Reading time: 6 minutes

Each year the holidays bring with them an increase in both the consumption of alcohol and concern about drinking’s harmful effects.

Alcohol abuse is no laughing matter, but is it sinful to drink and make merry, moderately and responsibly, during a holy season or at any other time?

By Michael Foley, Baylor University

As a historical theologian, I researched the role that pious Christians played in developing and producing alcohol. What I discovered was an astonishing history.

Religious orders and wine-making

Wine was invented 6,000 years before the birth of Christ, but it was monks who largely preserved viniculture in Europe. Religious orders such as the Benedictines and Jesuits became expert winemakers. They stopped only because their lands were confiscated in the 18th and 19th centuries by anti-Catholic governments such as the French Revolution’s Constituent Assembly and Germany’s Second Reich.

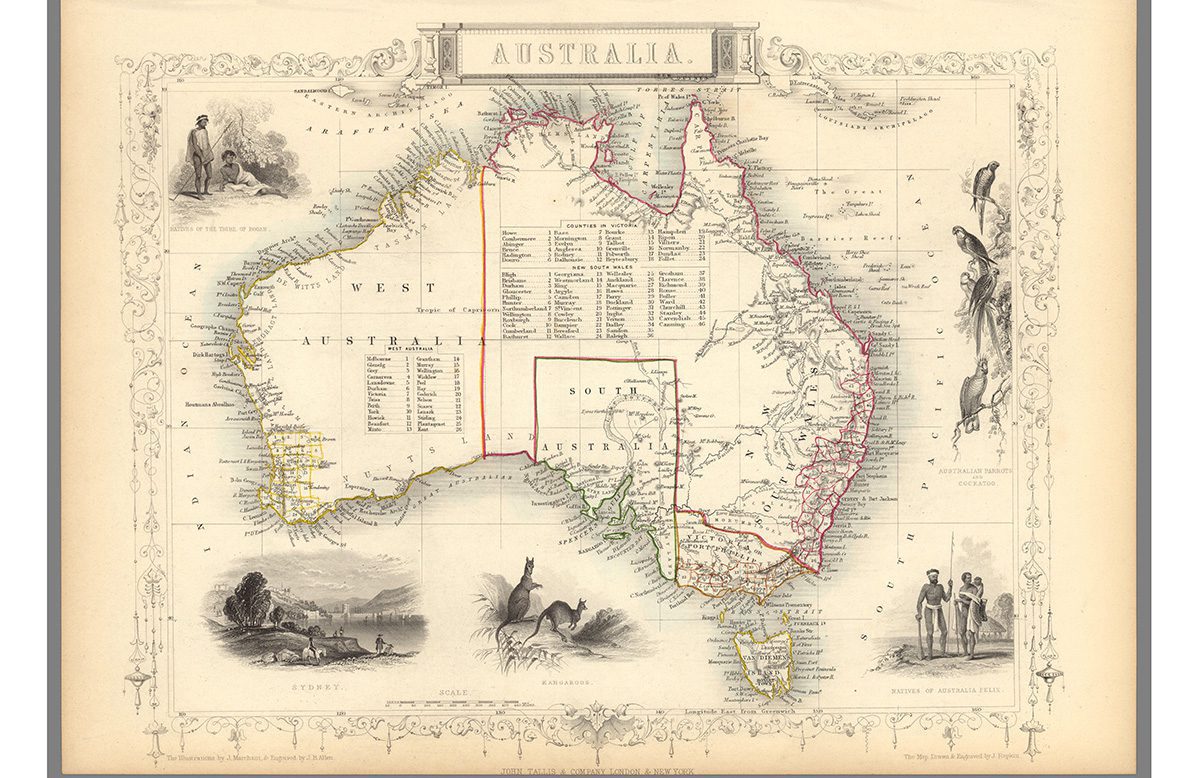

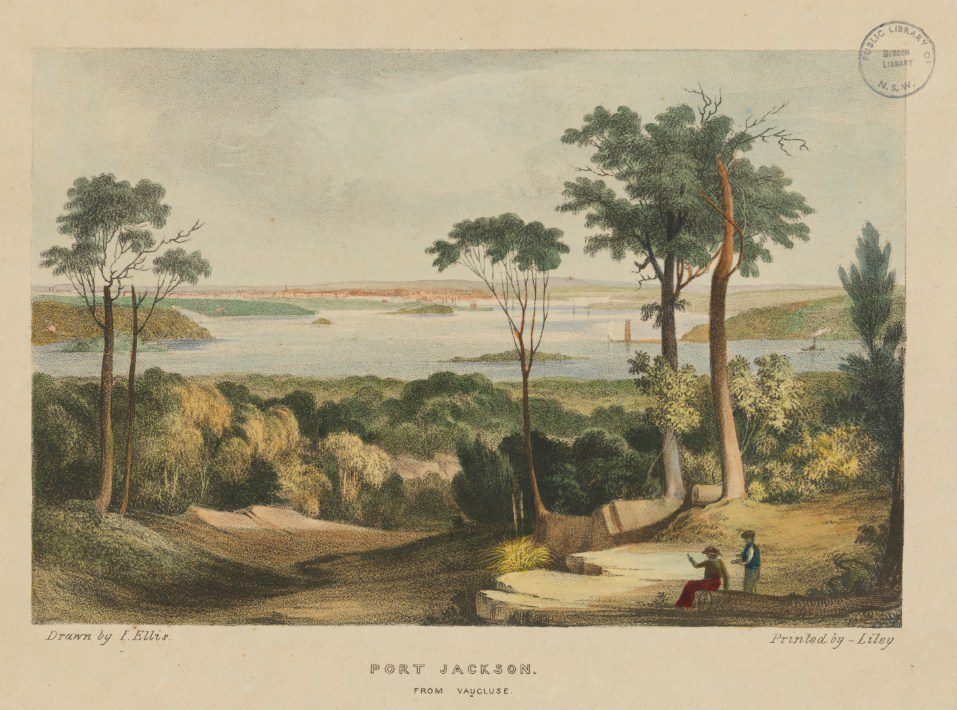

In order to celebrate the Eucharist, which requires the use of bread and wine, Catholic missionaries brought their knowledge of vine-growing with them to the New World. Wine grapes were first introduced to Alta California in 1779 by Saint Junipero Serra and his Franciscan brethren, laying the foundation for the California wine industry. A similar pattern emerged in Argentina, Chile and Australia.

Godly men not only preserved and promulgated oenology, or the study of wines; they also advanced it. One of the pioneers in the “méthode champenoise,” or the “traditional method” of making sparkling wine, was a Benedictine monk whose name now adorns one of the world’s finest champagnes: Dom Pérignon. According to a later legend, when he sampled his first batch in 1715, Pérignon cried out to his fellow monks:

“Brothers, come quickly. I am drinking stars!”

Monks and priests also found new uses for the grape. The Jesuits are credited with improving the process for making grappa in Italy and pisco in South America, both of which are grape brandies.

Beer in the cloister

And although beer may have been invented by the ancient Babylonians, it was perfected by the medieval monasteries that gave us brewing as we know it today. The oldest drawings of a modern brewery are from the Monastery of Saint Gall in Switzerland. The plans, which date back to A.D. 820, show three breweries – one for guests of the monastery, one for pilgrims and the poor, and one for the monks themselves.

One saint, Arnold of Soissons, who lived in the 11th century, has even been credited with inventing the filtration process. To this day and despite the proliferation of many outstanding microbreweries, the world’s finest beer is arguably still made within the cloister – specifically, within the cloister of a Trappist monastery.

Liquors and liqueurs

Equally impressive is the religious contribution to distilled spirits. Whiskey was invented by medieval Irish monks, who probably shared their knowledge with the Scots during their missions.

Chartreuse is widely considered the world’s best liqueur because of its extraordinary spectrum of distinct flavors and even medicinal benefits. Perfected by the Carthusian order almost 300 years ago, the recipe is known by only two monks at a time. The herbal liqueur Bénédictine D.O.M. is reputed to have been invented in 1510 by an Italian Benedictine named Dom Bernardo Vincelli to fortify and restore weary monks. And the cherry brandy known as Maraska liqueur was invented by Dominican apothecaries in the early 16th century.

Nor was ingenuity in alcohol a male-only domain. Carmelite sisters once produced an extract called “Carmelite water” that was used as a herbal tonic. The nuns no longer make this elixir, but another concoction of the convent survived and went on to become one of Mexico’s most popular holiday liqueurs – Rompope.

Made from vanilla, milk and eggs, Rompope was invented by Clarist nuns from the Spanish colonial city of Puebla, located southeast of Mexico City. According to one account, the nuns used egg whites to give the sacred art in their chapel a protective coating. Not wishing the leftover yolks to go to waste, they developed the recipe for this festive refreshment.

Health and community

So why such an impressive record of alcoholic creativity among the religious? I believe there are two underlying reasons.

First, the conditions were right for it. Monastic communities and similar religious orders possessed all of the qualities necessary for producing fine alcoholic beverages. They had vast tracts of land for planting grapes or barley, a long institutional memory through which special knowledge could be handed down and perfected, a facility for teamwork and a commitment to excellence in even the smallest of chores as a means of glorifying God.

Second, it is easy to forget in our current age that for much of human history, alcohol was instrumental in promoting health. Water sources often carried dangerous pathogens, and so small amounts of alcohol would be mixed with water to kill the germs therein.

Roman soldiers, for example, were given a daily allowance of wine, not in order to get drunk but to purify whatever water they found on campaign. And two bishops, Saint Arnulf of Metz and Saint Arnold of Soissons, are credited with saving hundreds from a plague because they admonished their flock to drink beer instead of water. Whiskey, herbal liqueurs and even bitters were likewise invented for medicinal reasons.

And if beer can save souls from pestilence, no wonder the Church has a special blessing for it that begins:

“O Lord, bless this creature beer, which by Your kindness and power has been produced from kernels of grain, and may it be a health-giving drink for mankind.”

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about the history of monks and alcohol

Articles you may also like

Finding ‘Forgotten’ Allies

Reading time: 8 minutes

Although it is difficult to calculate exactly how many Burmese personnel were recruited by SOE for operations within the country, we do know that it was in excess of 20,000. Those personnel represented at least fourteen different ethnic communities, from the majority Burman (Bamar) and well known Shan, Karen, Kachin, Chin, and Arakanese (Rakhine) peoples, to the less heard about Palaung, Kuki, and Lahu. Also included were nationalities who had large populations in Burma, such as the Gurkhas, Indians, and Chinese. Add to this the Anglo-Burman, Indo-Burman and other mixed ethnicity personnel, for example Shan-Kadu, and it is clear that there was a huge contribution made to Force 136 operations by non-Caucasian peoples. As my research for the Men of SOE Burma page has revealed, finding out about Asian Special Forces personnel in Second World War Burma has many obstacles.

Under what conditions are international sanctions effective?

Reading time: 7 minutes

According to US government data, 32 sanctions regimes are currently in effect. Canada, for its part, currently imposes sanctions on 20 different states and on terrorist groups such as Al Qaeda. The EU is currently implementing sanctions against some 30 countries and international actors. As for the United Nations, since 1966, the Security Council has put in place 30 sanctions regimes, from apartheid South Africa to Gaddafi’s (and according to him) Libya, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and the Islamic Republic of Iran.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.