Reading time: 9 minutes

For three long years, as Britain and her allies first clung to survival and then clawed victory out of the face of overwhelming odds, a single island held out hope in the Mediterranean. Malta, just 17 miles long and 9 miles wide, with its neighboring island of Gozo had long stood as a fortress in the sea for whoever could hold it. Over the centuries, Malta had withstood Moorish, Turkish, and French sieges and fallen under a variety of civilisations dating back thousands of years.

By Morgan WR Dunn

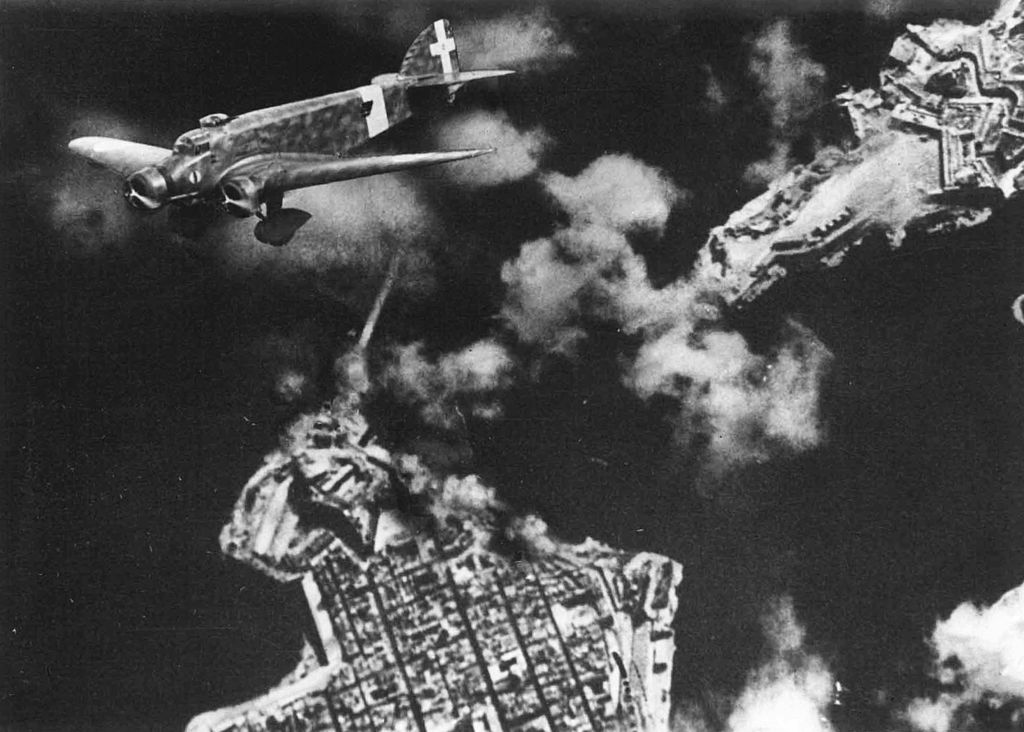

But in 1940, it faced its most daunting foe yet when the modern air and naval forces of Italy and Nazi Germany combined to threaten Britain’s critical toehold. Over three years, more than 3,000 raids were launched against the island as the sea around it raged. But thanks to a stubborn British wartime government, endless resourcefulness, and the efforts of thousands of Allied pilots and ground crews from Australia and around the world, the little island weathered the storm.

FORTRESS MALTA

When the first young Australian flyers set foot on Malta in 1942, the crowded, ancient island had been under siege from the skies for a year and a half. The defense had started as a desperate affair, with only three crude airstrips and a few Gloster Sea Gladiator fighters abandoned by the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious to fend off Italy’s Regia Aeronautica.

At first, the odds were impossible: the Italians had spent the 1930s stockpiling experience in aerial combat and horrific bombing campaigns in Spain and Ethiopia, while their German allies had built up one of the most advanced air forces in the world from scratch. What’s more, German forces were rampaging across North Africa, turning the tide in Hitler’s favor after Mussolini’s army had come close to destruction by a determined British resistance.

When the war broke out, London had long since written off Malta. It was too small, too close to Italian air and sea bases, dry, dependent on shipping for food, and dangerously under-armed. Only a few dozen anti-aircraft guns protected the main island and its smaller sister, Gozo. There was almost nowhere suitable for airfields, and the handful of smaller Royal Navy ships there couldn’t hope to hold off the combined weight of Italy’s fleet.

But when Winston Churchill ascended to the prime ministership, ushering in the wartime cabinet, that all changed. Small, inhospitable, poor, crowded, and exposed it might be, but the new wartime government realised, as countless nations had over the centuries, that Malta – just 60 miles from Sicily and square in the path from Axis territory to North Africa – had immense strategic value. Moreover, Britain’s new leader knew the empire had to make a stand.

“If we could get out of this jam by giving up Malta and Gibraltar and some African colonies,” Churchill said in a May 1940 Cabinet meeting, “I would jump at it. But the only safe way is to convince Hitler that he cannot beat us.”

ENTER AUSTRALIA

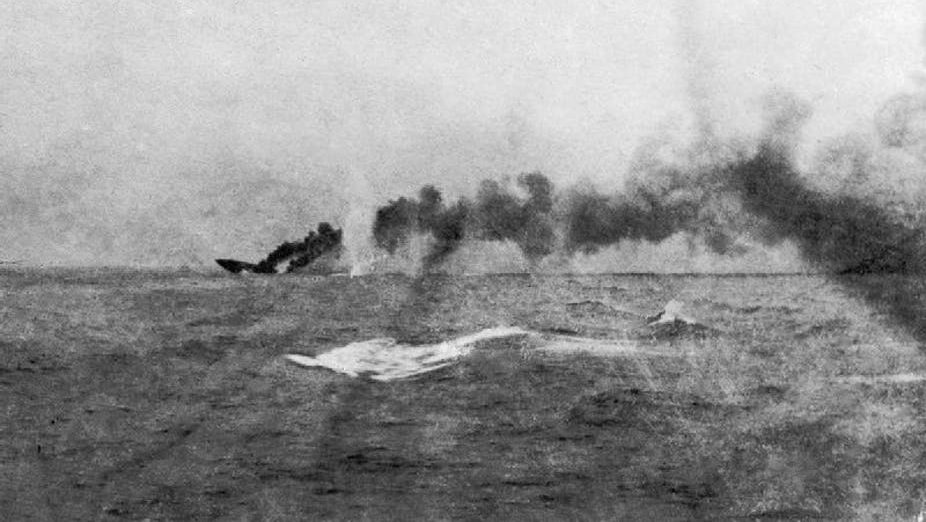

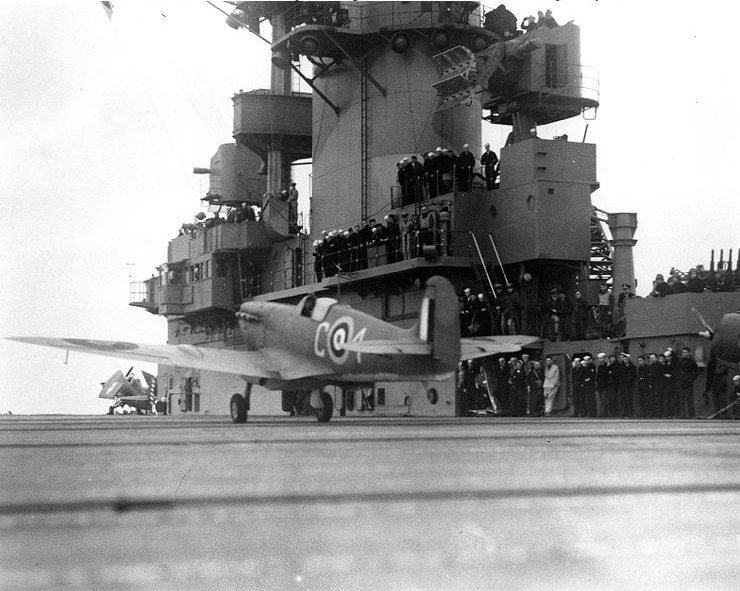

Malta, it was decided, was defensible — it had to be. And from then on, even as the many small victories which tipped the balance were being clawed out around the Mediterranean, into its center poured everything Britain could spare. Supplying the island with planes became a task for aircraft carriers: pilots aboard the outdated HMS Argus and HMS Eagle mastered the trick of seaborne launches to deliver such aircraft as Supermarine Spitfires, Hawker Hurricanes, and Bristol Blenheims and Beaufighters.

Most critically, Malta received radar. By mid-July 1941, four radar stations had been planted on the island, giving its defenders a badly-needed edge in outwitting Italian and German raiders. Walter Preen, a sailor then serving on the corvette HMAS Gawler, explained that

“Even in the Battle of Britain time, they gave Malta priority with radar, so their radar could pick up the raiders’ planes coming quicker than the English could pick them up coming from France.”

Even after the taps were opened up for Malta, though, scarcity was the norm. Everything, from planes to spare parts, had to be rationed and patched every day to keep the island fighting. Ground crews repaired bullet holes in fuselages with canvas and cardboard, and pens for the aircraft were constructed with empty fuel tins and chunks of the local limestone.

But Malta did have one thing in abundance: pilots. Following the success of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, the Royal Air Force was astonishingly cosmopolitan, with ground crews and aircrew from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States, Rhodesia, and elsewhere making up the island’s defenders from late 1942 onward.

They were just in time. Malta, at the intersection of Axis supply, trading, and communication lines, could not be allowed to fall. As RAAF pilot Kenneth Baird put it years later, “They had to keep it open because it was right in the middle of the Mediterranean surrounded completely and yet if we lost that we were gone. We’d have lost North Africa, possibly Syria, Iraq and all that oil area could have gone.”

WARTIME LIFE ON MALTA

Australians came to Malta either by sea or by planes they were flying to North Africa, Crete, or the Middle East beyond. Many stayed on the island not by choice, but because local air units developed a habit of commandeering newer aircraft. Since North Africa was by then threatened by Germany’s Afrika Korps (and to a much lesser extent by remaining Italian forces), Malta was needed as both air defense station and safe harbor for supplies heading across the Mediterranean.

Pilots assigned, or waylaid, there had nothing to do but wait for days on end until their turn on the flying rota came. According to Clarence “Des” Singe, a Queenslander who flew with 104 and 458 Squadrons, remembered that the food either “wasn’t too flash,” or was “pretty basic. You could buy an egg occasionally,” as Wellington bomber pilot Keith Cousins recalled. Pilot Bob Cock was blunt: “The food was bad.” And aside from the cinema and a small number of local bars in Valletta, Malta offered very little for the newcomers to do. Before long, most pilots were itching to get in the air to relieve the boredom.

RAAF PILOTS IN FLIGHT

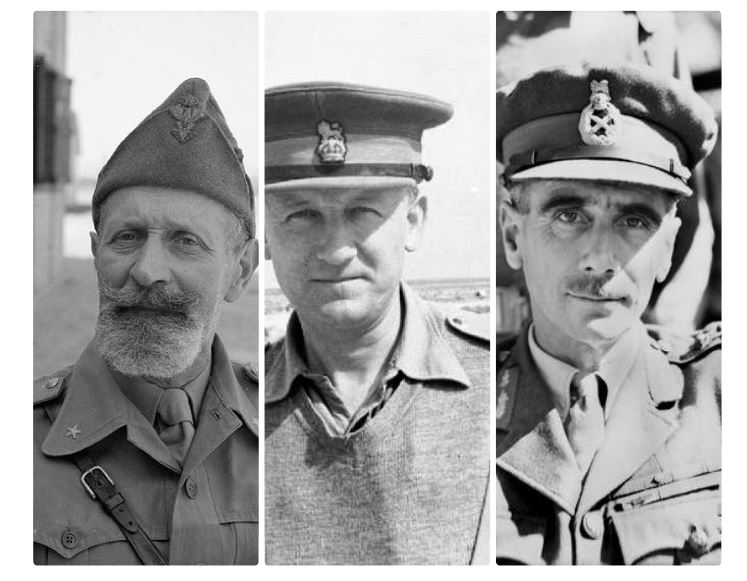

When they were airborne, however, the Australians shone. One of the RAF’s outstanding aces on Malta was Virgil Paul Brennan of No. 249 Squadron. Between March and July 1942, Brennan shot down 10 Axis aircraft, including a Messerschmitt Bf 109 while flying an outclassed Hurricane. He received the Distinguished Flying Medal for the feat.

John “Slim” Yarra, who flew Spitfires with No. 185 Squadron, shot down at least as many, including Bf 109s and several Junkers Ju 88 bombers. John “Tony” Livingstone Boyd, Yarra’s fellow Queenslander, also shot down several of the more than 500 aerial losses the Axis forces suffered.

As boring as the posting could be, all were in exceptional danger. Des Singe remembered that “the Germans were in Sardinia, and Sicily, and they were so close to us we could hear the engines running up when they were taking off. We knew when we were going to get raided because you could hear them taking off.”

And as brave as they were, many died. Boyd was shot down and killed in May 1942, and many were listed as missing when they were downed over the ocean. Air-sea rescue forces on the island were kept hard at work, and were much appreciated by the pilots. Jack Doyle recalled a fellow fighter pilot claiming that “the air-sea rescue was so efficient, you never got wet above the waist.” Both Yarra and Brennan, like many others, would die in other theaters of the war after surviving the inferno of Malta.

MALTA SOLDIERS ON

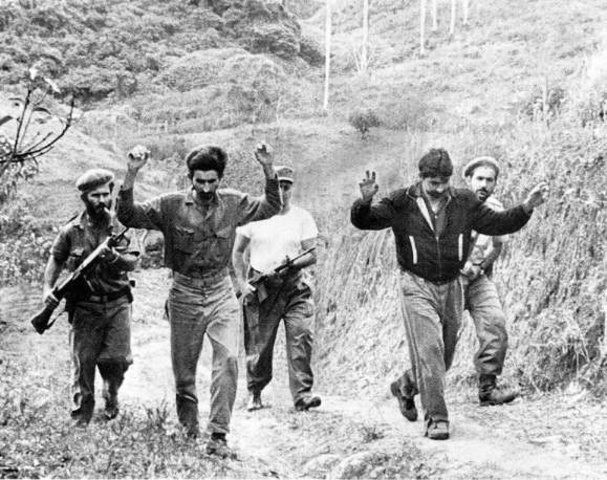

The Siege of Malta was lifted in October 1942, when German Air Force commander Albert Kesselring admitted his forces couldn’t shift the stubborn defenders. The Italian and German attackers had paid dearly, over 17,000 had been killed, 2,300 Axis merchant ships had been sunk, the Italian Navy’s transport capacity was crushed, and most importantly, they’d failed to support their forces in North Africa. Malta had not just weathered the storm: it had conquered it.

In 1943, immense pressure was lifted from the island when Italy surrendered and the Axis were crushed in North Africa. Throughout the remainder of the war, the island served as a vital Allied air and sea base, and many other Australians would serve there.

Many of the veterans would recall that it wasn’t just they who’d suffered: Des Singe said that “it was mainly the people of Malta that suffered because they didn’t have any food supplies for eight months. That is an awful long time for an island to go without food. We used to give them some of our Red Cross parcels.” “The Maltese were starving, they really were,” said Bob Cock. “And everybody lived underground. The limestone – you could carve it out like cheese, but it drips water all the time.”

In recognition of their perseverance, in April 1942 King George VI awarded the George Cross to the entire Maltese people. When it finally reached the island on 15 August, it fell to Australian pilots like Russell Baird of 461 Squadron to escort the ships carrying the award into Valletta’s Grand Harbour. The Maltese, he recalled, had also struck a George Cross and awarded one to him that day. “I don’t know what for!” he said in 2003. “Just because I did what my job was, I suppose.”

Podcasts about Australians in the Mediterranean during WWII

Articles you may also like

History’s Greatest Nicknames

Reading time: 7 minutes

A browse through any military history book will no doubt bring up titles of famous officers, often bearing unusual, surprising, or sometimes downright hilarious nicknames. In many cases, it’s clear where the sobriquet originated, while other examples hold a less-obvious significance.

The Confessions of Nat Turner, The Leader of the Late Insurrection in Southampton VA – Audiobook

By Thomas R. Gray THE CONFESSIONS OF NAT TURNER, THE LEADER OF THE LATE INSURRECTION IN SOUTHAMPTON VA – AUDIOBOOK This is a detailed description of the massacre that took place on August 21-23, 1831 that became known as Nat Turner’s Rebellion. Nat Turner himself relates the events to the author from his jail cell […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.