got through on that convoy, which was pretty good because probably 12 started out but we took the flak for that.

According to Mr. Smith, the trick to a successful convoy screening was for the military vessels to actually not be too close to the merchant ships. During his training a lecturer had told him that the reason the merchant’s went unprotected even with heavier ships nearby was because of ego. “You’re getting far bigger praise and more Iron Crosses for sinking a cruiser than you will sinking an old tramp steamer.”

With the job essentially being to draw enemy fire away from the convoy, all they could really do was wait for the Axis to come to them. Mr. Smith explains:

We used to stand around our gun and watch the sea, watch the convoy. You’d see the convoy probably about eight or ten mile away […]The worst part of those actions is the waiting. The yellow flag [enemy aircraft sighted] has gone up and you’re waiting for the red flag [enemy aircraft near] to go up, and you’re nursing a prodigy there. When you’re number one loading number you’ve got it sitting in the fuse setting rack and you’re sitting there, and the old stomach churns up you see? “Christ, how many this time?” You know? So it’s the waiting. Once the action is on you haven’t got time to think.

The red flag goes up and that means that they’re here, and from then on you were just flat out from ready use locker to gun, ready use locker to gun, and the noise is unbelievable, the scream of the turrets and the guns, bombs bursting. I think you’ve got to be there to [understand].

Thomas Martin from Sydney served on the HMAS Australia, a heavy cruiser. His job was to man a pom-pom gun, a large, multi-barreled weapon designed for anti-aircraft use, though Mr. Martin mentions at one point using it to fire at a U-boat that had come to the surface. He describes protecting his ship from incoming dive bombers.

Stukas make a screaming sound when they dive on you […] They also had bombs when they fall, make a screaming sound too when they come down. Stukas used to come in later on in formations of five and they fly around the ship. Now you watch these blokes and the one that dipped his wings would be the next Stuka to dive probably and he’d dive on you and dived down very low and go over the water away. Now having dropped his bomb you weren’t worried about him, you didn’t pay more attention to him, he was gone. But the next one would be on their way.

Another sailor who did a lot of convoy duty was Arnold Coleman from Towoomba, Queensland, and mentions formations of three, as well as noting the difference between German and Italian tactics.

At night time we had U-boats, at daytime we had the bombers, the Stukas. The Stukas were the worst, there used to be three of them and they used to circle over the top and they used to take it in turns to come down. They were playing fair dinkum the Germans, but the old dagos [Italians], they never bothered you, they used to bomb at about thirty five thousand feet, you had plenty of time because as soon as you saw the bomb leave you’d just flip and away you’d go.

Merchant Marine

As bad as protecting a convoy was, being on an almost defenceless merchant marine vessel was a lot worse. We have the recollections of one of them in the archive, Mr. Ware who went on multiple runs from Australia to Britain, with several shorter convoys within the Med as well.

Mr. Ware had lied about his age to get a spot on the ship and as a result was 15 when he first saw action, manning one of two Hotchkiss machine guns the ship was equipped with, its only armaments except for a heavy ship-to-ship gun.

According to himself, growing up on a farm had made Mr. Ware a crack shot, able to figure out where enemy aircraft were headed and allowing him to do some damage.

[…] when the air attack started […] my position was on the starboard Hotchkiss and I shared with another cadet there and we took it in turns to be the gun layer, firing it or keeping the ammunition strips which were metal hinged belts, supplied and see and when you were nearly out of, if you stopped firing and you weren’t out of ammunition on that belt you took it off and put a new one on. Then that was put aside and the job of the assistant, taking turns, was to replace the empty bullets with more bullets from the ammunition boxes so that you at all times had all of your spare ammunition was ready to use so even when you weren’t actually firing it, you were working so that you had full ammunition at all times.

There were tracers involved about every fourth bullet I think so you could follow the flight of your bullets up at the aircraft and you returned and I had that, I was used to it as a kid firing a BB gun when we’d flick a penny up and as to what you call aim off and in direction of the movement of the aircraft you had to anticipate where it was going to be by the time the bullet arrived.

Mr. Ware also describes the sensation of being under attack vividly:

We were attacked all day long from dawn till dark and it was summertime in the Mediterranean so you had darkness till eight o’clock at least at night and they’d come over in waves and it was and there was high level bombing parallel and there was medium level bombing and there was low level bombing and there was torpedo bombing and they were launching, they’d come in low and launch torpedoes at you and we had the Stukas, the dive bombers which had these sirens on them and they’d dive down at you and this scream […] it was terrifying sound as they were getting closer and closer but they were their tactics were to launch different types of attack at the same time.

The attacks weren’t just overwhelming to the senses; they were also effective. Mr. Ware says that the priority of the attackers was to first take out any carriers they could. Without planes, all the convoy could rely on was its ack-ack, which generally wasn’t nearly as effective.

Surviving an ambush

On one of his convoy trips, his ship came under attack this way forcing his convoy into the Skerki channel, the relatively shallow bit of sea between Sicily and Tunisia, relatively close to Malta.

[…] unknown to us there were 26 E-boats [German torpedo boats] waiting for us. They’re the very fast 50 knot motor torpedo boats and there was either three or four enemy submarines. They were Italian as it turned out and it was a minefield as well. […]The mines blew up when we cut them and the whole ship jumped out of the water and it started [to leak] in the engine room.

The convoy pushed on, however, but due to how shallow the channel was, the larger escorts, battleships and heavy cruisers, had to turn back. This made the merchant ships easy pickings for the E-boats. Several light cruisers did make it in, though, and tried to screen the remaining merchant ships while also picking up any survivors from ships that had been sunk by the Axis. In the chaos, suddenly a nearby British cruiser exploded, hit by the torpedo from an incoming E-boat.

Now the lookout said he saw this E boat coming at high speed and the Captain ordered harder port and then in seconds in came right down the starboard side of the ship and I couldn’t depress the muzzle of my Oerlikon gun to hit it cause it went past so fast so close I couldn’t point it down and so I swung it around and I was just about to fire and the second officer smacked me across the back of the head and he said “Don’t f’ing shoot,” he said “you’ll kill the gun crew aft”.

The attack was successful, and at least one more cruiser and an unknown number of merchant ships went down. Mr. Ware’s ship, however, somehow found itself ahead of the chaos, in open water with a straight shot to the escort ships that had to sail around the channel’s shallows, with Malta visible in the distance. As the ship limped over, however, enemy planes took it under fire, forcing them to abandon ship. A British destroyer came alongside and the crew jumped over, leaving their precious cargo behind.

The Malta Convoys

The hair-raising stories of the Australian veterans should give you an idea of the madness of the convoys, and the bravery of both the men that crewed the merchant ships and the navy vessels that protected them. Without their sacrifice, there’s no doubt Malta would have fallen to the Axis, breaking a vital supply line for the troops fighting in North Africa.

For more on Australians who fought the desert war, check out our article on the first battle at El Alamein or the Benghazi handicap.

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 165

1. The ‘Mulberry Harbours’ were an important part of which military operation?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.