Reading time: 31 minutes

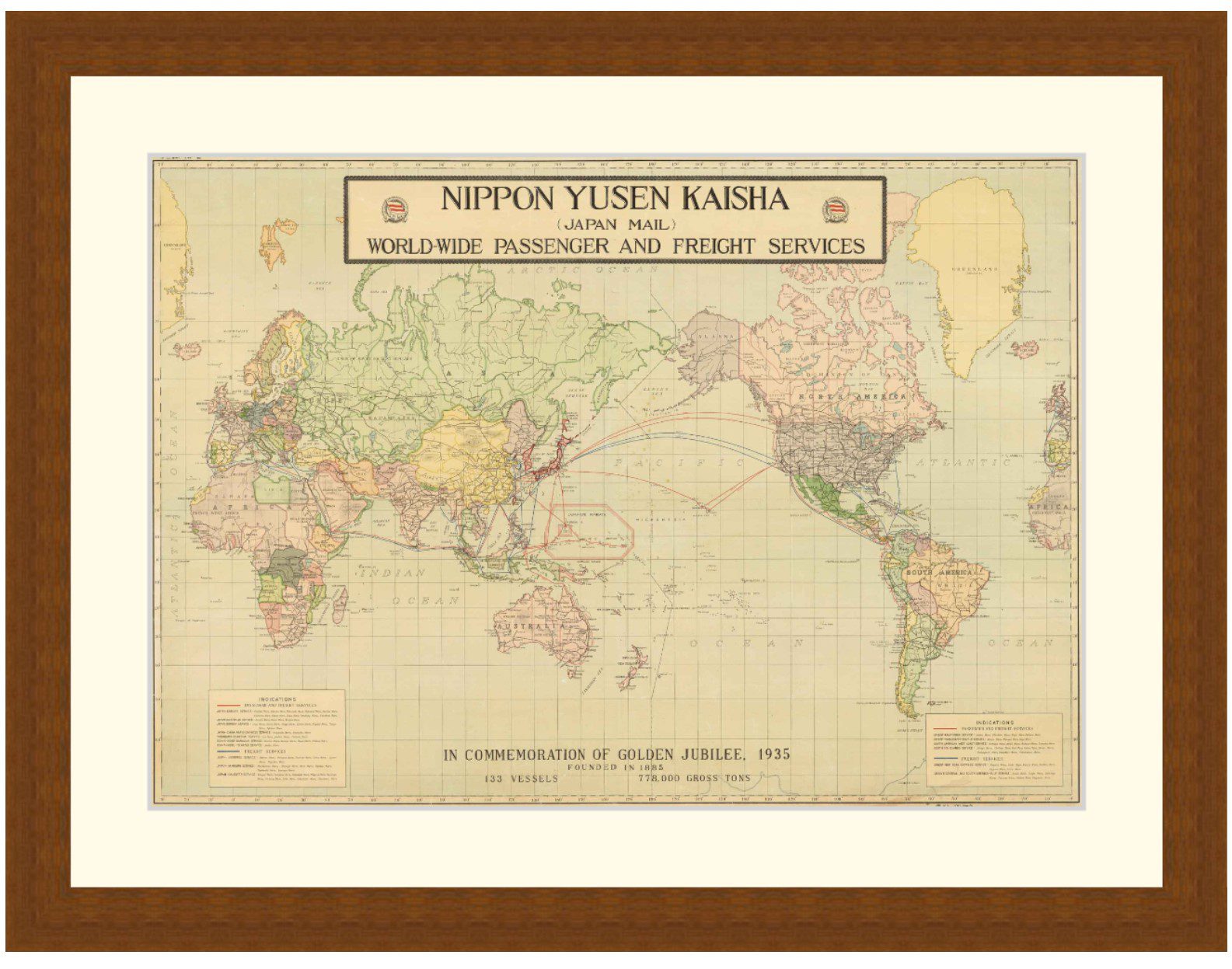

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition, 1911-1914, became the stuff of legend, one of the very best polar expeditions as it attempted to utilise modern technology far more than was previously attempted in Antarctica. Douglas Mawson (who was knighted for his achievements in 1914) became a household name in Australia, eventually appearing on the 1984 Australian $100 paper banknote, resplendant in his signature woolen polar balaclava.

By Dion Makowski

Douglas Mawson’s equipment for his 1911–14 Antarctic expedition was of the very latest. Everything was cutting-edge, from colour photography to the REP monoplane, which is the subject of this article. The expedition’s purpose, being to explore and chart the areas closest to Australia which they did with great success despite some terrible tribulations..

Mawson was in London through early 1911, ordering whatever he needed that could not be supplied from Australia. One of his closest friends was Kathleen Scott, whose husband (Robert Falcon Scott) was at that very time engaged in his own (fatal) South Polar expedition. Mawson had himself accompanied Sir Ernest Shakleton on his incomparable 1909 Antarctic expedition which provided the first team to reach the South Magnetic Pole. Her current passion was flight, in which she was well versed.

Mawson had been toying with the idea of an aeroplane—it could conceivably reconnoitre in advance of sledging journeys, and in the run-up to the voyage to Antarctica it would generate useful publicity, essential for this mainly privately-funded expedition. Even if not flown in Antarctica it could serve as an air-tractor hauling sledges. But what type of aeroplane? The science of flight was in its infancy. Everything was trial and error, and most types were still essentially prototypes, hand-built in small artisanal establishments. Biplanes were generally more stable and manoeuvrable but slower than monoplanes, which were at the cutting-edge of the new art—“state-of-the-art”, in fact.

Characteristics of the first Vickers Monoplanes

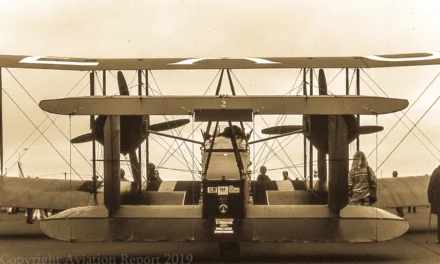

Similar to the Type D REP Monoplanes, these were shoulder-wing monoplanes carrying pilot and passenger in tandem. Fuselage construction was of steel tubing with welded and bolted tubular end-fittings at the joints, braced with piano wire and covered with fabric. Doping was done by any agent that would tighten up the fabric. Pilot control embodied the single control column and lateral control was by “wing warping”. No ailerons were fitted as such. The undercarriages had dual wooden skids and four wheels (two each side) sprung by elastic cord on a lever system at the top of the legs. Usually, Vickers-built, five-cylinder fan radials with air cooling were fitted, said to be of 60 hp each, maximum speed was around 56mph and the aircraft weighed about one thousand pounds empty. With a lower power to weight ratio and small margin between flying and stalling speeds, they were tricky to fly and lacked inherent stability, but they were very strong. Archibald Low’s original reconstruction included much strengthening, improved practices of welding, revising their steel-tube frames to reduce offsets at the joints and structurally stronger, Farman-influenced undercarriage as mentioned above. It was intended to employ steel spars (and dural ribs?) in the wings of later machines, in place of the wooden construction in the first monoplanes. Lieutenant Watkins was to accompany the machine to Australia and on to Antarctica to fly it there

Following its arrival at Port Adelaide, the REP was unloaded, unpacked and carefully assembled, test-flown by Watkins on 4 October 1911 at Adelaide’s Cheltenham Racecourse, and then flown again the following day, 5 October, during a fund-raising display at the same place, where it crashed.

Mawson decided to take the repaired machine to Antarctica without its wings. As a pilot was no longer required, Watkins returned to England. The machine’s maintenance would be in the hands of F H Bickerton FRGS, appointed to the expedition in England as engineer and motor expert.

The above includes extracts from Philip Ayres’: Mawson: A Life (Miegunyah Press/Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1999.

During the 1930s, de Havilland Aircraft Company Ltd. used creative renumbering of the first production DH94 Moth Minor airframe, c/n 94001 resulting from a crash during type spin trials. Moth Minor c/n 94006 became c/n 94001.

I have also come across a similar situation with regards to Douglas Mawson’s use of a Vickers-Pelterie R.E.P. type Tractor Monoplane in Antarctica in 1912. It appears similar actions occurred in both instances.

It was while I was researching this fascinating aeroplane, that I sighted the following references: “Vickers Aircraft since 1908” by C. F. Andrews (Putman, 1969) and “British Aviation: the Pioneer Years 1903-14” by Harold Penrose (Putman, 1967) – both copies were generously loaned by John Hopton.

According to Andrews, the first airframe was partly constructed of original Pelterie rear fuselage, obtained in France, and Vickers redesigned and built the rest of the structure. They were also said to have produced a French-built R.E.P. Monoplane for demonstration purposes. However, if we read Penrose, it seems likely that the first three Monoplanes were delivered from France, and while each retained the Pelterie rear fuselage, they had re-built Vickers two-seat forward fuselages. The French-built demonstrator may have been delivered to Vickers at this time.

Penrose then says the first monoplane was badly damage in a crash at Brooklands (Jul-Aug 1911), with Lieut. Hugh Watkins as passenger for a “sales flight” on behalf of Douglas Mawson, to whom Vickers had sold the second aircraft for his Australasian Antarctic Expedition (I believe this may actually have been a training flight for Watkins, pilot for the expedition). Capt. H. Wood of Vickers did not let it generally be known that the first R.E.P. had crashed, therefore No. 2 was quickly substituted and re-designated No. 1, and No. 3 Monoplane became No. 2 at the Vickers Flying School at Brooklands. This interesting comment hints at the existence of two classifications for these early Monoplanes. Historically, we can identify the individual airframes by the order of their construction; while Vickers appear to have numbered their aircraft for commercial purposes. Penrose refers to this as the “official” numbering of the aircraft. The result is, there must almost certainly have been three “Vickers – R.E.P.” type monoplanes built, with the fourth (being re-designated No. 3) therefore becoming the first entirely constructed at Erith by Vickers, to their own design – the redesigned Monoplane.

The third airframe (‘official” Vickers No. 2) was probably used at Brooklands, where the first Monoplane, if re-built after its crash, may also have gone. This may help explain why Andrews lists “No. 2” as later re-engined with a “Boucier” engine – this was very likely done to one of the airframes remaining in Britain. Indeed, this may even have been the power plant once installed in the French-built demonstrator aircraft.

The accepted theory, that Vickers had built a total of eight early Monoplanes of various configurations from 1911 (two “Vickers-R.E.P. types, Nos 3 to 8 being substantially redesigned) could be revised to nine such aeroplanes, given that Nos 1 to 3 were of Vickers modified R.E.P. standard, with Nos 4 to 9 being of later redesigned types (as described in both references). On the balance of probabilities, Vickers built nine airframes, but numbered them 1 to 8, having issued No. 1 twice!”

As further support to this idea, researchers have since claimed, that Mawson took the first Vickers-R.E.P. on his expedition. Penrose, through his contemporary aviation contacts, seems to have provided us with a vital clue. I have since spoken with Vickers researchers overseas; they can provide no further evidence from factory records to support these theories, However I have had a recent conversation with Dr Tony Stewart, who has been actively seeking the airframe of Mawson’s Air-tractor sledge who passed me these references from a French aviation historical magazine article; Les aéroplanes et moteurs R.E.P. by Gérard Hartmann.

Translations from page 17 about the air tractor:

“Transferred to the aviation (sic) Vickers department on March 28, 1911, Captain Herbert F. Wood flew the first monoplane manufactured at Barrow-in-Furness, the Vickers No. 1, at Dartford in Kent during the summer of 1911 in July.”

“The Vickers No. 1 (REP type B) is destroyed in a crash in 1911. The No. 2 is sold to Dr. Douglas Mawson; destined for the Australasian Antarctic Expedition of 1912, it was destroyed in October 1911 in Adelaide during a test after being transported by boat and its reassembly.” (the latter statement can be seen to be premature but as an airworthy entity, this REP no longer existed)

Clearly, there is no reference in these quotes to the subsequent use of Vickers 1 in Antarctica.

On 2 Dec 1911, S.Y. Aurora and the main party of the Australian Antarctic expedition sailed from Hobart for Macquarie Island and Antarctica. The wings of the monoplane apparently were relatively intact (repairable) but left behind in Australia. 19 Jan 1912, unloading at Cape Denison was completed and included was the air-tractor under the care of Bickerton. Accommodation, including a hangar for the air-tractor was constructed… (1)

On the western side of (the hut at Cape Denison); Commonwealth Bay: a makeshift shelter of packing cases, boards and canvas, called “the hangar” was erected in the Autumn (March-May) of 1912. This was to provide shelter for Bickerton to assemble his Vickers R.E.P. Monoplane.

(Source: State Library of Victoria: SLT919.89 M44 from Home of the blizzard, Vol.1)

15 Nov 1911, the first trial was made following modifications by Bickerton ‘to adapt it to local requirements’. The delay in conducting the trial was caused by continuous winds but several successful trips were made. A speed of 20 miles per hour was obtained up ice slopes of one in fifteen, in the face of a wind of fifteen miles per hour. 3 Dec 1912 an incident occurred: while towing four loaded sledges, the engine developed an internal disorder and next day, when being run, it suddenly stopped, breaking the propeller. Later, the air-tractor was returned to the hangar where the engine was found to have several pistons seized and broken. “Extreme cold had apparently solidified the lubricating oil and the engine seized, so the vehicle never served any useful purpose.” A year later, in Dec 1913, the damaged engine was loaded on Aurora and with the party, reached Adelaide on 26th February 1914. The following paragraphs describe these activities, and the outstanding results initially achieved, in detail.

Air-Tractors are great consumers of petrol of the highest quality. This demand, in addition to the requirements of two wireless plants and a motor-launch, made it necessary to take larger quantities (than) we liked of this dangerous cargo. Four thousand gallons of “Shell” benzine and 1,300 gallons of “Shell” kerosene, packed in the usual four-gallon export tins, were carried as deck cargo, monopolizing the whole of the poop-deck. (Vol.I p 24)

Returning to the fortunes of the air-tractor sledge, which was to start west early in December (1912: ed). Bickerton has a short story to tell, inadequate to the months of work which were expended on that converted aeroplane. Its career was mostly associated with misfortune, dating from a serious fall when in flight at Adelaide, through the southern voyage of the Aurora, buffeted by destructive seas, to a capacious snow shelter in Adelie Land – the Hangar – where for the greater part of the year it remained helpless and drift-bound. (Vol.II p.6)

Bickerton takes up the story (for 1912):

“I had always imagined that the air-tractor sledge would be most handicapped by the low temperature, but the wind was far more formidable. It is obvious that a machine which depends on the surrounding air for its medium of traction could not be tested in the winds of an Adelie Land winter. One might just as well try the capabilities of a small motor-launch in the rapids at Niagara. Consequently, we had to wait until the high summer. With hopes postponed to an indefinite future, another difficulty arose. As it was found that the wind would not allow the sea-ice to form, breaking up the floe as quickly as it appeared, the only remaining field for maneouvres was over the highlands to the south; under conditions quite different from those for which it was suited. We knew that for the first three miles there was a rise of some one thousand, four hundred feet, and in places the gradient was one in three and a half. I thought the machine would negotiate this, but it was obviously unsafe to make the venture without providing against a head long rush downhill, if, for any reason, power should fail.”

Note: This sequence was believed to feature expedition biologist, John George Hunter,but is most likely the Engineer, Bickerton (see bio note)

“Suggestions were not lacking, and after much consideration, the following device was adopted: A Hard rock-drill, somewhat over an inch in diameter, was turned up in the lathe, cut with one-eighth-inch pitched, square threads and pointed at the lower end. This actuated through an internal threaded brass bush held in an iron standard; the latter being bolted to the after-end of a runner over a hole bushed for the reception of the drill. Two sets of these were got ready; one for each runner. The standards were made from spare caps belonging to the wireless masts. The timely fracture of one of the vices supplied me with sufficient ready-cut thread of the required pitch for one brake. Cranked handles were fitted and the points, which came in contact with the ice, were hardened and tempered. When protruded to their fullest extent, the spikes extended four inches below the runner. The whole contrivance was not very elegant, but impressed one with its strength and reliability. To work the handles, two men had to sit one on each runner. As the latter were narrow and the available framework, by which to hold on and steady oneself, rather limited, the office of brakesman promised to be one with acrobatic possibilities.”

“To start the engine it was necessary to have a calm and, preferably, sunny day; the engine and oil-tank had been painted black to absorb the sun’s heat. On a windy day, with sun and an air temperature of 30 Degrees F, it was only with considerable difficulty that the engine could be turned – chiefly owing to the thickness of the lubricating oil. But on a clam day with the temperature lower – 20 Deg. F for example; the engine would swing well enough to permit starting, after an hour or two of steady sun. If there were no sun even in the absence of wind, starting would be out of the question, unless the atmospheric temperature were high or the engine were warmed with a blow lamp.”

“It was not till November 15 that the right combination of conditions came. That day was calm and sunny, and the engine needed no more stimulus than it would have received in a “decent” climate. Hannam, Whetter and I were the inhabitants of the hut at the time. Having ascertained that the oil and air pumps were working satisfactorily, we fitted the wheels and air-rudder, and made a number of satisfactory trials in the vicinity of the hut. The wheels were soon discarded as useless; reliance being placed on the long runners. Then the brakes were tested for the first time by driving for a short distance uphill to the south and glissading down the slope back to the hut. With a man in charge of each brake, the machine, when in full career down the slope, was soon brought to a standstill. The experiment was repeated from a higher position on the slope, with the same result. The machine was then taken above the steepest part of the slope (one in –three and a half) and, on slipping back, was brought to rest with care. The surface was hard, polished blue ice. The air rudder, by the way was efficient at speeds exceeding fifteen miles per hour.”

“On the 20th we had a clam morning, so Wetter and I set out for Aladdin’s Cave (at the top of the gradient extending to the ice-plateau; “At this spot the steepest grades of the ascent to the plateau were left behind, and it appeared to be a strategic point from which to extend our sledging efforts” – “a shelter beneath the ice”; Vol. I p194 ) …to depot twenty gallons of benzenes and six gallons of oil. The engine was not running well, one cylinder occasionally “missing”. But, in spite of this and a headwind of fifteen mph, we covered the distance between the one-mile and the two-mile flags in three minutes. This was on ice, and the gradient was about one in fifteen. We went no farther that day, and it was lucky that we did so, for, soon after our return to the hut, it was blowing more than sixty mph.”

“On Dec 2 Hodgeman joined us in a very successful trip to Aladdin’s Cave with nine 8-gallon tins of benzene on a sledge, weighing in all seven hundred pounds. After having such a good series of results with the machine, the start of the real journey was fixed for December 3. At 3pm it fell calm, and we left at 4pm, amid an inspiring demonstration of goodwill from the six other men. Arms were still waving violently as we crept nosily over the brow of the hill and the hut disappeared from sight. On the two steepest portions it was necessary to walk, but, these past, the machine went well with a load of 3 men and four hundred pounds, reaching Aladdin’s Cave in an hour by a route free of small crevasses, which I had discovered on the previous day. Here we loaded up with three 100-lbs food-bags, twelve gallons of oil (one hundred and thirty pounds), and seven hundred pounds of benzene. Altogether, there was enough fuel and lubrication oil to run the engine at full speed for twenty hours as well as full rations for three men for six weeks.”

“After a few minutes spent in disposing the loads, our procession of machine, four sledges (in tow) and 3 men moved off. The going was slow, too slow – about 3 miles on ice. This would probably mean no movement at all on snow which might soon be expected. But something was wrong. The cylinder which had been missing fire a few days before, but which had since been cleaned and put in order, was now missing fire again, and the speed, proportionately, had dropped too much.”

“I made sure that the oil was circulating, and cleaned the sparking-plug, but the trouble was not remedied. A careful examination showed no sufficient cause, so it was assumed to be internal. To undertake anything big was out of the question, so we dropped thirty-two gallons of benzene and a spare propeller. Another mile went by and we came to snow, where forty gallons of benzene, twelve gallons of oil and a sledge were abandoned. The speed was now six miles an hour and we did two miles in very bad form. As it was not 11pm and the wind was beginning to rise, we camped, feeling none too pleased with the first day’s results.”

“Whilst in the sleeping-bag I tried to think out some rapid way of discovering what was wrong with the engine. The only conclusion to which I could come was that it would be best to proceed to the cave at eleven and three-quarter miles – Cathedral Grotto – and there remove the faulty cylinder, if the weather seemed likely to be favourable; if it did not, to go on independently with our man-haul sledge.”

“On December 4 the wind was still blowing about twenty miles per hour when we set to work on the machine. I poured some oil straight into the crankcase to make sure that there was sufficient and we also tested and improved the ignition. At four o’clock the wind dropped, and in an hour, the engine was started. While moving along, the idle cylinder was ejecting oil, and this, together with the fact that it had no compression, made me hope that broken piston-rings were the source of the trouble. It would take only two hours to remove three cylinders, take one ring from each of the two sound ones for the faulty one, and all might yet be well!”

“These thoughts were brought to a sudden close by the engine, without any warning, pulling up with such a jerk that the propeller was smashed. On moving the latter, something fell into the oil in the crank-case and fizzled, while the propeller could only be swung through an angle of about 30 deg. We did not want to examine any further, but fixed up the man-hauling sledge, which had so far been carried by the air-tractor sledge, and cached all except absolute necessities.”

“We were sorry to leave the machine, though we had never dared to expect a great deal from it in the face of the unsuitable conditions found to prevail in Adelie Land. However, the present situation was disappointing.”

“Having stuffed up the exhaust pipes to keep out the drift, we turned out backs to the aero-sledge and made for the 11¾-mile cave, arriving there at 8pm. There was a cheering note from Bage in the “Grotto”, wishing us good luck.”

A party of four left the hut on the 20th (Jan, 1913), keeping a sharp lookout to the south-east for any signs of the missing party. (Mawson &c) They traveled as far as the air-tractor sledge which had been abandoned ten miles to the south bringing it back to the hut. (Vol.II p37)

On October 31 (1913) the good news was received that the Aurora would leave Australia on November 15. There were a great number of things to be packed, including the lathe, the motor and the dynamos, the air tractor engine (etc.) (Vol.II p 163)

Endnotes and attributions:

F. H. Bickerton F.R.G.S., 22 years of age, single, was born at Oxford, England. Had studied engineering, joined the expedition as electrical engineer and motor expert, a member of the main base party and leader of the western sledging party, he remained in (the) Antarctica for two years, during which time he was in charge of the air-tractor sledge, and was engineer to the wireless station. For a time during the second year, he was in complete charge of the wireless plant. (Vol.II p 283)

J. F. Hurley, 24 years of age, single, was of Sydney, NSW. He had been the recipient of many amateur and professional awards for photographic work before joining the expedition. At the main base he obtained excellent photographic and cinematographic records and was one of the three members of the southern sledging party. He was also present on the final cruise of the Aurora. (Vol.II p 285)

Dr Tony Stewart and Dr Chris Henderson

Mawson’s Huts Foundation

The site of Mawson’s Huts at Cape Denison in Commonwealth Bay is recognised under the Antarctic Treaty as a Historic Site & Monument. It has been declared an Antarctic Specially Protected Area and included in the Australian National Heritage List. Because of its significance, expeditions to protect and conserve the site have been undertaken by the Australian government (through the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) since the late 1970s) and the private non-profit conservation organisation the Mawson’s Huts Foundation (MHF) since 1997.

The Last Images

The AAD photographer Bob Reeves documented the position of the airframe in 1976. His photograph shows all but 500mm of the frame buried in the ice, and also displays the very low levels of ice around the huts. In February 1977 Bill Young and Dick Lightfoot visited Cape Denison briefly and later reported by telex from the Thala Dan that the frame was not visible and presumably had been blown into Boat Harbour. No expedition since then has seen the frame and the general belief has been that it was destroyed in the extreme weather of the site. Investigations over the last few years have challenged that view.

Did the airframe blow out to sea or sink into the ice? Cape Denison is the windiest place on earth, but despite this the frame remained in the same place for 60 years. Its feet are firmly anchored in the ice, and the last known photo showed it had sunk into the ice, rather than moved over it. This makes any contribution from the wind very unlikely. Evidence gathered over three expeditions gives weight to the conclusion that the air tractor frame has survived and is waiting to be exposed.

2007 Expedition

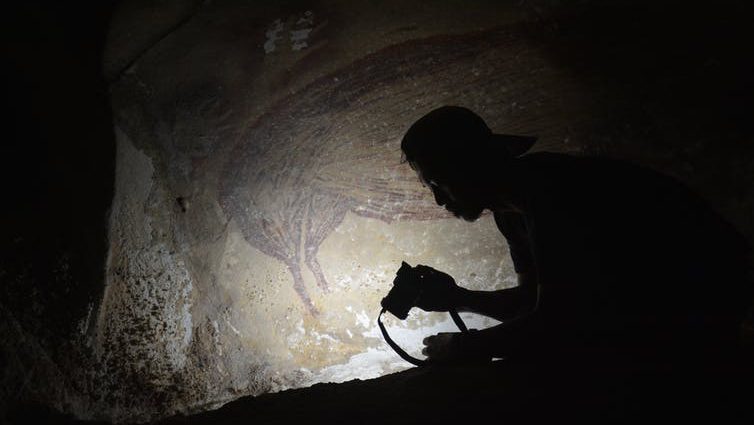

During preparations in 2007 the MHF expedition doctor, Tony Stewart, became interested in the fate of Mawson’s Air Tractor – the Vickers REP monoplane used by the 1911-14 Australasian Antarctic Expedition. As a pilot and owner of an ERCO 415-D Ercoupe (VH-ERC), he has a keen interest in aviation history. Searching for one of the early Vickers aeroplanes, and the very first aircraft to be taken to Antarctica captured his imagination, time, enthusiasm and energy for the next three years. Prepared with all the images and documents he could find relating to the Air Tractor, Tony set about determining the location of the fuselage from each photo. What quickly became apparent was that the frame of the air tractor had remained frozen in the ice in much the same position for more than 60 years, on the shore of Boat Harbour where the AAE left it in 1913, until the last known image in 1976. Rather than being blown out to sea as most people believed, it seemed likely that the frame had sunk deeper into the ice in more recent times, and was sitting safely below our feet.

The expedition’s archeologist Dr Anne McConnell located the third seat of the air tractor on Penguin Knob, on the northeastern side of Boat Harbour. The seat was not part of the original design and had been added in 1912 so a three-man team could ride together. Images from 1931 clearly show that the seat had been removed by that time. With no suitable tools to investigate further and no time or permission to conduct a dig, the search was put on hold until the next summer’s expedition.

2008 Expedition

In 2008, Dr Chris Henderson travelled south with the MHF team as the team doctor and to continue the search for the Air Tractor. With his background as a scientist, engineer and builder of ingenious gadgets he was able to gather encouraging evidence. Chris studied the continuous temperature records from the French station Dumont d’Urville (200 km away) and found there was an unusual period of high summer temperatures in the years 1976 and 1981. Comparison between Cape Denison and Dumont d’Urville data showed the temperature could be up to 10 degrees higher at Cape Denison.

Mawson’s reports indicate that the landscape can change very quickly in above zero conditions. This was confirmed during the 2001 Mawson’s Huts Expedition, and again was our experience in 2009-10. It only took 3 or 4 days of continuous above zero temperature and heavy rain for the surface ice near the harbour to turn to slush. The evidence from the Dumont D’Urville temperature records indicates that in both 1976 and 1981 the temperature stayed high for about six weeks, long enough for a substantial melting of the ice which would have allowed the frame to sink down to bedrock. Using ice-penetrating radar, combined with triangulation from historic images, the team located several likely sites in a small area northwest of the Huts. They had time for a dig at one of the locations of interest but found only seaweed on the rocky bottom of the ice-covered harbour shore. The seaweed confirmed that the area had been clear of ice at some point. The dig turned up nothing else, but at least the team was able to exclude one site from the list of places to look!

2009 Expedition

In 2009 both Tony and Chris combined efforts and returned to Cape Denison, Chris as the engineer to complete a number of projects and Tony as the team’s leader and doctor. To accurately estimate the position of the air tractor, we reviewed 3 key historical photographs. Careful study of the pictures enabled three transits to be drawn, which crossed at one point on the ice. We are confident that this is where the frame rested for 60 years before disappearing. We made a scan of that area using a magnetometer, looking for magnetic anomalies consistent with the all-metal frame. There is a large amount of artifact scatter between the huts and Boat Harbour which complicated this activity. For example, the AAD laid lengths of wire to act as a groundplane for the radio equipment. However there was a clear signal indicating a linear structure of about 6 metres, just to the west of the 2008 dig.

We then used ice-penetrating radar to map the bedrock at this site. To complete the picture of the terrain below the ice and harbor, we used differential GPS to accurately map the height of the ice, bathymetry equipment to map the harbour floor, an underwater camera to look for debris and drilled about 200 holes with ice augers to map the rock levels in the search area. Combining all the information clearly shows that the flat bottom of the harbor extends under the air tractor site. The fact that the terrain is not steeply sloped at this point adds weight to the argument that the frame would not slide seaward in a melt year. Unlike the plateau ice above and on either side of the Cape Denison area (which is constantly moving), there are no features of moving ice in the vicinity of the air tractor’s resting place. Discussion with glaciologists confirmed what Mawson said – the ice at Cape Denison is stationary. Therefore the airframe did not slide into the sea on moving ice.

The coil of a pulse induction metal detector was put down each of the ice auger holes to check for ferrous metal. We found that the only place with positive readings was the spot where we previously determined the frame sank. The ice auger also brought up a small piece of corroded wire from this area.

On New Year’s Day 2010 the tide was extraordinarily low, and Mark Farrell, one the expedition’s heritage carpenters, was walking around the sea edge near the search area. He found four connecting pieces, about 100 mm in size each. These turned out to be from the tail section, which was removed during Frank Bickerton’s experiments in 1912 with alternative steering devices (one of which, a metal rudder, is on display at the library at the Australian Antarctic Division in Kingston, Tasmania). This find shows that the frame, or parts of it, can survive for nearly 100 years in this harsh marine environment. This gives us further hope that when the next expedition digs for the frame, there will be something to find.

2010 expedition

The activities of the 2010 expedition were drastically reduced following the tragic fatal helicopter accident at the French base Dumont D’Urville. No dig was possible, however the conservation team did bring the fabric covered vertical stabilizer back to Australia for preservation. It had remained inside the workshop along with various spare parts such as metal tubing and cast metal joints.

Putting it all together

This search has taken many person-months of preparation, with help from many interested parties, including the Australian Antarctic Division, and a physical search on three consecutive expeditions. We are now in a position to make some comments, all of which point to the likely location of the frame:

- The harbour bottom is a shallow and flat, sloping gently under the ice where the plane sank.

- The ice in the search area is three metres deep and shows evidence of a substantial melt in the past.

- The discarded tail sections survived underwater until present.

- There is only one place where we found metal, and both magnetometry and ice-penetrating radar show an anomaly in this area.

- The same area coincides perfectly with historical images.

In conclusion it is most unlikely that the frame moved toward the harbour – either by wind or by ice. It seems almost certain it sank down into the ice, where it remained – at least until 1981 or thereabouts when it might have been exposed by a big melt. Our findings indicate there is some metal under the ice, and our radar shows an anomaly. Naturally we don’t know what it is; it may be the frame or it might only be a fragment of the frame. But we know there is something there and have many good reasons to believe it’s the Vickers REP. Digging a 3m hole in 3m deep ice took us two days, and we expect another dig will take a similar time. When resources are available the Mawson’s Huts Foundation intends to investigate further.

(Australian Antarctic Division – Australian Antarctic Magazine)

The search for Mawson’s Air Tractor continues……

Reproduced with strict permission, and much appreciation, from the original article printed in Aviation Heritage, AHSA, Vol.42 No.4, December 2011

Podcasts about the Mawson Expedition

Articles you may also like

Australian pilots in the fight for control over the Mediterranean

Reading time: 11 minutes

The Siege of Malta, a two-year ordeal of bombs, heat and dust, was one of the most important battles of the Mediterranean theatre in World War Two. Few of the victories in North Africa and Italy would have been possible had the island fallen to the Axis. In this article, we let Australian pilots who defended Malta tell their stories.

Australia’s first known female voter, the famous Mrs Fanny Finch

Reading time: 7 minutes

On 22 January 1856, an extraordinary event in Australia’s history occurred. It is not part of our collective national identity, nor has it been mythologised over the decades through song, dance, or poetry. It doesn’t even have a hashtag. But on this day in the thriving gold rush town of Castlemaine, two women took to the polls and cast their votes in a democratic election.

This article is published with the permission The Aviation Report.